This is one of a series of blogs exploring the issues facing refugees’ economic inclusion within the top refugee and forced migrant hosting countries. All are being authored with local experts, and provide a snapshot of the barriers refugees face and what the policy priorities are going forward. All blogs can be found here.

In the last five years, the exodus of people from Venezuela has become the second largest displacement in the world. More than 5.4 million have fled, with 1.7 million, or 30 percent, ending up in nearby Colombia.

The Government of Colombia has been incredibly generous towards this population, enacting several rounds of work permits which granted the right to work, move, and formalize their status. They should be celebrated for these moves, while supported to overcome the remaining constraints to full economic inclusion.

“Foreigners in Colombia shall enjoy the same civil rights as Colombians”

Article 100 of Colombia’s Constitution states, “Foreigners in Colombia shall enjoy the same civil rights as Colombians.” There are many refugee-hosting countries whose constitutions include similar language, yet few that have followed through on such a promise.

Within just a few years, 1.7 million Venezuelans have entered Colombia, fleeing violence and economic deprivation at home. The Government said they made an immediate decision to facilitate their full economic inclusion for three main reasons:

- Solidarity. Venezuela and Colombia have long shared cultural and economic ties. As a stark example, for the last 50 years, armed fighting in Colombia has created waves of refugees, many of which have ended up in Venezuela. Colombia felt compelled to return the favor.

- Vulnerability. Many Venezuelans arrived in Colombia with few resources. Facilitating their access to work, education, and health, would reduce vulnerability among this population and prevent them turning to crime, child labor, or other measures, to fend for themselves. It is also a way to address the growing humanitarian crisis across the border (e.g., through remittances).

- Practicality. On average, those displaced are younger and more educated than the Colombian population. These waves are also unlikely to stop any time soon, even if president Maduro resigns, and closing the border is impossible. Integrating Venezuelans is therefore the more practical and most beneficial thing to do—an opportunity for Colombia to promote economic, social, and cultural growth.

To implement this approach, the president’s office created a new position: Manager of the Colombian-Venezuelan border, with an associated office. The National Planning Department, with the support of this office, issued the CONPES 3950, a policy document detailing the strategy for integrating Venezuelans over the next three years. The document strongly argues that migration is not just an opportunity for the migrants, but also for receiving countries.

The Challenges in Regularizing 1.7 Million People

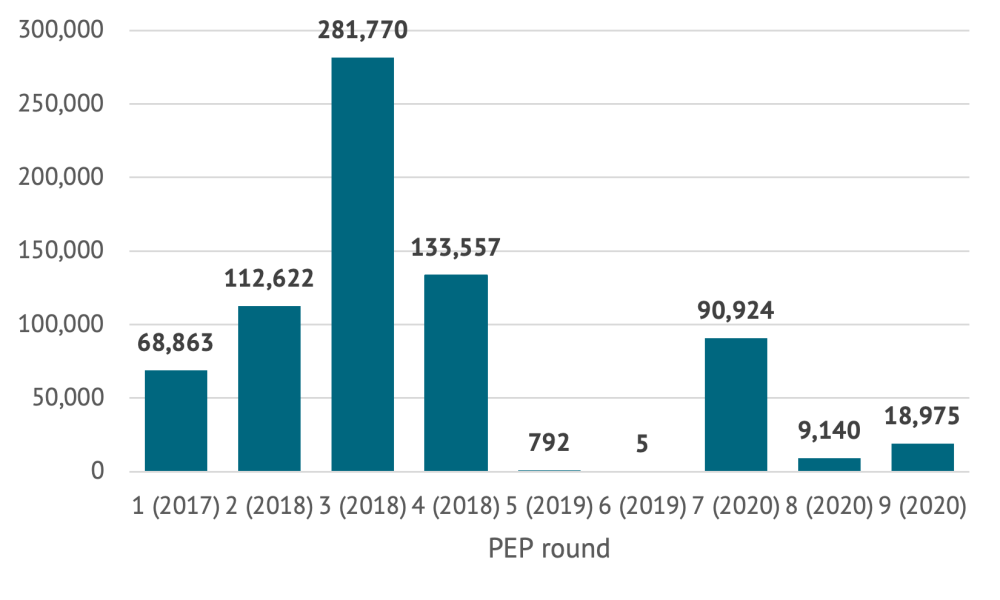

Still, economically integrating such a large population has come with its challenges. In 2017, the Government of Colombia created the Permiso Especial de Permanencia (PEP), a temporary and ad hoc special permit. It granted Venezuelans two years of regular status, work authorization, and access to public services, and could be renewed once. So far, just over 700,000 PEP’s have been granted, and researchers have found little evidence that the provisions have changed labor market outcomes for Venezuelans or Colombians.

