In a new paper, Zack Gehan and I present scenarios for the global economy in 2050. These scenarios build on a forecast of economic growth built around income, population, education, and temperature. The process suggests a considerable degree of uncertainty about how the world will look in three decades, but some things appear relatively predictable. Among those more certain outcomes is that demographic factors and slowing expansion of education in richer countries are likely to spell a period of slower GNI growth, which implies a shrinking share of global output.

The US share of the global economy has dropped from 28 percent in 1950 to about 17 percent today. Our central forecast is for a share of perhaps 12 percent in 2050, while our scenarios suggest a range between 6.7 percent and 18.6 percent. That suggests the best outcome the US could hope for is maintaining its share of the global economy, with the likely forecast being a reduced dominance, in the worst case to about a third of its current share. Similarly, even in the most optimistic of scenarios in terms of relative dominance, the EU at best stands still with a worst case being a 5.8 percent share of the global economy.

Note this is largely a good news story: it is as much about continued growth in the World’s poorest countries (where more income will have the largest impact on global quality of life) as it is about slower growth in the World’s richest ones. And GNI rankings (as opposed to GNI per capita rankings) tell you pretty much nothing about the relative quality of life across countries. But the distribution of output does have implications for global economic institutions where voting power is based in part on the size of member state economies.

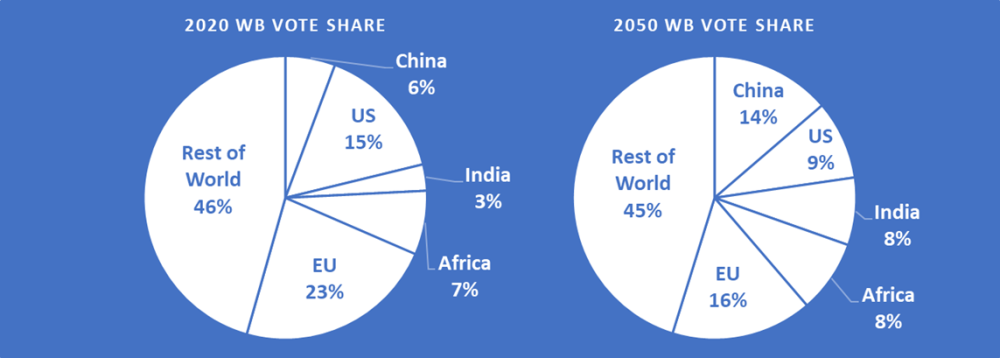

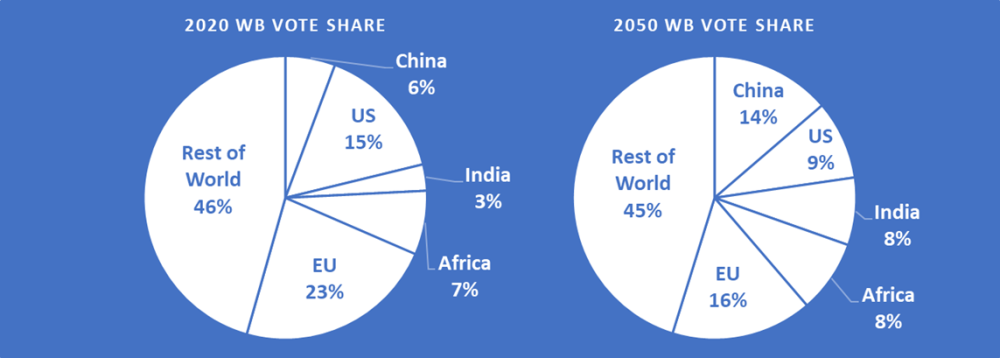

Regarding the World Bank, our central forecast is for about a 9 percent vote share for the US in 2050 (down from 15.5 percent today) with China holding a 14 percent vote share (up from 5.7 percent). If the IMF actually followed its formula for fair allocation of voting power, the US share would probably be somewhere around 10 percent by 2050, well below the 15 percent currently required for veto power under the rules. It is likely (though far from certain) that China would move above the 15 percent threshold.

Central Forecasts for World Bank Vote Shares, 2020 and 2050

In fact, the IMF doesn’t follow its formula for fair allocation of voting power, with many rich countries considerably over-represented. And that raises an increasingly urgent question for policymakers, particularly in Washington. In a world where the US economy is relatively less significant, does the US want smaller, weaker international institutions where it retains more strength to direct and less risk from displeasure, or a world of robust international institutions over which it has less control? So far, the choice appears to be smaller and weaker, with the US snubbing World Trade Organization decisions, and balking at a larger International Monetary Fund and World Bank more reflective of global economic weight.

But that choice is a mistake: The US might want to look at a former global superpower for a lesson as to why. For a while, the UK was doing quite well at “punching above its [remaining] weight” by leaning in to support international institutions. But then it decided to leave its most economically significant international partnership and the result has been weaker economy and scraps-from-the-table trade deals. The less dominant the US is in the global economy, the more it should favor strong international institutions that support mutually beneficial exchange and reduced volatility. In particular, now might be a time to raise the percentage of votes required to veto major decisions at both bodies. While it might reduce US influence in the short term, in the longer term it would likely stop any other single country gaining that veto power.

Having mentioned America’s friends across the Atlantic, Europe’s relative economic weight is likely to fall even further and faster. And yet it still tries to keep a lock on the IMF executive director position as well as an over-share of votes. For the sake of the future, the G-7 club of rich nations should embrace making the IMF and IBRD larger, with shareholdings more reflective of the global economy, and raising the fifteen percent veto threshold.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.