Recommended

Note: These remarks were prepared for the Global Development Network (GDN) 2019 Conference, held in Bonn, Germany on October 23-24, 2019.

A very positive aspect of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals is that the days when development was seen as a mechanical convergence to the per capita income levels of the advanced economies are long gone. There are two reasons for this: firstly, development is now associated with multiple dimensions and not just income; and secondly, since no country has achieved all the goals, all countries have work to do and no one is a position to serve as the model on all fronts for everyone else.

Achieving the SDGs requires global collective action. Country-level actions are important, but the most relevant challenges can only be achieved through cooperation. Eradicating certain diseases and reducing carbon emissions, for example, require coordination in the global arena.

SDGs go beyond the economic convergence to the living standards of the advanced economies. This implies that no specific development experience serves as a model. Different countries have made progress in different dimensions, but every country has challenges ahead. SDGs are more about collective aspirations to higher (and new) standards, rather than convergence towards a particular level of income. In the context of the SDGs, progress is not defined in relation to others, but in terms of what each country needs to do. This is a race to the top of the development ladder and all countries need to move up.

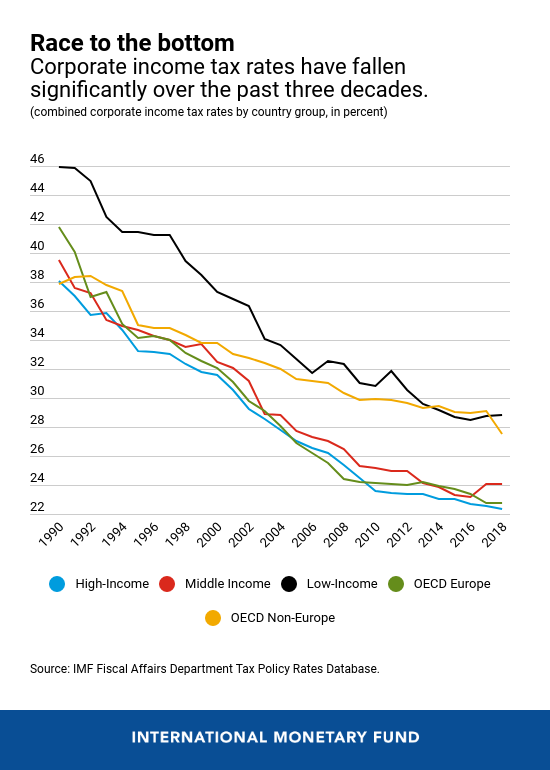

But the race to the top can be severely undermined by another race that is also taking place: The race to the bottom when it comes to corporate income taxation. With the goal of stimulating economic growth, a large number countries have reduced corporate income taxes significantly (see chart below). This was, for example, the case of the U.S. which lowered the corporate rate to 21 percent in the December 2017 tax reform law. But many others have followed this path, including a proposal by the government in India that would reduce the rate to 25 percent. In Latin America, the Colombian Congress is now discussing a bill with the same approach. The main message is that, because of competition, if countries do not lower taxes on corporate profits, businesses will move elsewhere, reducing economic growth.

This is a contradiction in terms: there cannot be progress in terms of the SDGs–where collective action is crucial, and provision of public goods indispensable–without a strong engagement on the part of the government. Without state capacity the ladder of development breaks down.

I firmly believe that achieving the SDGs is very unlikely if governments do not have the fiscal capacity that is required. Moreover, without direct taxation–both of corporations and individuals—it is extremely difficult for countries to raise more revenues as a share of GDP while at the same time reducing income inequality. While countries remain engaged in a race to the bottom in terms of tax policies, the race to the top in terms of development is an aspiration with very limited possibilities of success.

Current trends in terms of corporate income tax rates, for all groups of countries, are well illustrated in Chart 1, which comes from the IMF. This trend–let’s call it a weakening of state capacities—would need to be offset by an upward trend in other forms of taxation. That, unfortunately, is not the case.

Race to the bottom

At the entrance of the IRS building in Washington DC there is a large encryption that says, “Taxes are what we pay for a civilized society.” The SDGs embrace a new concept of civilization, one that is more inclusive and sustainable. If taxes were necessary for the civilizations of the past, they are even more necessary for the civilizations of the future. Broad-based and sustainable development is costly, and it is not possible to get it for free.

Lowering taxes on corporate profits is one problem. However there is also the problem of greater tolerance towards tax avoidance. Take, for example, the evolution of the profits booked by US multinationals in tax havens since 1965. According to Saez and Zucman (2019), the share of foreign profits booked in tax havens has surged from less than 5% in the 1960s to almost 60% today but workers and capital haven't moved to tax havens nearly as much.

Given how crucial tax revenue is to achieving the SDGs, we must fight tax avoidance and evasion, such as offshore shell companies, tax-deductible paper losses, and tax havens.. Tax international cooperation is needed, not international tax competition. This is a particularly serious problem for countries that start from a position of disadvantage in terms of low tax revenues–which in general also means low levels of development. For them, moving up is almost impossible as they do not have the capacity for climbing the development ladder.

