We are grateful for contributions from IQVIA for this piece.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered unprecedented measures by national governments around the world, trade disruptions, and a deep and global economic crisis. All of these factors are, in turn, threatening the supply of essential medicines and other commodities. This is felt most acutely in developing countries (for example, early discussions highlight how Kenya is exposed to medicine shortages), but also in wealthy nations. The widespread nature of these problems reflects a highly complex and highly globalised supply chain for medicines and healthcare commodities. In this blog we outline some of the challenges in the global supply of medicines and introduce a methodology that will enable countries to spot early challenges in supply, allowing them as well as global development partners and industry to plan ahead and pre-empt falling short.

The COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a number of challenges that have led to shortages and price hikes, and could potentially fuel an epidemic of fake and substandard medicines, including:

- severe supply chain blocks caused by significant decreases in air cargo capacity, sea freight, and transport logistics;

- export restrictions by supplier countries related to both COVID-specific commodities, but also non COVID ones (for example India has banned a number of essential active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and finished products, though some of these bans have since been reversed, the UK has banned parallel exports, and EU has restricted exports of protective equipment.)

- the slowdown in production of medicines in affected countries. This began in China with API production (which has now all but resumed there) but also in India, and other key manufacturing bases.

Drawing on the work of the international Decision Support Initiative (iDSI) and CGD’s earlier procurement work, in partnership with colleagues from IQVIA, MaishaMeds, and other in-country partners, a we have set out to better understand the current supply chain crisis. We are working to identify solutions to current pressing problems in order to make the global system more resilient in the future. We are collaborating closely with inter-agency groups focussed on medicines procurement to ensure our analytical work is strongly embedded in the policy context.

Key:

- 1,3 social distancing measures have impacted manufacturing

- 2,5,7 Export bans have impacted the flow of goods across borders.

- 2,5,7,9 Logistical problems and disruptions have disrupted transportation of goods.

- 4,6 delays at ports

Scoping the extent of the problem

For medicines financed and/or procured by global agencies (including medicines for HIV/AIDS, TB, and malaria, or contraception) there are multiple efforts underway by agencies such as the Global Fund, USAID, and Global Drug Facility to manage global supply chain risks from COVID-19. However, for essential medicines which are procured by countries using domestic resources, there is relatively little in terms of globally coordinated efforts to understand and mitigate shortages.

In order to understand the extent and nature of the problem, we are looking at non-COVID products that fall into the category of very essential medicines[i], and carrying out a rapid assessment and analysis of primary and secondary data–including trade data, retail level information, wholesaler surveys, informal feedback from our professional network of heads of central medical stores and supplies across LMICs, and the information-rich IQVIA dataset. We are also looking at which products and countries are most likely to be impacted, how potential shortage situations are likely to evolve, and what the major drivers are of these challenges. While the WHO’s medicine shortage reporting system is able to track shortages that occur in real time, our system aims to catch problems, before they result in a shortage of supply. Which would give time to find alternative sources of drugs at risk, and that can be maintained after the current crisis is over.

We have consulted with WHO and other agencies involved in the essential medicines supply chains and, backed by analysis and stakeholder feedback, our policy proposals aim to help mitigate such shortages, reducing the risks from future crises, whilst also helping improve regulation and competition. We will make policy actions which will draw on existing best practice and be informed by the nature of shortages. Actions may include encouraging companies to register in sub-Saharan Africa, encouraging regulators to provide fast-tracked registration of quality-assured generic manufacturers, sourcing from/enabling high-quality regional manufacturers, whilst maintaining a focus on quality when supplier switching happens. Such policy changes, if implemented, could result in a healthier market for generic medicines, with better quality and more competition resulting in better prices and greater resilience.

Our system aims to catch problems, before they result in a shortage of supply. Which would give time to find alternative sources of drugs at risk, and that can be maintained after the current crisis is over.