Figure 1. The Evolution of the PEPs (2017-2020)

Sources: Migración Colombia (2020)

In addition, many Venezuelans have missed out on the PEP due to its prohibitive requirements. For example, if Venezuelans who entered Colombia missed the window to apply, they are not able to access the work permit. Those who arrived irregularly are also not eligible, even though the institutional and economic collapse within Venezuela means accessing official documents is difficult, leaving irregular movement as the only choice. Only 299 Venezuelans have been able to obtain refugee status in Colombia, out of only 10,479 asylum applications.

With or without the PEP, many Venezuelans face barriers in finding formal jobs that match their skills. Without formal work authorization, 70 percent of Venezuelans have been pushed into the informal sector. Across both formal and informal sectors, on average, Venezuelans earn $92 less than Colombians every month. 89 percent of those with foreign diplomas have faced difficulty getting those credentials accredited.

Women are particularly affected. Despite being more educated than Colombian women, less than 10 percent of Venezuelan women have formal jobs. Even those who can work are in the wrong place. Many are in border areas, such as Villa del Rosario, Maicao, or Cúcuta, where there are fewer opportunities.

Reducing Host Community Support

Such pressures have impacted the way host communities in Colombia view the Venezuelan population. Between 2016 and 2019, Colombia dropped 2.15 points on Gallup’s Migrant Acceptance Index, the third largest drop (after Peru and Ecuador, both recipient countries of Venezuelans).

Venezuelans are blamed for lower wages, worsening working conditions, and rising crime. For example, a 2019 study by Oxfam found that 56 percent of Colombians felt Venezuelans take more than they put in, despite the evidence of contributions to GDP.

As a result, Colombians’ support for their welcoming policy has lessened. In February 2019, 34 percent of Colombians disapproved of their government’s handling of the Venezuelan crisis. By July 2019, this was up to 56 percent, and by October 2020, it was up to 80 percent.

Politicians have exploited this, and surveys show a correlation between political statement and public beliefs. Support for right-wing political parties in areas with large Venezuelan concentrations has increased. Addressing the outstanding barriers to Venezuelan economic inclusion, in a way that is inclusive of host communities and actively engages with these worsening views, will be crucial.

The Impact of COVID-19

Colombia has been hit hard by the pandemic. Over 40,000 people have died of the virus and Colombia’s GDP is predicted to fall by almost 8 percent, leading the country into its first recession in two decades. The work permit restrictions outlined above meant Venezuelans were crowded into sectors highly impacted by the pandemic, like food services and manufacturing. 37 percent of Venezuelans in Colombia lost their jobs.

The situation is even worse for women. 78 percent of employed Venezuelan women in Colombia were working in sectors highly impacted by the pandemic. Now, 31 percent of Venezuelan women are unemployed. As a result, despite the closure of the border in March 2020, more than 100,000 Venezuelans have elected to return home. The pandemic has also exacerbated host community concerns, with many Colombians associating Venezuelans and continuing cross-border movement with the spread of disease.

As the border re-opens, for every one Venezuelan returning home, it is estimated that there would be two entering Colombia. This will put further pressure on border towns and has therefore led Colombia to call for more humanitarian assistance. The 2021 Refugee and Migrant Response Plan (RMRP) has called for more than US$1.44 million to address humanitarian and integration challenges across Latin America. Colombia needs nearly half of it. Yet past experiences suggest receiving this funding is unlikely.

Expanding Economic Inclusion in Colombia

In 2019, the Border Manager’s Office created an Income Generation Strategy which identified the barriers Venezuelans face to full economic inclusion. Together with the Labor Migration Policy Management Group of the Ministry of Labor, they have begun by working on entrepreneurship, employment, financial inclusion, and credentialing. For example, the government has provided more than 5,000 professional recognition certificates through the National Learning Service.

They also created a new permit in January 2020. The Permiso Especial de Permanencia para el Fomento a la Formalización (PEP-FF) allows Venezuelans in an irregular situation with a formal job offer to regularize their status. According to Migración Colombia, by December, more than 9,000 PEP-FF’s had been granted.