And this is not just about corporations. Taxing the rich is crucial in order to reduce inequality.

Philanthropy is not a substitute for the role of the state, it is a complement.

Science and research

The global and inter-linked nature of the SDGs calls for coordination and collective action. In addition, the conflicting nature of some of the goals–or the excessive costs associated with them–require research to ameliorate tensions and trade-offs between goals. Also, research can provide less expensive ways to accelerate progress in multiple areas in which today’s technologies do not assure the necessary outcomes. This means that the development agenda calls for an active involvement of the scientific and research community.

Speeding up the process of producing major innovations in multiple areas, such as health and the environment, is indispensable. Otherwise, the SDGs will remain elusive and hard to attain. Good intentions will not get us there. Adequate research and well-funded interventions will.

Climate change science offers some very good examples. Curbing emissions is a crucial component of the 2030 development action plan, which includes the Paris Agreement. Without actions to reduce global warming, development is severely compromised. Science has already explained the dangers associated with the increase in temperatures, including in areas such as health.

Carbon taxes are of great relevance in this context. A few countries are trying to meet the targets by introducing taxes on fossil fuels (or reducing subsidies on gasoline and diesel), but more often than not this has become the source of great unrest, as the episodes in France and Ecuador reveal.

This suggests that there are conflicts associated with achieving SDGs: one the one hand it is crucial to reduce emissions, on the other individuals do not wat to see their living standards affected by higher costs of energy. Also, political stability and conflict resolution are part of the SDGs, so achieving one goal at the expense of other is not ideal. These are good examples of the tensions that arise in the process of development in general, and in achieving the SDGs in particular.

Science can be extremely helpful in reducing the burden associated with carbon taxes, in areas such as the innovation in low-carbon technologies, or a better understanding of the behavioral barriers that constrain our ability to use energy more efficiently. Improving public infrastructure is another way to reduce carbon emissions. Progress has already been made in a number of areas that reduce emission such as electric vehicles and renewable energy. But much more work is needed in order to complement a carbon tax, and make it more effective and easier to adopt.

A good example of the pending tasks are the innovations that are needed in order to make agricultural and industrial production more sustainable. As Columbia University’s Jason Bordoff noted in a recent Wall Street Journal piece, 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions come from agricultural production. Carbon taxes alone are not going to the trick in reducing emissions, unless dramatic changes take place on how we produce and consume food. This is especially true in the case of livestock, which is the leading source of methane emissions in agriculture.

Many developing countries are cutting down forests in order to increase agricultural production, illustrating tensions that can arise when individuals in search of higher incomes and better nutrition engage in unsustainable practices. Agriculture is also a leading driver of land-use change, which accounts for one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions.

A similar problem arises in the production of cement, steel, fuels, chemicals and other industrial products that are essential to construction, infrastructure and manufacturing. As Julio Friedman, also from Columbia, has noted, making these products –which are crucial for development-- requires a lot of heat. In fact, the type of heat that emits more carbon dioxide than all the world’s cars and planes.

The main point is that subsidizing renewables, setting efficiency standards or even pricing carbon, is not enough. The solution is innovation. Only science can help find the innovations that would reduce the climate change impacts that will arise with higher incomes and consumption levels that come with the attainment of the SDGs. One option is carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS), which is still in its infancy.

These are examples of why the development agenda truly depends on research and innovation, which cannot be provided by the market alone. Governments need to step in, and that requires fiscal capacity. In the US, for example, tax credits were essential for the initial development of solar and wind energy. The same is true of the new technologies that would ease the difficult trade-offs that we are confronting today.

Research in the social sciences also has a role. Development challenges are no longer seen as wholly economic in nature, but also social and ethical. This requires multidisciplinary approaches that call on sociology, anthropology, psychology and political science, as well as on economics. For example, if we want to change consumption patterns and habits that are well entrenched, without generating social turmoil, we must turn to behavioral sciences. These are not simple questions and the answers require input that is multidisciplinary and that can inform political decisions. In democracies, enforceable decisions require the consent and support of the majority. How to obtain that support is absolutely crucial, especially when there are upfront costs and long-term gains.

To conclude

The 2030 Agenda formulates goals and implies challenges for all countries. In those cases where human development has advanced the most, there are serious issues of sustainability given the effects that higher standards of living have implied for the earth's climate and its ecosystems. At the same time, improving economic wellbeing in those countries with a small environmental footprint should not be delayed. In both contexts the government has to play a crucial role in order to provide the public goods and resolve the market failures that can increase living standards while reducing the effects of climate change.

This requires greater state capacity, not less. That is why the level of ambition of the 2030 Agenda is completely inconsistent with the race to the bottom in income taxation. The debate about taxes cannot be centered around competition and economic efficiency, it has to take place in the broader perspective of the development agenda.

Finally, science and research–which are an example of the need of government resources—are necessary to provide less expensive ways to achieve the SDGs, while at the same time providing input to politicians and policymakers so that the decisions that need to be taken are acceptable and supported by the majority of the electorate. Otherwise, the SDGs will win in the normative world, but lose at the polls.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: International Monetary Fund