As donors gather next week in Rome to pledge funds to the International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD), they may be wondering where the United States is. During a recent debate on the floor of the US House of Representatives, Congresswoman Maxine Waters raised the possibility that the Trump administration may not make a pledge to IFAD. If true, this would represent the loss of the fund’s largest donor and could jeopardize funding from other donors this year. Given the generally high marks this independent fund earns for development effectiveness, the uncertainty around a US pledge is troubling.

In this “America First” moment, it’s worth asking when it comes to IFAD, what’s in it for the United States and what will be lost if the United States drops out?

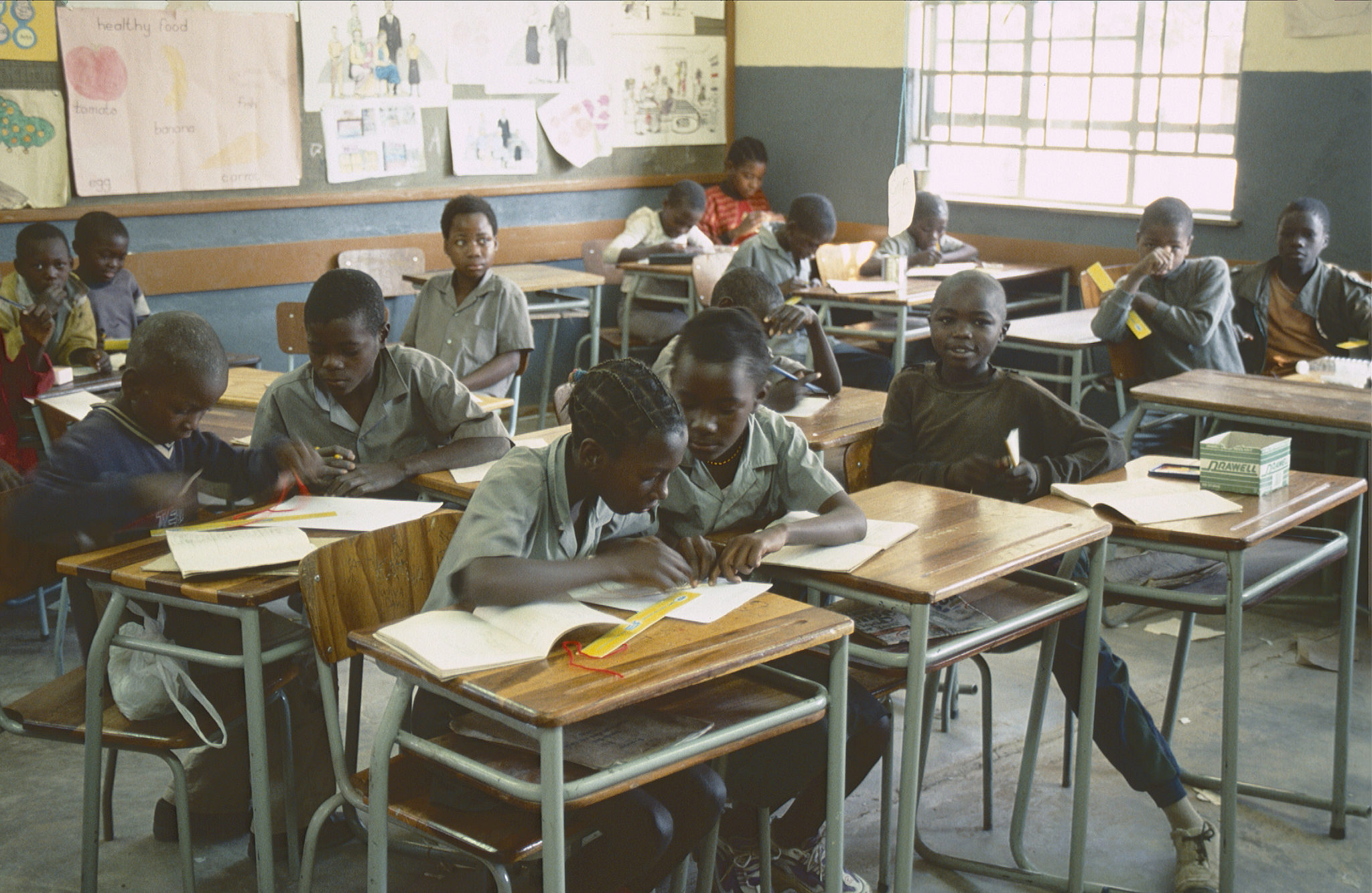

IFAD is the only multilateral institution dedicated exclusively to eradicating poverty and hunger in rural areas of developing countries. It was established in 1977 as one of the major outcomes of the 1974 World Food Conference, which was organized in response to the food crises of the early 1970s. To date it has granted or lent about US$12.9 billion for over 1,000 agriculture and rural development programs in 124 different countries.

The need for this support is clear. According to the 2017 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, for the first time since 2003 the number of chronically undernourished people in the world has increased, up to 815 million from 777 million in 2015. And the Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that keeping pace with population growth in the developing world will require a 50 percent increase in the production of food and other agricultural products between 2012 and mid-century.