Nevertheless, concerns with both of these measures remain. The Income Generation Strategy has not been fully implemented and barriers remain, many of which have been exacerbated by COVID-19. And while the PEP-FF is an innovative measure, it poses several protection risks. Tying regular status to an employment contract exposes workers to potential exploitation and abuse. The permit cannot be extended to family members, and therefore does little to reduce their vulnerability. Finally, the holder can fall back into irregularity when the permit ends.

Combatting these remaining barriers is going to take a coalition of the national and local governments, private sector actors, donors, and local NGOs. For example, planned and voluntary movement would ensure Venezuelans can access existing job opportunities, and targeted matching and training programs would ensure Venezuelans can access new ones. The private sector needs to be more involved than it has been to date, promoting the benefits of hiring Venezuelans and expanding financial service. Finally, women should be explicitly targeted with policies to support childcare and family responsibilities.

It is not often you see a country state clearly, pragmatically, and early the reasons why the economic integration of a new population should be prioritized, and then for that country to take pragmatic steps to execute this vision. Barriers remain, and COVID-19 has exacerbated them, but as long as such leadership remains in place, these challenges appear surmountable.

Este blog forma parte de una serie que explora los problemas que tienen los refugiados para lograr su inclusión económica dentro de los países que más refugiados y migrantes forzosos reciben. Todos estos blogs están siendo escritos con autores locales y analizan las barreras que los refugiados encuentran y cuáles deberían ser las prioridades de aquí en adelante. Todos los blogs se pueden leer aquí.

En los últimos cinco años, el éxodo de personas de Venezuela se ha convertido en el segundo mayor desplazamiento del mundo. Más de 5,4 millones han huido, y 1,7 millones, es decir, el 30%, han acabado en Colombia.

El gobierno de Colombia ha sido increíblemente generoso con esta población, ofreciendo varias rondas de permisos de trabajo que conceden el derecho a trabajar, desplazarse y formalizar su estatus legal. Hay que celebrar estas acciones y, al mismo tiempo, ofrecer apoyo para que superen las limitaciones que aún existen y que impiden la plena inclusión económica de los venezolanos.

"Los extranjeros en Colombia gozarán de los mismos derechos civiles que los colombianos"

El artículo 100 de la constitución de Colombia dice: Los extranjeros disfrutarán en Colombia de los mismos derechos civiles que se conceden a los colombianos." Hay muchos países que acogen refugiados cuyas constituciones incluyen declaraciones similares, pero pocos han cumplido esta promesa.

En pocos años, 1,7 millones de venezolanos han entrado en Colombia, huyendo de la violencia y de los problemas económicos en su país. El gobierno colombiano dijo que tomó la decisión de facilitar su plena inclusión económica

- Solidaridad. Venezuela y Colombia comparten desde hace mucho tiempo vínculos culturales y económicos. Por ejemplo, durante los últimos 50 años, los combates armados en Colombia han generado oleadas de refugiados, muchos de las cuales han acabado en Venezuela. Colombia sintió que debía devolver el favor.

- Vulnerabilidad. Muchos venezolanos llegaron a Colombia con pocos recursos. Facilitar su acceso al trabajo, a la educación y a la salud, reduciría la vulnerabilidad de esta población y evitaría que recurrieran a la delincuencia, al trabajo infantil o a otras medidas, para valerse por sí mismos. Esto también es una forma de abordar la creciente crisis humanitaria al otro lado de la frontera (a través, por ejemplo, de mayores remesas).

- Pragmatismo. Los desplazados (en promedio) son más jóvenes y tienen más educación que la población colombiana, es poco probable que estas oleadas se detengan pronto, incluso si el presidente Maduro dimite, y cerrar la frontera es imposible. Por tanto, integrar a los venezolanos es lo más práctico y beneficioso y una oportunidad para que Colombia promueva su crecimiento económico, social y cultural.

Para implementar las medidas de integración, la oficina del presidente creó un nuevo cargo: Gerente de la frontera colombo-venezolana, con una oficina asociada. El Departamento Nacional de Planificación, con el apoyo de esta oficina, emitió el

Los retos a la hora de regularizar a 1,7 millones de personas

Pese a las buenas intenciones, integrar económicamente a una población tan numerosa supone importantes desafíos. En 2017, el Gobierno de Colombia creó el Permiso Especial de Permanencia (PEP), un permiso temporal y ad hoc. El PEP concedía a los venezolanos dos años de estatus legal, el permiso de trabajo y el acceso a los servicios públicos y podía renovarse una vez. Hasta ahora, se han concedido poco más de 700.000 PEP y se han encontrado pocas pruebas de que esta regulación haya cambiado afectado significativamente la situación de venezolanos o colombianos en el mercado laboral.

