One way to help solve the migration policy gridlock in the U.S. and other rich countries is to expand legal channels for poor people from developing countries to work temporarily at low skill jobs, according to a new book from CGD.

"The gains to people in poor countries from labor mobility are enormous compared to everything else on the development agenda," says Lant Pritchett, the author of the new book, Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility.

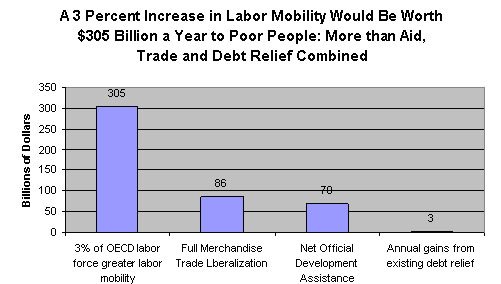

Pritchett cites estimates that if rich countries were to permit a mere 3 percent increase in the size of their labor force by easing restrictions on labor mobility, the benefits to citizens of poor countries would be $305 billion a year--almost twice the combined annual benefits of full trade liberalization ($86 billion); foreign aid ($70 billion) and debt relief (about $3 billion in annual debt service savings).

"Both rich and poor countries benefit when rich economies admit low-skilled workers," asserts Pritchett. In Hong Kong and Singapore, for example, foreigners working as housekeepers and nannies account for 7 percent of the labor force (compared to only 0.3 percent in the U.S.). These temporary household workers make it possible for more highly skilled women to work outside the home, raising national income by between 1.3 and 3.3 percent, and increasing tax revenues from the additional employment.

Globally, because of such benefits, a 3 percent increase in rich country labor forces through legal, temporary labor would result in a net annual gain of $56 billion to current rich country residents, on top of the $305 billion annual direct gain to migrant workers themselves and their families.

"Everybody knows that trade, aid and debt relief are development issues," says CGD president Nancy Birdsall. "Labor mobility is like the 800-pound gorilla in the room that nobody wants to discuss. Lant's book will change that."

The book is the latest publication from CGD's Migration and Development initiative, which aims to put migration at the center of the development policy agenda, and to bring solid evidence about the development impact of labor mobility to the rich world migration policy debate.

"Much of the research on migration and development has focused on remittances but most of the impact on sending countries lies elsewhere and is poorly understood," says CGD research fellow Michael Clemens, who coordinates the initiative. Clemens recently published a new dataset on Health Professional Emigration from Africa, as part of his study of the impact of the exodus of sub-Saharan nurses and doctors on health in the region.

A previous CGD book on migration, Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World, by Devesh Kapur and John McHale, examined the impact of skilled migration from developing countries and suggested ways to make such movements more supportive of development.

The temporary legal worker program that Pritchett proposes would focus on temporary, low-skilled labor and would separate labor mobility for such workers from the debate over migration and citizenship. It has two particularly innovative components:

- Labor-sending countries take responsibility for ensuring that temporary workers actually return home.

- Rich countries take responsibility for certifying labor shortages in specific industries.

Pritchett argues that these steps would help to address popular anxieties about migration, for example, that foreign workers will strain government budgets and steal jobs.

A key element in his proposed package is to ensure that temporary workers really return home when their stay is over. One way to do this, he says, is to reduce the sending country's future quota by one worker for each worker who fails to return home as scheduled. Pritchett discusses several approaches, including the pros and cons of establishing and regulating commercial labor brokers.

Pritchett suggests that rich countries enter into bilateral agreements with developing countries to govern temporary labor. He predicts that agreements between just two countries, or between small groups of countries, will be more politically acceptable than an overall agreement through a large multilateral organization such as the World Trade Organization. "For many reasons--security, historical links, concerns about culture clash--host countries will be more willing to engage in bilateral agreements with selected sending countries," he says.

To enhance the development impact of temporary workers on their countries of origin, Pritchett suggests a wide range of measures, including enabling the sending country to collect taxes and public pension contributions and lowering the cost of sending remittances.