As coronavirus sweeps across the globe, countries have shuttered school systems in an effort to slow its spread. UNESCO has done an excellent job of tracking global school closures. To build upon this effort, we’ve created a new database that includes more detail about the closures and other support countries are providing whilst schools are closed. We’re updating the database several times daily, and have sourced from news articles, ministry of education websites, and official social media pages. We welcome any and all feedback to lcrawfurd@cgdev.org, in particular any country details we are missing or have coded incorrectly.

Using our database, here’s what we found about the scale and timing of school closures, as well as how countries are adjusting to distance learning.

School closures increased substantially over the past week—even in the absence of confirmed cases

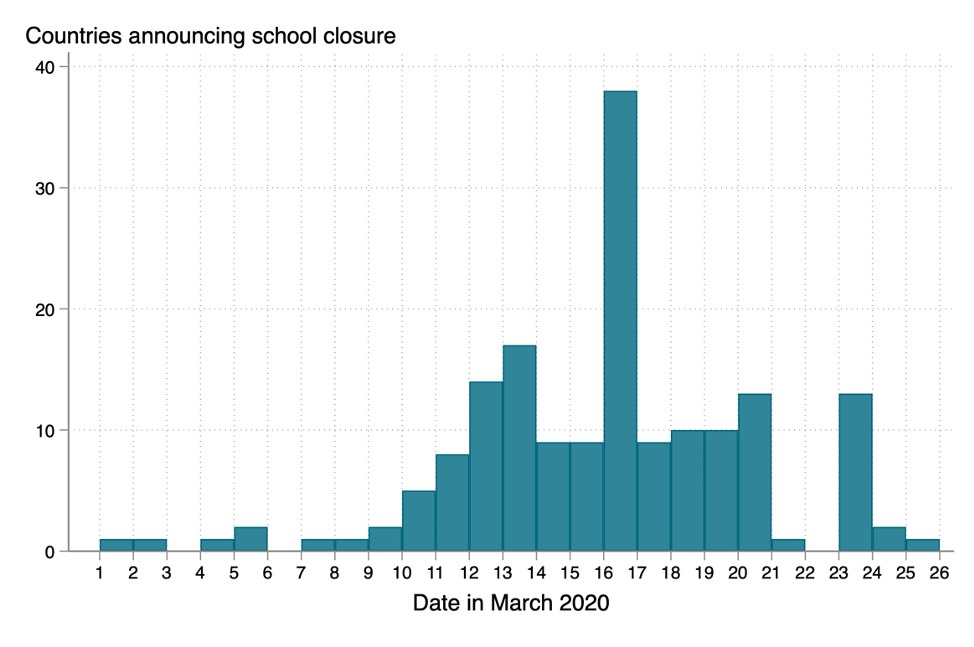

There was a substantial spike in nationwide school closures following the World Health Organization’s designation of a global pandemic on March 11. By March 23, nationwide closures had been announced by 170 countries, with closures accelerating particularly across Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia. According to UNESCO, more than 1.3 billion children—over 80 percent of those enrolled in school across the globe—have seen their schools close.