Figura 1. La evolución de los PEP (2017-2020)

Fuente: Migración Colombia (2020)

Además, muchos venezolanos no han podido acceder al PEP debido a ciertos requisitos prohibitivos. Por ejemplo, si dejaron pasar el periodo de tiempo máximo para solicitarlo, no pueden acceder al permiso de trabajo. Los que llegaron de forma irregular tampoco pueden solicitar el PEP, lo cual es problemático dado que el colapso institucional y económico de Venezuela dificulta el acceso a los documentos oficiales y deja como única opción la circulación irregular. Sólo 299 venezolanos han podido obtener el estatus de refugiado en Colombia, de sólo 10.479 solicitudes de asilo.

Con o sin el PEP, muchos venezolanos se enfrentan dificultades para encontrar trabajos formales que se ajusten a sus habilidades. Sin una autorización para trabajo formalmente, el 70% de los venezolanos se han visto empujados al sector informal.

Tanto en el sector formal como en el informal, los venezolanos ganan en promedio 92 dólares mensuales menos que los colombianos y el 89% de los venezolanos que tienen diplomas extranjeros han tenido dificultades para convalidar esas credenciales. A pesar de estar más educadas que las colombianas, las mujeres venezolanas se ven particularmente afectadas, menos del 10 por ciento tienen empleos formales. Incluso las que pueden trabajar están en el lugar equivocado ya que se encuentran desproporcionadamente en zonas fronterizas, como Villa del Rosario, Maicao o Cúcuta, donde hay menos oportunidades.

Menos apoyo de la comunidad de acogida

Las presiones migratorias han impactado la forma en que las comunidades de acogida en Colombia ven a la población venezolana. Entre 2016 y 2019, Colombia cayó 2,15 puntos en el Índice de Aceptación de Migrantes de Gallup, la tercera mayor caída (después de Perú y Ecuador, ambos países también receptores de venezolanos).

A los venezolanos se les culpa por la bajada de los salarios, por el empeoramiento de las condiciones laborales y por aumento de la delincuencia. Por ejemplo, un estudio realizado en 2019 por Oxfam encontró que el 56 por ciento de los colombianos sentía que los venezolanos se “llevan más de lo que aportan”, a pesar de la evidencia de sus contribuciones al PIB.

Como resultado, el apoyo de los colombianos a su política de acogida ha disminuido. En febrero de 2019, el 34 por ciento de los colombianos desaprobaba el manejo de la crisis por parte de su gobierno. En julio de 2019, este número había subido al 56 por ciento, y en octubre de 2020, al 80 por ciento.

Los políticos han explotado esto y las encuestas demuestran una correlación entre las declaraciones de políticos y la percepción públicas. El apoyo a los partidos políticos de derecha en las zonas con grandes concentraciones de venezolanos ha aumentado. Es crucial abordar las barreras que enfrenta la inclusión económica de los venezolanos de una manera que incluya a las comunidades de acogida y se trate activamente del deterioro de las opiniones sobre la población inmigrante.

El artículo 100 de la constitución de Colombia dice: Los extranjeros disfrutarán en Colombia de los mismos derechos civiles que se conceden a los colombianos." Hay muchos países que acogen refugiados cuyas constituciones incluyen declaraciones similares, pero pocos han cumplido esta promesa.

En pocos años, 1,7 millones de venezolanos han entrado en Colombia, huyendo de la violencia y de los problemas económicos en su país. El gobierno colombiano dijo que tomó la decisión de facilitar su plena inclusión económica

- Solidaridad. Venezuela y Colombia comparten desde hace mucho tiempo vínculos culturales y económicos. Por ejemplo, durante los últimos 50 años, los combates armados en Colombia han generado oleadas de refugiados, muchos de las cuales han acabado en Venezuela. Colombia sintió que debía devolver el favor.

- Vulnerabilidad. Muchos venezolanos llegaron a Colombia con pocos recursos. Facilitar su acceso al trabajo, a la educación y a la salud, reduciría la vulnerabilidad de esta población y evitaría que recurrieran a la delincuencia, al trabajo infantil o a otras medidas, para valerse por sí mismos. Esto también es una forma de abordar la creciente crisis humanitaria al otro lado de la frontera (a través, por ejemplo, de mayores remesas).

