Recommended

WORKING PAPERS

A recent report by the Center for Universal Education at Brookings suggests that private school chains may prove to be valuable supplements to public education. Funders seem to agree: school chains are a popular investment for Silicon Valley philanthropists and development finance institutions (DFIs) alike.

But donors looking for scale should think twice before placing all bets on private school chains. Their market share in developing countries is small and growing slowly, and few have scaled to reach substantial numbers of students. There are a couple of exceptions: BRAC in Bangladesh and The Citizens Foundation (TCF) in Pakistan both educate more than 200,000 kids. The vast majority of private schools, however, are not part of a chain. They’re run by individual proprietors, otherwise known as “mom n’ pop shops.”

Whilst there are examples of chains wielding positive influence beyond their own schools, they receive a disproportionate amount of funding and airtime. That’s fine for smaller funders looking for a tangible return on their investment. But the big investors, foundations, and DFIs who care about scale should get serious about how to reach the 120+ million kids enrolled in mom n’ pop shops. That’s the market that has already scaled. That’s where any real private-sector effect is going to come from.

School chains are a popular investment

Philanthropists like private school chains: There are the American billionaires who fund charter school chains, the British billionaires who fund academy chains, the Silicon Valley billionaires who fund school chains in developing countries. They are attracted to the single “investible” entity in which they can take an equity stake or lend to. They like the entrepreneurialism, the innovative approaches and the potential for scale they see in chains. And it’s not just philanthropists: DFIs also like chains. Eighty percent of the International Finance Corporation’s investments in education provision projects between 2011-2015 were in school chains and three of CDC’s five education investments between 2013 and 2017 were in Bridge International Academies (twice) and GEMS’ low-cost brand Dream Schools.

We like them too. We both used to work for one. Between us, we’ve visited and been inspired by schools run by chains in more than a dozen countries. Some of the best schools we’ve seen anywhere in the world have been run by school chains like PEAS in Uganda, TCF in Pakistan, and Spark Schools in South Africa. Children who have the good fortune to attend these schools are probably going to get a better education than their (generally poorer) peers who attend government schools.

The vast majority of school chains are much smaller than the smallest unit of public sector school administration

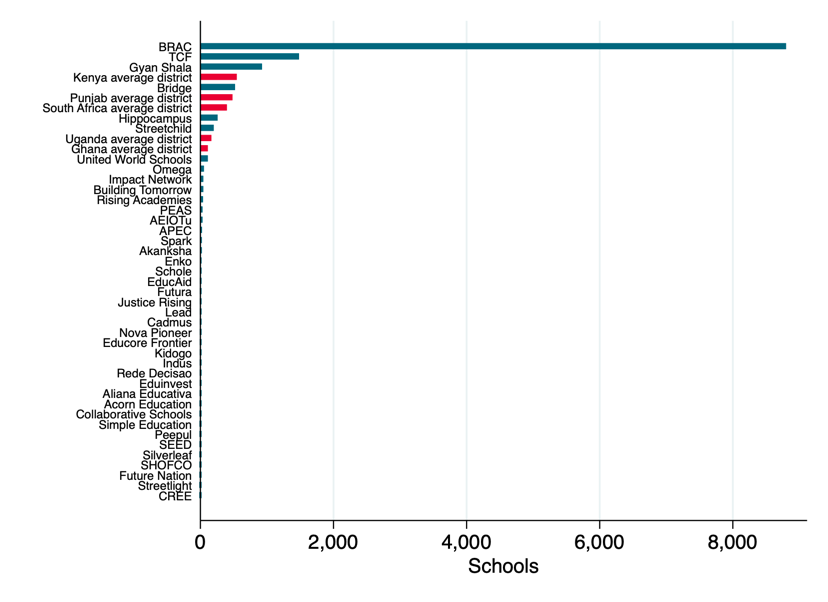

The Global Schools Forum (GSF) is a club for private school chains in developing countries. (Disclosure: one of us, Susannah, was part of the founding board of the Global Schools Forum.) It has 40 members who run about 13,000 schools between them. Most of these schools—9,000—are run by one member, BRAC. We analysed publicly available GSF data and compared their market share with typical public sector operating units (normally a district) in various developing countries.

