Recommended

Blog Post

Last week more than 100 countries sent delegations to the Transforming Education Summit. A big moment for global education, this was meant to be an opportunity to “elevate education to the top of the global political agenda”. As we predicted there was little sign of anything transforming, or of any kind of binding international agreement on educational standards or new investment of cash (with one notable exception).

Still, at the UN, talks matter. This meeting was preceded by a lot of talks—including a consultation in each country which was supposed to produce a national “statement of commitment” for presentation at the summit. The UN guidance for the national consultations suggested that they include “whole-of-government” (health, labour, environment ministries etc.) as well as students, youth, teacher unions, academia, religious organisations—the list continues.

It was then the job of the appointed national convenor—often UNICEF—to synthesise the views of all these constituencies into one succinct document. This process is a recipe for including everything and prioritising nothing. Nonetheless, analysis of the statement of commitment from the 106 countries that submitted one proves quite interesting.

We analysed the text of 106 statements to reveal the education priorities emanating from national consultations

Each statement of national commitment was analysed for keywords, categorised into broad education topics (table 1). We present the results of this analysis below. This methodology of course has its caveats: it’s easy to include education buzz words without any policy intent or commitment. And our list of keywords almost certainly omits some important education topics.

Table 1. Keyword Categorization

|

Category |

Key words |

|

Girls education |

Girls, gender, girl, female |

|

School safety |

Violence, safety, abuse |

|

Foundational |

“Foundational literacy and numeracy” “foundational learning” “learning crisis” |

|

Employment |

Skills, vocational, technical, employment |

|

Technology |

Digital, technology, ict |

|

Data |

Data, evidence, research |

|

Funding |

Finance, spend |

|

Secondary |

Secondary |

|

School meals |

Meal, hunger, food, lunch, feed |

|

Learning |

Learning, teaching |

|

Teacher |

Teacher |

|

Climate |

Climate, environment |

|

Inclusive |

Inclusive, disabilities, marginalised, disadvantaged, excluded, equity |

|

Covid-19 |

Covid, coronavirus, pandemic, “learning loss”, remedial |

|

Access |

Access, enrolment |

The results show a strong prioritisation of teaching and learning, but foundational literacy and numeracy and the learning crisis ranked low

Unsurprisingly, teaching, learning, and teachers were the most popular terms in the education statements, with those terms appearing in nearly every statement.

