This blog post also appeared on the World Bank’s Education for Global Development blog.

A few months ago, a team of education specialists from the World Bank met with the dynamic education minister of a large country. Since taking office, the minister has wanted to transform teacher performance in schools. We were asked: were teacher pay for performance (PFP) schemes, where teachers are rewarded for better performance, the way to go? To the minister, this seemed to be an important option for injecting energy into the country’s teaching profession and motivating better performance. Our team’s conditional “perhaps, but possibly not” answer was not very inspiring.

Many of us have, in some shape or form, been asked by education clients about PFP. And so, we embarked on a comprehensive review of the literature on teacher PFP in low and middle-income countries to help answer the big question—does it really work? You can read a summary here.

What did we find?

Three surprising findings:

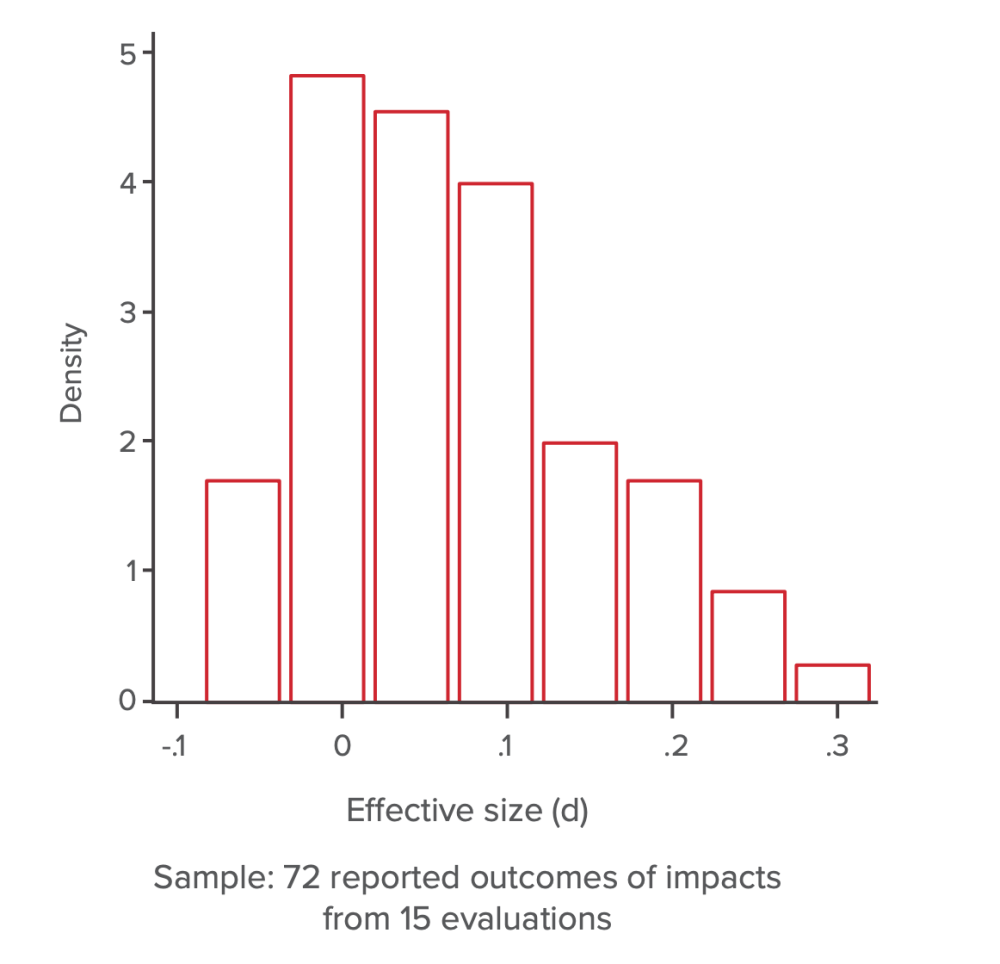

Only a few teacher PFP programs have improved student learning in low and middle-income countries; most have not. There is a lot of variation in effect sizes: across programs, effect sizes range from -0.08 standard deviation (SD) units to 0.32 SD units increase in student test scores. About 50 percent of programs report an effect size of 0.06 SD increase. This is unimpressive—the median effect size on learning across education impact evaluations in low- and middle-income countries is about a 0.1 SD increase.

Most teacher PFP programs do not improve student learning

Adverse, unintended effects such as cheating are non-trivial. Twenty percent of PFP programs reported adverse effects such as cheating or teachers teaching to the test during implementation.

Sustainability has been difficult. Only 33 percent of evaluated teacher PFP programs in low- and middle-income countries were sustained beyond the evaluation period (Indonesia, Zambia, Chile, Uruguay, and Punjab, Pakistan) and only one of these showed positive and significant impacts on student achievement (Chile).

How to do PFPs right

Often, however, PFP programs are attractive to policymakers in low- and middle-income countries—they don’t have to involve fundamental changes to teacher pay scales (as many other career-based incentives do) and can be abandoned relatively easily. So, how can we respond to governments when asked about PFP? We suggest following a three-step decision guide based on our recent review:

Step 1: Are the right preconditions in place?

Technical requirements, resources, and political will are three necessary (but not sufficient) pre-conditions for teacher PFP programs to be successful. Technical requirements include having a capable bureaucracy and reliable data systems that help identify effective and ineffective teachers. Without that capacity, PFP programs are doomed from the start. Teacher PFP programs are also expensive, with costs including not just the incentives, but the setting up and maintenance of the entire accountability framework for monitoring and evaluating. Finally, the importance of political will and teacher buy-in cannot be overemphasized. In Mexico, poor teacher buy-in terminated an ambitious teacher reform program before it could reap benefits. In contrast, in Chile, an initial trial period allowed teachers to opt-in/out of the program, thereby providing choice versus blanket enforcement of policy. While there are surveys showing teacher support for PFP (in India and Tanzania, for example), those systems have not managed to sustain PFP at scale.

Step 2: What design and implementation features are important?

Four key issues are important to consider here: (1) who gets rewarded; (2) what gets rewarded; (3) how do rewards get distributed; and (4) what form to give rewards in and how much? We need a clear understanding of the political and cultural landscape when advising governments on the kind of incentive or reward that will be most feasible when implementing teacher PFP. On what to reward, the evidence is clear: have multiple measures of teacher performance versus only one. How should rewards be distributed? Although there is limited work here, one study suggests that in a loss-aversion model, whereby a bonus is given to all teachers upfront, but taken away from ineffective teachers at the end of the year, student performance improved. Regarding the form to give rewards in, this could be monetary or in-kind, but the amount should be sizeable to motivate better performance. There is no clear guidance from the literature on the right size, so governments will have to balance fiscal feasibility with an attractive bonus size.

Source: Breeding, Béteille, and Evans 2021

Step 3: What could derail performance pay interventions?

Common implementation challenges include cheating, teaching to the test, or test manipulation by excluding poorly performing students. For group-based incentives, free-riding could create problems. To help reduce these risks, it is crucial to have multiple checks to ensure tests are implemented with fidelity, and accountability systems that routinely observe teacher classroom behavior and practice. In Andhra Pradesh, for example, cheating was limited by ensuring tests were conducted by external teams of five evaluators in each school, the identity of the students taking the test was verified, and grading was done at a supervised central location at the end of each test day.

Most PFP programs have not shown promise in improving teacher performance. Often, implementation challenges compromise such programs. Following the steps outlined above could help determine whether PFP programs will work in a given context.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.