Unsurprisingly, school chains are dwarfed by government schools. Figure 1 compares GSF chains with the average size of school districts in South Africa, Punjab (Pakistan), Kenya, and Uganda. The median GSF member runs 10 schools. Only six GSF chains can compete in size with the average school district in these countries. And there are hundreds of those districts in every country.

Figure 1. Very few chains are larger than the average government school district.

Source for data: Global Schools Forum and Government websites

Chains are small and they are not growing fast

The GSF chains aren’t very big at the moment, but maybe they’re a good investment because they’ll grow? We don’t have a crystal ball but we can look at how fast chains have grown in the past. The median GSF member is seven years old and has grown by 1.6 schools each year. This is skewed by some very large chains that grow fast (BRAC has grown at an average of 259 schools per year; TCF at 62 schools) and, at the other end, by chains that have been around for a while but never grew beyond their initial one or two schools. By comparison, in India alone the overall number of private schools grew by over 15,000 per year between 2011 and 2016 (Kingdon 2017).

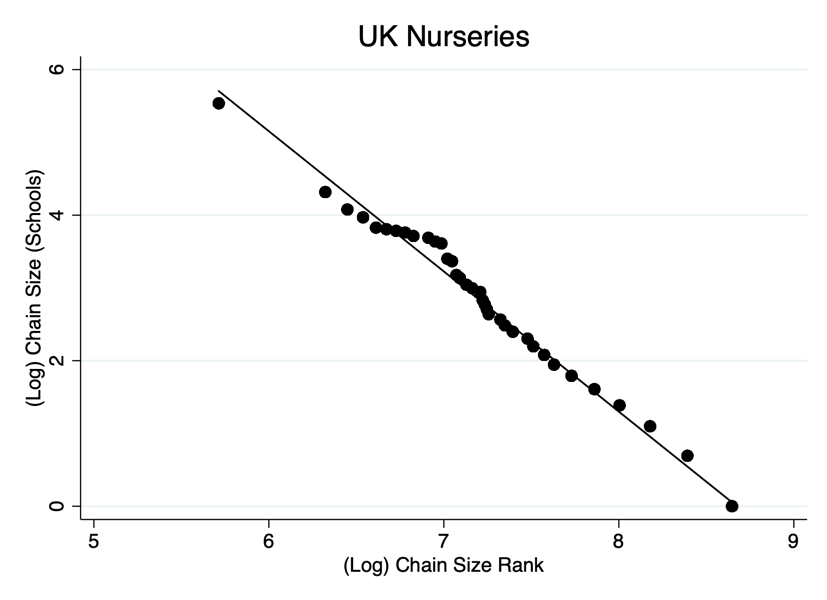

We can also look at chain size in more developed markets. The market for preschool in the UK is mostly private. Here, 60 percent of schools are part of a chain, but the median chain size is still only around five schools. For both UK academy schools and US charter schools, less than one in four are part of a chain, and the median chain has four schools. So even in healthy, developed markets with good rule of law and good access to credit, land, and skilled labour, very few chains actually grow very big. That’s the same in developing countries, according to a study by IPA of the private pre-school market in four African cities. It found that more than 80 percent of private schools in Accra, Lagos, Johannesburg, and Nairobi are mom n’ pop shops. And of the 20 percent that are in a chain, the median chain has three or four schools.

Figure 2. In most systems, the median number of schools in chains is very small and the percentage of schools that are part of a chain is also small.

Sources: Data for UK preschools is from daynurseries.co.uk. For US charter schools from CREDO. The mean chain size is reported rather than the median for US charters. Data for UK academies is from gov.uk. For India is from Gray Matters Capital. For Chile from datos.mineduc.cl. For Nairobi from IPA (Mukuru) and CapPlus. For Kampala from CapPlus. For Lagos and Accra, from IPA.