Figure 1. Global school closures by date

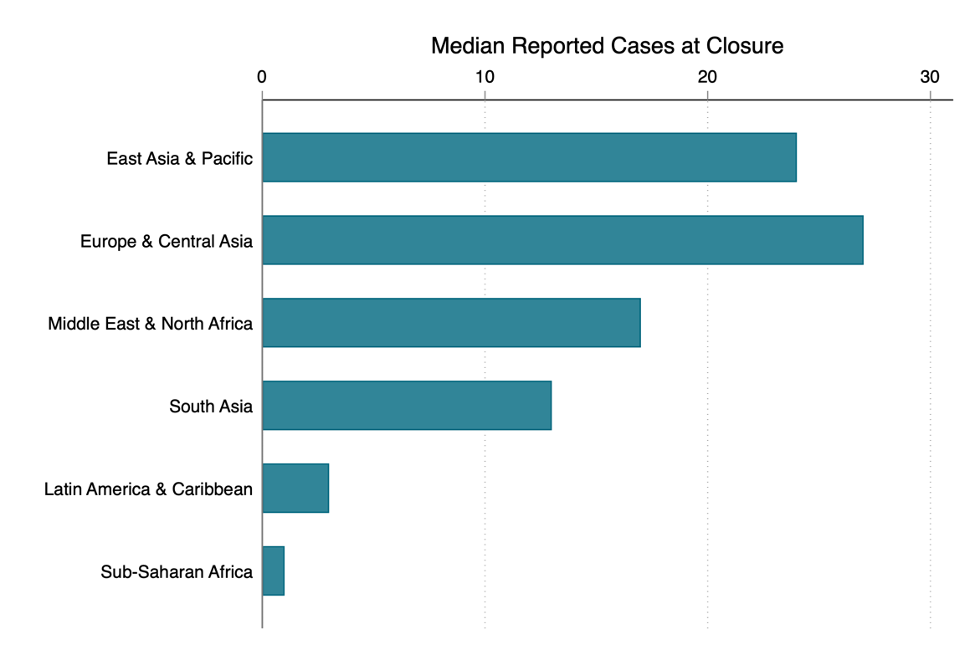

In some countries, school closures are announced before a COVID-19 case is diagnosed

One trend that emerged this week is pre-emptive closures, before any cases have even been reported. Twenty-seven countries closed schools with no confirmed cases, and another 34 countries closed schools with two or fewer confirmed cases. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa seem particularly inclined to take action early—more than 10 countries have closed down their schools without any reported cases.

Figure 2. Median number of reported COVID-19 cases at school closure, by region

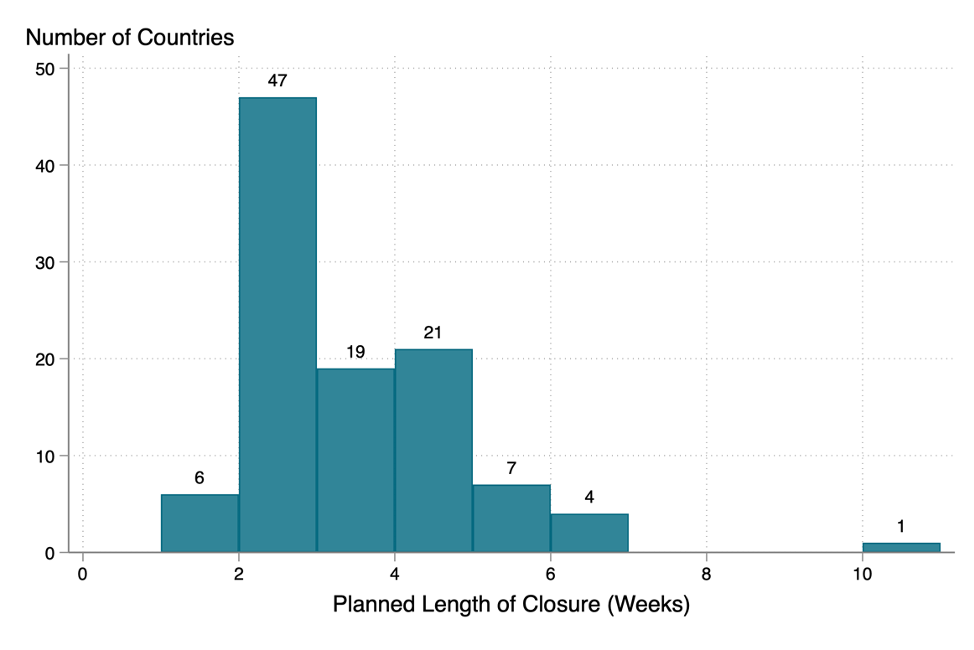

Most countries have announced short-term school closures

Fifty-six countries have closed schools indefinitely, but 73 countries have closed schools for three weeks or less. In many cases this has been simply extensions of pre-planned spring or Easter breaks. It seems optimistic that the situation will have dramatically improved in such a short timeframe.