What we are currently doing

Product short list

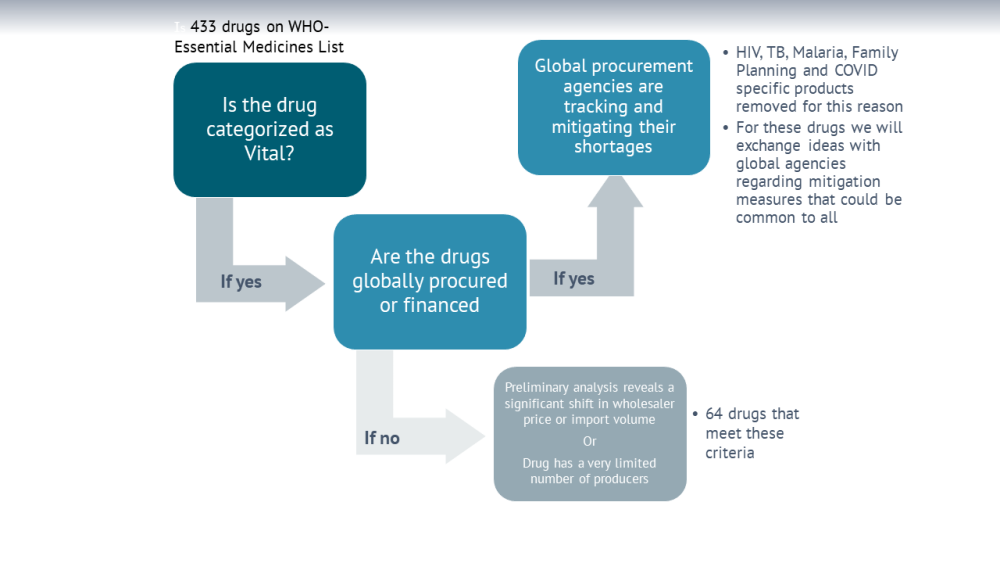

To focus and streamline our efforts, we have shortlisted 64 products from the WHO essential medicines list. We used three criteria for shortlisting:

- Essential medicines which are categorized as vital (as per V/E/N classification);

- Medicines which have been more frequently in global/regional shortages in the past;

- Medicines where preliminary analysis of import/export data shows significant fluctuations in price or volume.

We excluded medicines financed and/or procured by global agencies, and focus mostly on essential medicines which are procured by countries using domestic resources.

We are now analysing these products more closely using or creating five different data sets: disruptive events in the supply chain; trade and flow data; wholesale data; retail pharmacy data; and data from a specifically administered survey to identify shortages. Below we outline these five data sets in more detail.

Dataset 1: Tracking disruptive events in the supply chain

By combining publicly available data sources such as the World Trade Organization’s COVID-19 trade restrictions dataset and air and seaport status updates from global freight forwarders with a rigorous review of news reports, we are building a dataset that will track transport difficulty. This dataset will include routes and ports used to ship drugs, export restrictions of essential medicines, and manufacturing difficulties caused either by lockdowns or an inability to access materials.

Dataset 2: Trade and flows data

We are analysing Indian import and export data; World Trade data; and import data from Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia from 2017 to present day to identify drugs that have seen statistically significant reductions in trade. Work to date shows that there was a 30 percent reduction in exports from India to sub-Saharan Africa in March and April 2020. While data from May suggests that exports have return to almost pre-COVID levels, they may need to increase further to account for the earlier shortfall. We are also utilizing trade data to estimate the degree a country’s of dependence on India, China, or specific geographical regions for sourcing.

Dataset 3: Wholesaler data

We are using IQVIA data panels to identify shortages in drugs. Using information on known shortages in Germany as well as other countries, such as Canada, we are building a model which will use machine learning to identify shortages in the country for which they have good data. Preliminary modelling suggests that more than 80 percent of shortages can be spotted, in some cases months before the shortage reaches pharmacies. Once we have wholesaler and public sector survey data, we can train the model on known shortages in low-income countries, further improving the model.

Dataset 4: Select retail data

We are working with Maisha Meds, mPharma and other groups with retail pharmacy data platforms to identify changes in sales volume, stock, and price of different drugs. Maisha Meds has developed an online dashboard for tracking changes in the market.

Dataset 5: Wholesaler survey

Finally, we will soon be sending out a survey to a large number of private wholesalers and central medical stores in sub-Saharan Africa to learn where there are drug shortages and how the supply chain has changed in recent months.

Table 1. Data Sources

| Wholesaler survey | Select wholesaler panels and product registration data | Select retail panels | Trade & flows data | Event risk data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Private wholesalers: Will undertake with support of IQVIA

Public sector supply agencies: Purpose driven sampling of 4-5 government supply agencies |

IQVIA proprietary data | Data from Maisha Meds, mPharma and other retail data platforms | India export, Kenya, Zambia and Uganda import data | World Trade Organization’s COVID-19 trade restrictions dataset and air and seaport status updates from global freight forwarders, review of news reports |

Planned Research Outputs

Combining and linking these five data sources will enable us to understand which products are at most risk, and why. In cases where disruptions have impacted supply chains, we can track this by first seeing the event; then looking at impacts on trade, retail, and wholesaler data; and finally in how it impacts stocks on the ground in our survey. This will not only allow us to understand what’s at risk now, but it will also build understanding of the weak points in the global supply chain, so in future crises we can know what will happen if port close in India or factories stop production in China.

In some instances, we may be able to detect shortages in advance of when they occur so that wholesalers and distributors have time to respond. We will continue to share these updates with wholesalers and government purchasers who are part of our survey panel. We also plan to release a paper in September that will detail all these risks and a methodology for tracking future crises, combined with possible policy options. We will also propose detailed policy solutions for the blockages we have identified and examine them based on feasibility and impact, in the hope we can use the lessons from this crisis to build a global drug supply chain that is more robust and a marketplace for commodities that works better for the poorest.

Stay tuned for updates on our work, see here for our COVID-19 work, and sign up for our newsletter here.

[i] Vital--Drugs which are potentially lifesaving or which are considered the drug of choice or ‘first line’ items in their respective therapeutic categories

Essential-Drugs which are effective against less severe, but nevertheless significant forms of illnesses, or which provide important ‘back-up’ for vital items. They include ‘second line’ items.

Necessary -drugs is used for minor, or self-limiting illnesses or have useful alternative therapy

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.