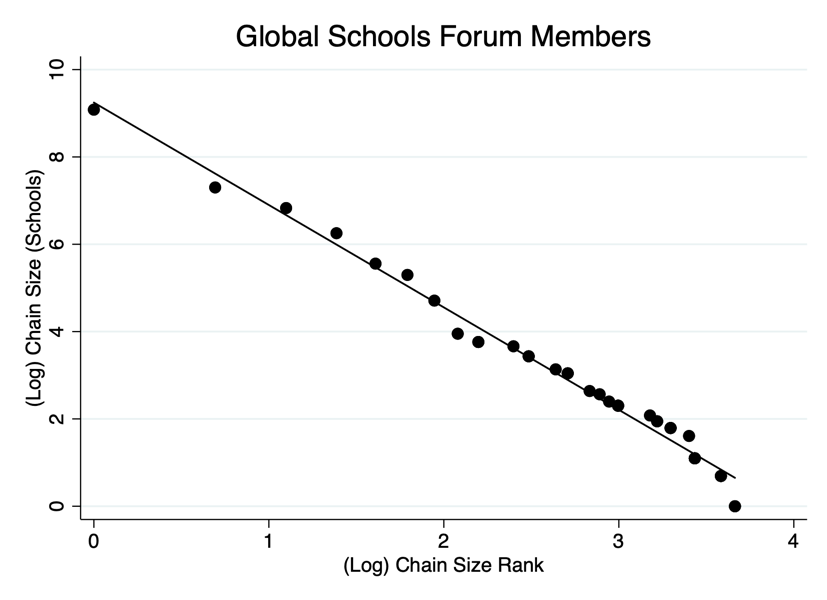

Going beyond average size, we can also look at the full distribution of chain sizes, to see to what extent that distribution is ‘normal.’ Economists have extensively documented the existence of “power laws” in the distribution of firms and cities. Across time and space, there is a remarkable empirical regularity in the size distribution of firms and cities, with just a few very large units and a long tail of smaller ones. Graphically, this can be seen by plotting the logarithm of a unit’s rank against the logarithm of its absolute size. We see the exact same pattern for both UK preschools, and for GSF members. The precise mechanism behind this distribution is unclear, but it is consistent with the growth of any individual unit being as good as random. All of this gives us no reason to believe that there will ever be more than a few very big global chains.

Figure 3. School chains follow a “power law.”

Sources: Data for Global Schools Forum is from globalschoolsforum.org. Data for UK Preschools is from daynurseries.co.uk

It’s not clear whether school chains are outperforming the mom n’ pops on quality, efficiency, or consistency

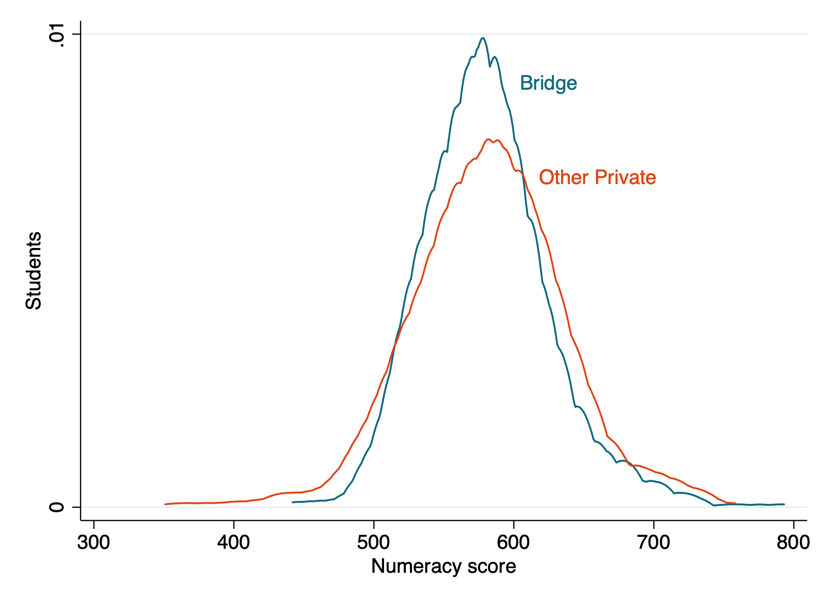

Scale may not be the only holy grail if school chains are producing better results for poor children at a sustainable cost. We don’t know much about whether chains outperform mom n’ pop shops in test scores, since very few chains have undergone rigorous evaluations comparing them with mom n’ pop schools. But for those that have, there is no indication of consistently better results from chain schools.