Because most of IFAD’s financing is provided at highly concessional rates that low-income countries can afford, its capital must be periodically replenished in order to prevent a drop in lending capacity. Next week, the fund’s 176 members will wrap up discussions on the parameters for the eleventh such replenishment and the fund’s donors will make their pledges.

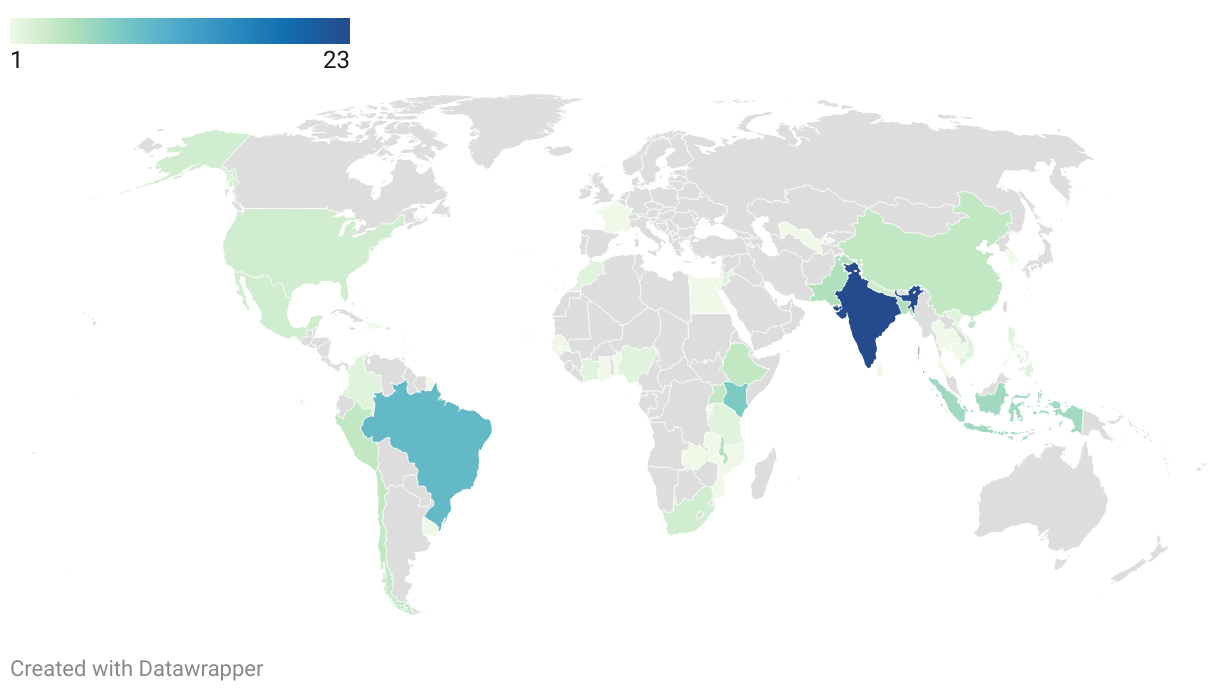

Reflecting its economic status and long-standing leadership role in the multilateral system, the United States has traditionally been the largest single contributor to IFAD replenishments. Its US$90 million pledge to the Tenth Replenishment of IFAD’s resources (2016-2018) represented 8.7 percent of the total. While significant, this share is much smaller than is the case for other international funding bodies, such as the Global Fund (33 percent) or the World Bank’s International Development Association (17 percent). Moreover, this US$90 million pledge helps leverage financing that enables IFAD to support a $7 billion program of work, representing a remarkable “leverage” ratio of almost 80 to 1.

IFAD has had a practice of complementing US bilateral assistance programs, thus magnifying the impact of USAID’s work. For example, in northern Ghana, USAID and IFAD have worked together to improve the production and distribution of maize, soya, and sorghum by smallholder farmers. IFAD, USAID, and the US Department of Agriculture have also worked together on agricultural research and pest eradication, including the highly successful eradication of the screwworm in North Africa.

Whatever reason US officials might decide to withhold a pledge from IFAD, it can’t be due to the fund’s effectiveness. In a joint CGD-Brookings assessment, IFAD outscored US bilateral assistance on all dimensions. And another recent independent assessment noted that IFAD has sound fiduciary policies and practices and is fully committed to a results agenda.

When it comes to a US pledge, the good news may be that congressional support for the fund has been very strong on a bipartisan basis over many years. Even as Congress routinely cut Bush and Obama administration requests for funding to the World Bank and other regional development banks, congressional funding for IFAD was routinely protected. More recently, the US government’s global hunger and food security approach embodied in the bipartisan Global Food Security Act (GFSA) of 2016 closely mirrors the fund’s mandate and strategic priorities. These forces could ultimately prevail upon a reluctant Trump administration to come back to the pledging table sometime this year.

But as all of IFAD’s donors meet next week, it will be important for IFAD’s allies in Congress and elsewhere to make clear that US support for the fund remains strong and any lack of pledge at the moment is a temporary problem.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.