- Pragmatismo. Los desplazados (en promedio) son más jóvenes y tienen más educación que la población colombiana, es poco probable que estas oleadas se detengan pronto, incluso si el presidente Maduro dimite, y cerrar la frontera es imposible. Por tanto, integrar a los venezolanos es lo más práctico y beneficioso y una oportunidad para que Colombia promueva su crecimiento económico, social y cultural.

Para implementar las medidas de integración, la oficina del presidente creó un nuevo cargo: Gerente de la frontera colombo-venezolana, con una oficina asociada. El Departamento Nacional de Planificación, con el apoyo de esta oficina, emitió el

Los retos a la hora de regularizar a 1,7 millones de personas

Pese a las buenas intenciones, integrar económicamente a una población tan numerosa supone importantes desafíos. En 2017, el Gobierno de Colombia creó el Permiso Especial de Permanencia (PEP), un permiso temporal y ad hoc. El PEP concedía a los venezolanos dos años de estatus legal, el permiso de trabajo y el acceso a los servicios públicos y podía renovarse una vez. Hasta ahora, se han concedido poco más de 700.000 PEP y se han encontrado pocas pruebas de que esta regulación haya cambiado afectado significativamente la situación de venezolanos o colombianos en el mercado laboral.

Figura 1. La evolución de los PEP (2017-2020)

Fuente: Migración Colombia (2020)

Además, muchos venezolanos no han podido acceder al PEP debido a ciertos requisitos prohibitivos. Por ejemplo, si dejaron pasar el periodo de tiempo máximo para solicitarlo, no pueden acceder al permiso de trabajo. Los que llegaron de forma irregular tampoco pueden solicitar el PEP, lo cual es problemático dado que el colapso institucional y económico de Venezuela dificulta el acceso a los documentos oficiales y deja como única opción la circulación irregular. Sólo 299 venezolanos han podido obtener el estatus de refugiado en Colombia, de sólo 10.479 solicitudes de asilo.

Con o sin el PEP, muchos venezolanos se enfrentan dificultades para encontrar trabajos formales que se ajusten a sus habilidades. Sin una autorización para trabajo formalmente, el 70% de los venezolanos se han visto empujados al sector informal.

Tanto en el sector formal como en el informal, los venezolanos ganan en promedio 92 dólares mensuales menos que los colombianos y el 89% de los venezolanos que tienen diplomas extranjeros han tenido dificultades para convalidar esas credenciales. A pesar de estar más educadas que las colombianas, las mujeres venezolanas se ven particularmente afectadas, menos del 10 por ciento tienen empleos formales. Incluso las que pueden trabajar están en el lugar equivocado ya que se encuentran desproporcionadamente en zonas fronterizas, como Villa del Rosario, Maicao o Cúcuta, donde hay menos oportunidades.

Menos apoyo de la comunidad de acogida

Las presiones migratorias han impactado la forma en que las comunidades de acogida en Colombia ven a la población venezolana. Entre 2016 y 2019, Colombia cayó 2,15 puntos en el Índice de Aceptación de Migrantes de Gallup, la tercera mayor caída (después de Perú y Ecuador, ambos países también receptores de venezolanos).

A los venezolanos se les culpa por la bajada de los salarios, por el empeoramiento de las condiciones laborales y por aumento de la delincuencia. Por ejemplo, un estudio realizado en 2019 por Oxfam encontró que el 56 por ciento de los colombianos sentía que los venezolanos se “llevan más de lo que aportan”, a pesar de la evidencia de sus contribuciones al PIB.

Como resultado, el apoyo de los colombianos a su política de acogida ha disminuido. En febrero de 2019, el 34 por ciento de los colombianos desaprobaba el manejo de la crisis por parte de su gobierno. En julio de 2019, este número había subido al 56 por ciento, y en octubre de 2020, al 80 por ciento.