PEAS schools in Uganda perform better than other private schools in terms of value-added test scores (Crawfurd, 2017). A previous study by EPRC that matched PEAS students with those in government and private schools on observable characteristics suggests PEAS students and other private school students had similar test score performance. Rising Academies perform significantly better than other private schools in Sierra Leone in both reading and maths (Johnson and Hsieh, 2019). In Lagos, Nigeria, Bridge schools perform better than similarly priced local private schools in reading, but no better in mathematics (Crawfurd and Lipcan, 2018). Franchises in Chile get better results than independent private schools (Elacqua, Contreras, Salazar & Santos, 2011), US charters in chains do only very slightly better (CREDO 2017), and in the UK, academy chains do no better in aggregate than government schools (Andrews 2017).

So their performance on test scores is not conclusive, but another attractive feature of private school chains is the back office. In theory, the support provided by functions like curriculum development, teacher training, finance, and so on provide better efficiency and more consistent quality. We don’t have enough data to say whether the back office is efficient financially—school chains don’t tend to be transparent about their costs and sustainability pathway. (We do know that external investment is subsidising Bridge International Academies—one of the larger chains—at around $120 per child per year, in addition to the fees paid by parents, indicating it is a long way from being a sustainable business.)

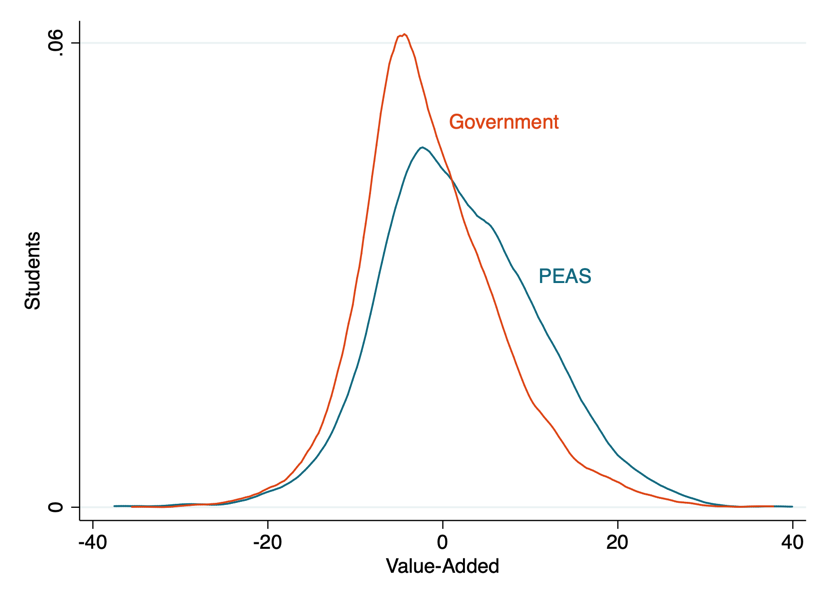

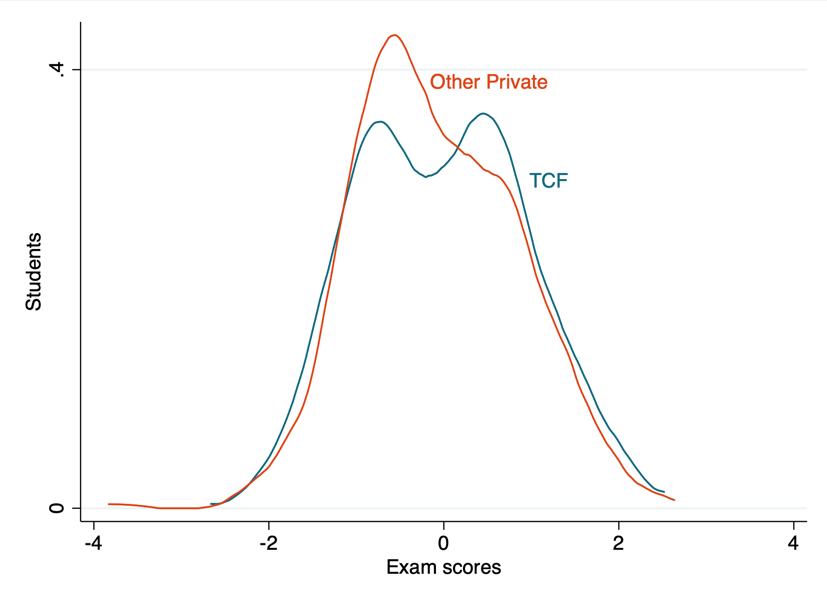

Nor is it clear that the back office delivers greater consistency. Figure 4 compares the range of performance of Bridge, PEAS, and TCF schools with other schools in Lagos, Uganda, and Punjab, respectively. Chains have at least as much variation in quality as individual private schools or government schools.

Figure 4. Chains have just as much variation in quality as any other school.

Source: Data for Bridge from Crawfurd and Lipcan (2018), for PEAS from Crawfurd (2017), and for TCF from Crawfurd (2018)

School chains can be good citizens and good partners to government

Most school chains say they want to support the government. While it’s difficult to see what a chain running two or three private schools can teach the government given the size and complexity of public education systems, it’s a laudable aspiration and one that GSF is skilfully supporting. And some chains do indeed operate as good citizens and in close partnership with government.

Rising Academies in Sierra Leone, for example, is collaborating with the Ministry of Education to test different parts of its model in 25 government schools. PEAS in Uganda is supporting the government to inspect and improve struggling secondary schools in rural areas. In Zambia, PEAS exclusively enrols children whose primary school leaving grades make them ineligible for government secondary school. TCF is the largest private sector employer of women in Pakistan and holds influential roles in key government bodies and commissions.