Figure 3. Length of planned school closures

Note: This figure excludes the 47 countries that closed schools indefinitely.

National exams have been postponed or cancelled in at least 23 countries so far

Cancelled and postponed exams include the West African Secondary School Certificate Examinations (WASSCE) in Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and The Gambia; and the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) in the United Kingdom.

Many countries are attempting to provide distance learning for their students

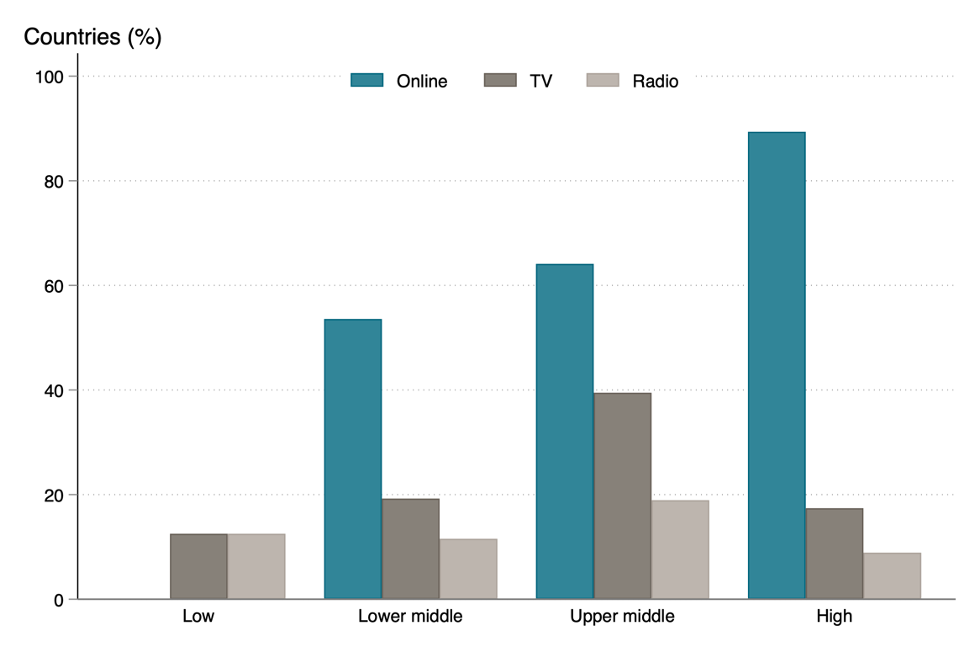

Global concerns about lost learning have kept pace with the increase in school closures. More than 50 percent of countries have announced plans for implementing distance learning—whether it be online, TV, or radio.Twitter hashtags like “#SchoolsNotOut” in Jamaica aim to remind students and families that school closures do not mean the end of learning.

Whether a country has announced plans for distance learning is highly correlated with income. Eighty-five percent of high-income countries have announced plans for distance learning opportunities, compared to just 15 percent of low-income countries. Of the 30+ countries in sub-Saharan Africa to announce mass closures, only 4 (Kenya, Senegal, Seychelles, and South Africa) have announced distance learning plans for primary and secondary education.

Figure 4. Announcement of distance learning measures

There is a great deal of variation in countries’ plans for distance learning

Most countries plan to use online, television, or radio programming to deliver remote lessons. Some, including Angola, Uganda, and Zambia, have planned to send work home with students, and have suggested families and teachers implement “homegrown solutions” for covering the material. It is relatively uncommon for countries to rely solely on direct virtual lessons with teachers; nearly all are encouraging parents to engage in home-based learning activities. Some, like Denmark, are also providing concrete resources to support parents.