Los políticos han explotado esto y las encuestas demuestran una correlación entre las declaraciones de políticos y la percepción públicas. El apoyo a los partidos políticos de derecha en las zonas con grandes concentraciones de venezolanos ha aumentado. Es crucial abordar las barreras que enfrenta la inclusión económica de los venezolanos de una manera que incluya a las comunidades de acogida y se trate activamente del deterioro de las opiniones sobre la población inmigrante.

impacto del COVID-19

Colombia se ha visto muy afectada por la pandemia. Más de 40.000 personas han muerto a causa del virus y se prevé que el PIB de Colombia caiga casi un 8 por ciento, lo que llevará al país a su primera recesión en dos décadas. Las limitaciones de los permisos de trabajo mencionados anteriormente hicieron que los venezolanos se aglutinaran en sectores muy afectados por la pandemia, como los servicios de alimentación y la industria manufacturera. Como resultado, el 37% de los venezolanos en Colombia perdió su empleo.

La situación es aún peor para las mujeres: el 78 por ciento de las mujeres venezolanas empleadas en Colombia trabajaban en sectores que fueron fuertemente golpeados por la pandemia y ahora, el 31 por ciento de las mujeres venezolanas están desempleadas. Como resultado, a pesar del cierre de la frontera en marzo de 2020, más de 100.000 venezolanos han optado por regresar a su país.

La pandemia también ha exacerbado las preocupaciones de la comunidad de acogida, ya que muchos colombianos asocian a los venezolanos y el continuo movimiento transfronterizo con la propagación de la enfermedad. Con la reapertura de la frontera, se estima que por cada venezolano que regrese a su país, habrá dos que entren en Colombia. Esto supondrá una mayor presión sobre las ciudades fronterizas y ha llevado a Colombia a solicitar más ayuda humanitaria. El Plan de Respuesta a Refugiados y Migrantes (RMRP por sus siglas en inglés) ha solicitado más de 1,44 millones de dólares para hacer frente a las dificultades humanitarias y de integración en América Latina. Colombia necesita casi la mitad de estos fondos. Sin embargo, si nos basamos en experiencias pasadas, es poco probable que reciba esta financiación.

>Expandiendo la inclusión económica en Colombia

En 2019, la Gerencia de Fronteras creó una Estrategia de Generación de Ingresos que identificó las barreras que enfrentan los venezolanos para lograr una plena inclusión económica. Junto con el Grupo de Gestión de la Política Migratoria Laboral del Ministerio del Trabajo, han comenzado por fomentar el emprendimiento, el empleo, la inclusión financiera y la credencialización. Dentro de esta estrategia, el gobierno ha entregado más de 5.000 certificados de reconocimiento profesional a través del Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje.

También crearon un nuevo permiso en enero de 2020, el Permiso Especial de Permanencia para el Fomento a la Formalización (PEP-FF), que permite a los venezolanos en situación irregular con una oferta de trabajo formal regularizar su situación. Según el departamento de Migración de Colombia, hasta diciembre se habían concedido más de 9.000 PEP-FF.

Sin embargo, sigue habiendo preocupación en torno a ambas medidas. La Estrategia de Generación de Ingresos no se ha implementado en su totalidad y siguen existiendo barreras, muchas de las cuales han sido exacerbadas por el COVID-19. Y, aunque el PEP-FF es una medida innovadora, plantea varios riesgos en materia de protección. Vincular el estatus de regularidad a un contrato de trabajo expone a los trabajadores a posibles explotaciones y abusos. El permiso no puede hacerse extensivo a los miembros de la familia, por lo que apenas contribuye a reducir su vulnerabilidad y, por último, el titular puede volver a caer en la irregularidad cuando finaliza el permiso.

Para combatir los obstáculos que aún persisten será necesaria la colaboración de gobiernos nacionales y locales, agentes del sector privado, donantes y ONG locales. Por ejemplo, facilitar una migración planificada y voluntaria garantizaría el acceso de los venezolanos a las oportunidades de trabajo existentes y los programas de capacitación y adecuación específicos podrían garantizar el acceso de los venezolanos a nuevos puestos de trabajo. El sector privado debe implicarse más de lo que lo ha hecho hasta ahora, enfatizando las ventajas de contratar a venezolanos y ampliando los servicios financieros. Por último, las mujeres estar específicamente consideradas en las políticas de apoyo, con medidas que apoyen el cuidado de sus hijos y ayuden en las tareas del hogar.

No es frecuente ver a un país exponer de forma tan rápida, clara y pragmática las razones por las que debe priorizarse la integración económica de una nueva población. Menos aún que este país tome medidas prácticas para ejecutar esta visión. Siguen existiendo obstáculos y desafíos considerables que el COVID-19 ha exacerbado, pero mientras se mantengan esta voluntad y liderazgo, estos retos parecen ser superables.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: IMF Photo/Joaquin Sarmiento