The Women, Business and the Law program at the World Bank has done a wonderful job of cataloguing the thousands of legal restrictions worldwide that constrain women’s abilities to be equal participants in the economy—from legislation mandating women ask a male family member for permission before opening a bank account through rules banning women from certain jobs to unequal property rights. Pairing that data with surveyed outcomes would make it an even more powerful tool.

The Women, Business and the Law team provides numerous illustrations, from statistical associations to case studies, of the link between laws and women’s empowerment. For example, in 2009, a woman applied to be an assistant driver in the St. Petersburg subway system and was turned down because the law prohibits women from holding the job. She challenged this in court on grounds of gender discrimination, but the Supreme Court of the Russian Federation rejected her argument.

"Men conductors required," artist unknown, 1951, and "London Transport needs women conductors," artist unknown, 1957. Perhaps one day in St Petersburg? Source: London Transport Museum

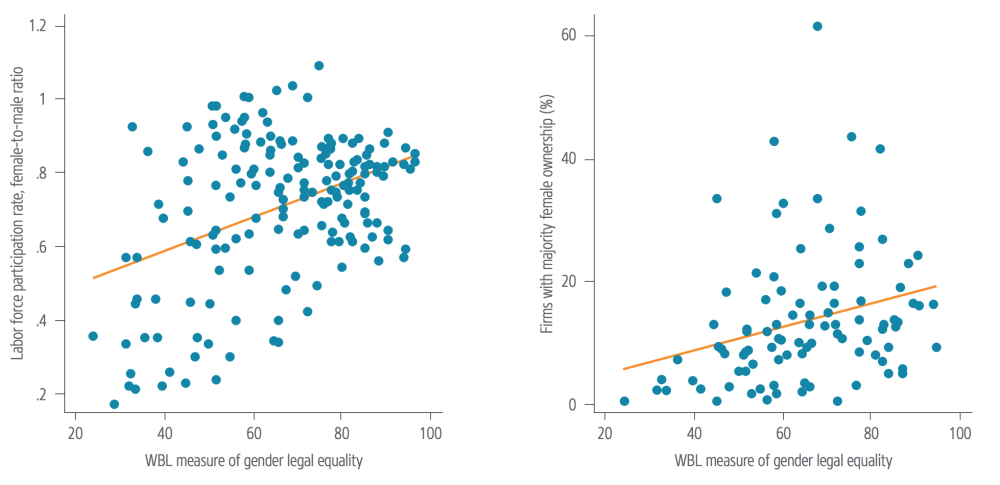

Overall and across countries, lower legal gender equality is associated with fewer girls attending secondary school relative to boys, fewer women working or running businesses, and a wider gender wage gap.

With less gender legal equality in an economy, fewer women work or own a business

Source: Women, Business and the Law 2018

Women, Business and the Law research also suggests how much details can matter to the impact of laws: both Bolivia and the Democratic Republic of Congo require that 50 percent of political party candidates are women, but 53 percent of members of Bolivia’s parliament are women compared to 9 percent in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The researchers suggest the DRC law may be ineffectual because it is silent on both placement requirements and sanctions for noncompliance.

Women, Business and the Law was incubated by the World Bank’s Doing Business group, which catalogues the legal and regulatory steps necessary to launch and run a business—the official number of steps and length of time taken to get permission to build a warehouse or set up a limited liability company, for example. As with legal barriers to women’s economic empowerment, the effect of de jure regulations on actual outcomes can be varied.

That is easy to see with Doing Business because the World Bank also runs a series of enterprise surveys which ask some of the same questions as Doing Business, but seeking data on actual de facto experiences rather than recording what should be the case following the laws and regulations on the books. The relationship between de jure and de facto can be extremely weak. Mary Hallward-Driemeier and Lant Pritchett demonstrated the gap: they found that the time reported for getting a construction permit in Doing Business was 177 days. The Enterprise Survey data suggested a median of 30 days, and there was a very weak relationship between longer de jure and longer de facto processes.

Again, the Women, Business and the Law researchers as well as others have demonstrated that the laws they catalogue are related to outcomes. But just as with Doing Business, which legal restrictions are the most binding surely varies—across types of restriction and jurisdictions. The more that Women, Business and the Law data on de jure statutes can be paired with data on their de facto operation, the more useful it will be for policymakers and others trying to prioritize and focus reform efforts. And, over time and as reforms happen, this combination of data will help demonstrate the impact of legal changes.

Beyond compiling already-extant data to link outcomes to laws (Demographic and Household Survey measures of the female genital mutilation rates to laws banning the practice, for example), two additional survey approaches might help. For some of the restrictions, a few additional questions on the enterprise survey might be appropriate: for example, does the firm provide (paid) maternity leave, does it guarantee an equivalent position after leave? (At the same time, enterprise surveys could also improve their precision around women-owned enterprises). In other cases, perhaps a (stand-alone) survey of individual women might be necessary—did you need male family member’s permission to open a bank account? Who is in charge of marital property? Better linking de jure regulation to de facto implementation and on to empowerment outcomes would be a powerful lever for those campaigning for effective legal reform.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.