On the other hand, some chains have flouted local legislation and come into conflict with their government hosts. Bridge International Academies was ordered by the Minister of Education to close its 63 schools in Uganda after it failed to meet regulatory standards. In Liberia, an independent evaluation of the government-led Partnership Schools for Liberia found that Bridge expelled thousands of pupils and pushed under-performing teachers out into other government schools. In other words, the very opposite of positive systemic impact.

Donors should look beyond the usual suspects and think harder about how to engage with the majority of the market that is sole proprietors

School chains have a role to play in education systems. At least in theory, they can act as exemplars of good practice, they can experiment with new pedagogies and technologies, and they can provide support to government through advisory groups or specific programs. For small donors who want to feel close to their grants and investments they are probably a good bet.

But the data suggest that school chains are not, and will not become, a substantial component of public education systems and will be peripheral to solving the twin challenges of getting kids into school and getting them learning. In contrast, tens of millions of kids are enrolled in mom n’ pop schools across the developing world—this is a sector that has already scaled. Despite this, it does not attract significant donor interest: presumably it’s more difficult to find ways to “invest” in lots of small schools rather than the ease of conducting due diligence over a mother ship for a chain of schools.

That’s not really good enough. Donors should try harder to find ways to engage with the mom n’ pop market. There are lessons from a range of programs to draw on: IDP Foundation’s work with low-cost schools in Ghana, a massive effort by DFID to support mom n’ pop schools in Lagos, or the Punjab Education Foundation’s decades of experience in Pakistan. There is also rigorous research to learn from: 15 years of research on private schools by Andrabi et al. in Pakistan, a seminal study on vouchers for private schools in India, and much more.

USAID has recently taken a first step, launching a $40 million request for proposals to support the sector. GSF is now working with intermediary organizations who provide services to the mom n’ pop sector in effort to reach that market. It’s time for the DFIs and Silicon Valley foundations to move beyond easy grants or equity investments to international private school chains and follow suit (and, of course, evaluate their efforts!).

Correction: One of the figure labels previously misidentified Punjab, Pakistan as Punjab, India. We regret the error.

The authors would like it to be noted that this is the right version of the blog’s title song.

With thanks to Rita Perakis for her comments on this blog.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.