Measuring empowerment is a perennial challenge for those of us evaluating programs targeting women. Last Wednesday’s launch of J-PAL’s new Practical Guide to Measuring Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment in Impact Evaluations at CGD was an exciting opportunity be inspired by impact evaluation powerhouse Rachel Glennerster, the former Executive Director of J-PAL and current Chief Economist at DFID, while simultaneously getting a bit discouraged about the quality of existing quantitative measures of empowerment. Here are a few takeaways for economists doing impact evaluations.

First, the bad news: the limitations of standardized questions

About those standard DHS questions you were planning to stick in the impact evaluation survey that you’re launching next week—they may not be capturing what you think they are capturing.

As discussed in an earlier J-PAL blog post, Glennerster and her coauthors found that responses to a standard DHS question asking, “Who usually makes decisions about healthcare for yourself?” were only weakly correlated with answers to more concrete questions about whether a woman could purchase medicine for herself or take a sick child to the doctor without her husband’s approval. Moreover, these transparent questions may be subject to social desirability bias (driven by the tendency to give responses that are perceived as socially desirable, whether or not they are accurate) if respondents know that a project is intended to, say, empower women and increase their decision-making power.

The good news—J-PAL has some ideas

So, if we can’t just include the standard DHS questions on decision-making in our survey, what are we to do? The good news is that the J-PAL guide offers a lot of concrete suggestions. First, they recommend replacing those overly general DHS questions with locally appropriate, concrete empowerment measures that you develop yourself—ideally by doing qualitative work to understand “local gender dynamics and the barriers to empowerment” within the specific context of your impact evaluation.

“Wait, what? The J-PAL guide suggests replacing standardized questionnaires with situation-specific qualitative work?”, you say in surprise. Indeed, the unexpected emphasis on qualitative work caused King's College London ethnographer and Twitter superstar Alice Evans to get a little giddy:

Do you run quant impact evaluations?

— Alice Evans (@_alice_evans) July 21, 2018

If so, you'll 😍this guide

Ostensibly on 'empowerment', but very useful for a wider audience.

- Understand context through qual

- Experiment, adapt

- Go beyond the narrow focus on d-m, to consider public goods

👏👏👏https://t.co/X8sZ5eH7Uv pic.twitter.com/IULrucTdfM

Quantifying empowerment is hard work

While the J-PAL guide does provide great resources for economists seeking to better engage with the local context through qualitative work, Glennerster emphasized that this qualitative work was a means to an end: measuring empowerment is difficult, and formative research early in a project can help investigators develop better-powered, situationally-appropriate measures—either survey questions or non-survey measures like lab-in-the-field experiments (more on these below). Early in her talk, Glennerster described her reaction when skeptics suggested that empowerment could not be measured (well) through quantitative work: “People had said ‘Well, empowerment is a process, and it’s about change, and so it’s impossible to quantify’—and my reaction is ‘No! It’s just hard.’” In the Q&A, she went on to say that formative research early in a study was valuable (and worth the extra time and money) because it allowed for the development of concise but accurate survey instruments: “it’s time intensive and labor intensive to get a short questionnaire.”

Moreover, a key point in both the J-PAL guide and Glennerster’s talk was that much of this formative adaptation work is part of what good development economists do as a matter of course anyway:

It’s really important to say that quantitative researchers do this a lot. And then they feel quite embarrassed about talking about it, or there’s certainly no space to talk about it in their paper. So if you read a paper in Econometrica or AER, they’re not going to talk about that first step, where they spent many months… talking to people in the field and understanding their problems and the institutional issues around it... Just because in economics papers there’s no place to put that. And a number of people have said to us: ‘When you don’t talk about that, people think that they can go in and do what you’re doing without doing that step.’ So part of this is just to say—to write down somewhere: actually this is really important to doing a good impact evaluation, that first step of really understanding context.

Pros and cons of context-specific measures

While many development economists would wholeheartedly agree with Glennerster’s view, the need to develop empowerment measures that are specific and appropriate for each new context does raise a few issues.