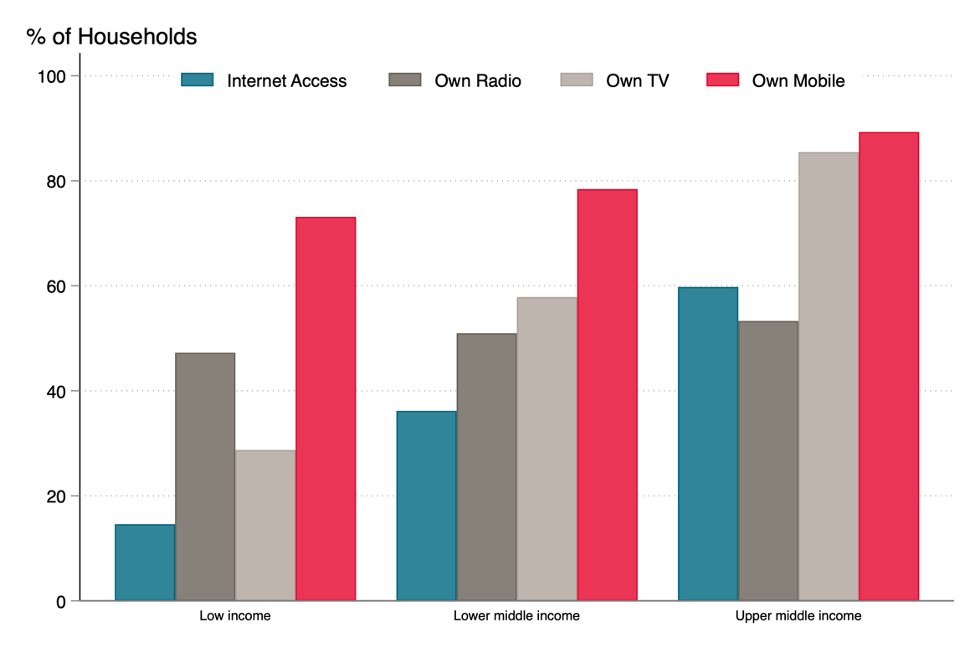

Online learning opportunities are by far the most common—and diverse—solution, with more than 80 countries advertising plans for online instruction of some kind. This may be cause for concern, since many countries that are promoting online learning have rates of internet access under 40 percent (Figure 5). Some, including Cambodia and the Philippines, have made digital learning available through computer or mobile phones. Digital libraries and PDF copies of textbooks are available in many places. For example, Namibia announced grant funding from a foundation to make a digital library widely available through a reading app for students.

Figure 5. Household access to internet, radio, TV, and mobile phone

Source: Data for internet access from globaldatalab.org, for radio, TV, and mobile, from statcompiler.com

There is huge diversity in the content, structure, and quality of online services offered to students. In some cases, ministries of education have simply pointed to existing services such as Google Classroom and Khan Academy. Others are developing their own programming aligned with their national curricula to be available online. Governments are drawing heavily on social media resources including Facebook and YouTube to communicate with and deliver lessons to students and families. Qatar has implemented heavily structured online learning opportunities, including mandating weekly assessments. Armenia is offering an accelerated certificate course for teachers on distance learning to help them prepare—and get credit for—the transition online.

Televised instruction has also been advertised in at least 30 lower-middle and upper-middle income countries. While televised learning opportunities also vary widely, countries using this medium are typically partnering with national media companies and advertise a schedule of planned programming by grade level through social media and other news outlets allowing students to tune in for broadcasts of the lessons relevant for them. For example, Afghanistan recently announced plans for trained teachers to deliver lessons via television and radio programs. In Azerbaijan, students can tune into “Lesson Time” available in Azerbijani or Russian from 10am–4pm each day for all classes.

Thus far, no country is planning to rely solely on radio-based instruction. Sixteen countries have advertised plans to make education programming available over radio and some, like Kenya and Guyana, have made plans for interactive radio programming to deliver the national curriculum on stations throughout the country. Iran has prioritized radio programming in order to reach teachers and students in the most remote areas.

Importantly, very little evidence exists on the effectiveness of any of these efforts. We all have a lot to learn.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.