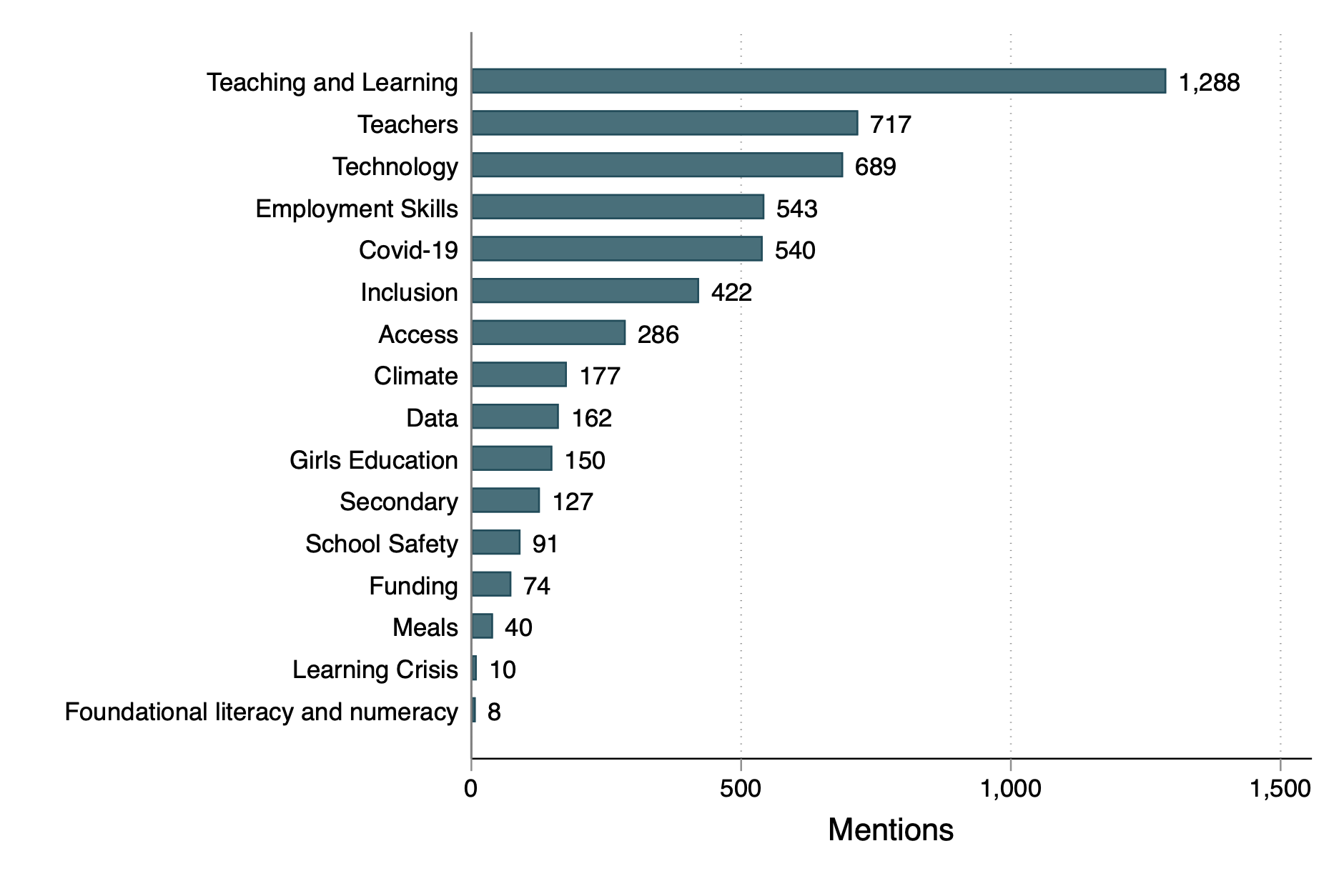

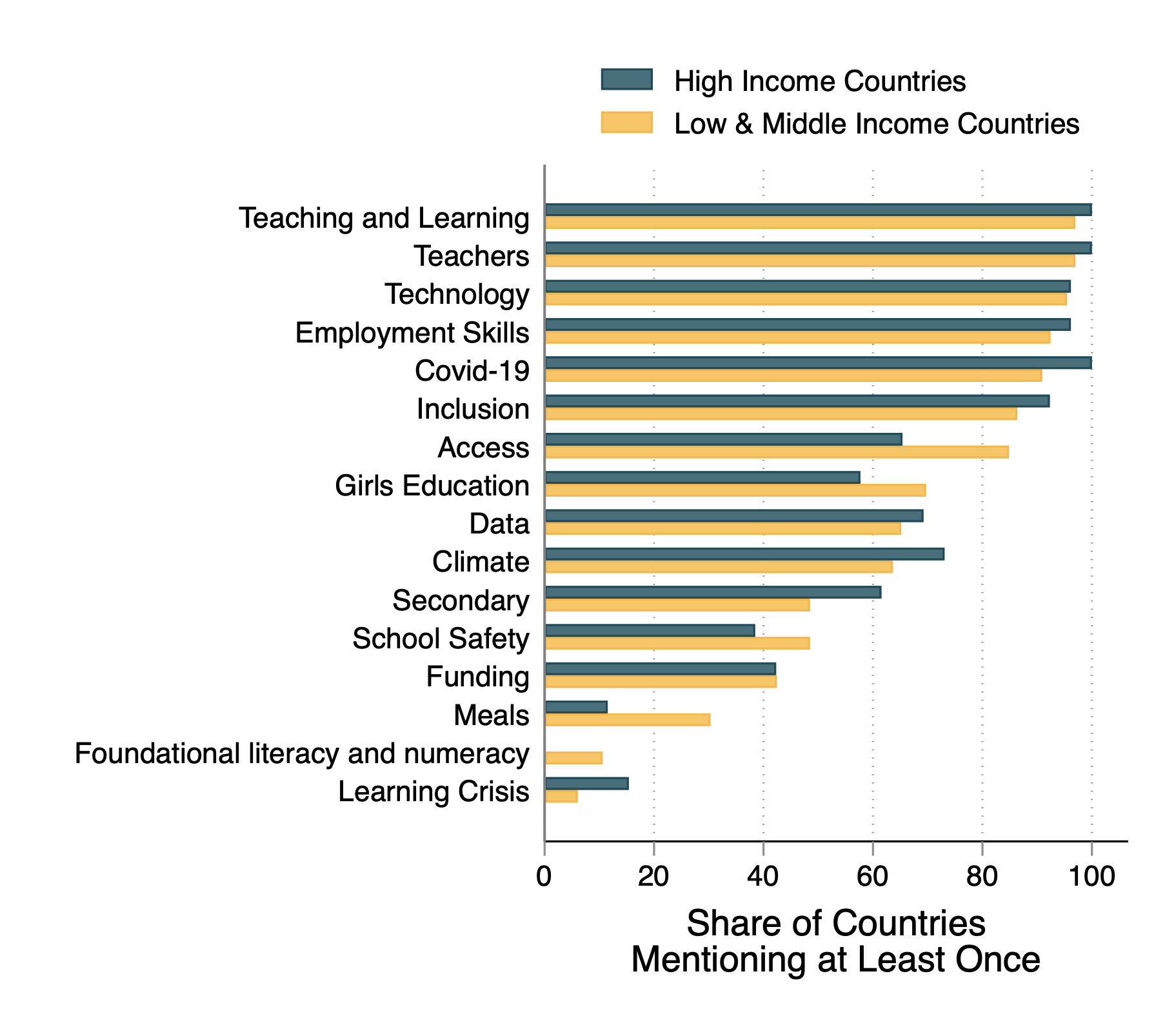

Ahead of the summit, major donors mobilised agencies and countries to sign a “commitment to action on foundational learning”—by which they mostly mean the acquisition of basic reading skills by the age of ten. But despite their best efforts, foundational learning and the learning crisis were remarkably absent from national statements. In fact, they ranked lowest of all the terms we included in our search, both in numbers of mentions (figure 1) and share of countries including those terms (figure 2).

Figure 1. Mentions of core education topics in Statements of Commitment

National education stakeholders care about technology, and employment

Technology (or ICT or digital) came third on our most mentioned topics, just behind teachers. Whilst technology no doubt holds great promise for supporting education in the future, we don’t think anyone would pretend that technology and teachers are comparable assets in an education system.

Employment and skills also showed up as high priorities of policymakers in a CGD poll published last year. In fact, we were able to calculate that officials would choose Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) project over a $10 million budget increase in a different program. This preference is reflected in the national statements—around 90 percent of countries mention these terms. That makes sense: unemployment among youth is a challenge faced by governments in most countries. Empirical studies show that unemployed youth can lead to political instability and even violence, giving governments good reason to focus on investments that promise to address this issue.

Climate change and girls education ranked high

Girls education, another donor favourite, ranked high. Nearly 70 percent of low and middle income countries recognised the need to focus on gender issues in education in their statement (figure 2). Similarly, those pushing for more climate education in schools will be heartened to see that a large majority of low, middle and high income countries included climate change and environmental considerations in their statement.

Figure 2. Share of countries including core education topics in Statements of Commitment

Issues related to child wellbeing had low prominence

Before the summit, CGD researchers had urged leaders at the summit to make concrete commitments on improving child wellbeing in schools. We (and others) called for universal, free school meals. And we asked leaders to make far greater efforts to protect children from abuse in schools. Far too often schools and school systems fail at the core task of keeping children free from hunger and safe from harm and yet these are issues that the education sector can address. However, neither school feeding nor school violence were prominent issues in the statements of national commitment, appearing in less than half of the statements from low and middle income countries.

Explore which core education topics were included in each country’s statement

Using the dropdown box on our interactive map (figure 3) you can choose an education topic and see how many countries included it in their statement.

Figure 3.

Talk may be cheap, but so far most countries aren't even talking about foundational learning and meeting the basic needs of children in school.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.