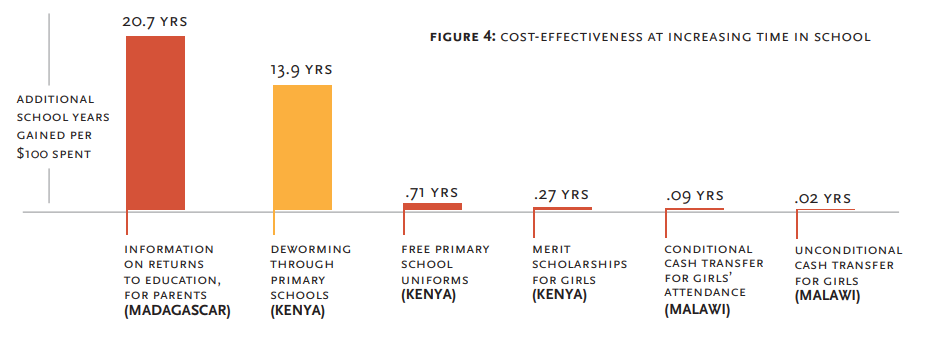

First, of course, there is always a desire to generalize the lessons of successful impact evaluations (and associated concerns about whether such generalizations are justified). If we use a different outcome measure for each study, how will we be able to make figures like this?

So, in defense of those DHS questions, it can be useful to have outcome measures that have already been used in a range of studies—saving us from the world where treatment effects can only be compared in terms of standard deviations.

Second, new measures need to be pre-tested and then validated. One area where I’d like to see more from the J-PAL guide is on the process of validation. For instance, how are we to know if our situationally appropriate question about whether a young girl can go to the movies on her own captures empowerment or just apathetic parenting? How do we assess whether a specific measure is likely to be driven by social desirability bias? How will we know when we’ve arrived at an adapted measure that is ready for prime time?

As if to emphasize the point that qualitative work alone may or may not yield improved survey questions, the guide ends the six-page section on qualitative research with this cautionary tale:

For your ongoing impact evaluation…

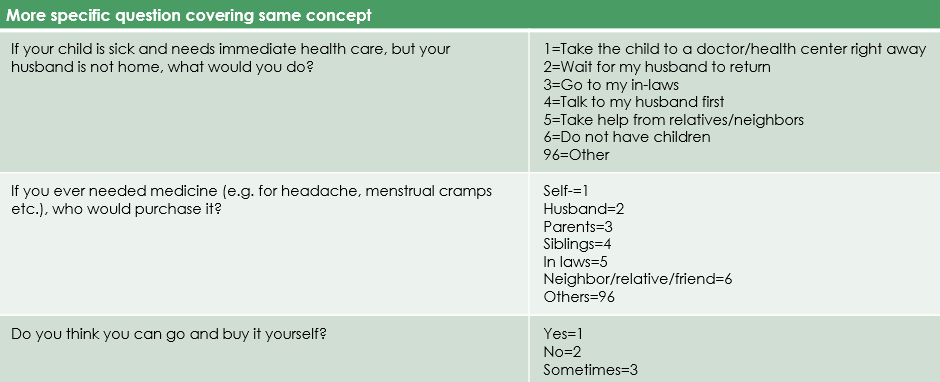

Finally, additional adaptation takes time and money. The J-PAL guidance sounds great—for your next impact evaluation, sure, but what about the one already in the field? Though Glennerster insisted that she was not going to offer any ready-made questions, she actually proposed some pretty nice ones—highlighting specific but broadly applicable questions about decision making that she and her coauthors have been using:

She also highlighted some elegant non-survey instruments. For example, Casey, Glennerster, and Miguel (2012) used structured community activities—objective observations of who speaks and how decisions are made in community meetings—to measure empowerment in Sierra Leone. Almas, Armand, Attanasio, and Carneiro (2018) measure women’s control over resources by eliciting willingness to pay to have a transfer sent to them instead of their husband. As Glennerster put it in her talk, non-survey instruments “are less prone to reporting [i.e., social desirability] bias, and they reveal attitudes that people themselves may not be aware of.” Fellow behavioral development economists take note—we have clearly arrived.

If you want to learn more about J-PAL and Glennerster’s take on measuring women’s empowerment, you can take a look at the new J-PAL guide or watch the video from the launch event.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.