For all of the horrors that have punctuated the last two hundred years of human history, we have seen some awesomely unprecedented progress in global quality of life. The world has many more people, living much longer and healthier, in massively improved material circumstances than it did two hundred years ago. In a new working paper, I explore a bit of what lies behind that progress and whether it will continue.

The paper presents a simple (and derivative) model of progress based on the interaction between technology, population, and education. Larger populations drive (slow) technology growth, which increases returns to education, which both speeds technology growth and helps retard population expansion. But as the world passes peak population and sees diminishing returns to increasingly high levels of education, this model suggests we are approaching a slowdown in the rate of technological advance. .

I then try to fit the facts to the model. The global population is peaking thanks to a combination of improved health, education and rising incomes that have reduced fertility rates, but also raw population is becoming a less important driver of innovation. Education is plateauing in richer countries (in the US, education rates have levelled since the 1990s: roughly 85 percent of kids graduate from high school, roughly one third graduate from 4-year colleges). And returns to education in terms of technology advance do seem to be declining (one example: there are 25 times the crop researchers in the US compared to 1960, but corn yields have only increased linearly). Overall, Economist Thomas Philippon has looked at past patterns of total factor productivity growth for 23 advanced countries over 129 years and suggests that total factor productivity grows in a pattern that usually looks additive rather than exponential, again suggesting we’re in an era of peak progress.

The paper elaborates on some reasons we’re seeing declining technology returns to education, including a growing distance to the frontier of knowledge and the transactions costs related to the increased necessity of cooperation to reach that frontier (for instance, the average size of the team behind a patentable invention has increased at 17 percent per decade in the US). And it adds some potential factors behind slowing technology advance not directly implied by the model, including that the innovations we want are increasingly the innovations we are bad at producing. Two hundred years of material progress has left us increasingly focused on non-material riches, but we’re not as good at increasing productivity in non-material output. One partial measure is that services now account for two thirds of global GDP (and 80 percent of US GDP) and yet more than 70 percent of US corporate patents are still in manufacturing.

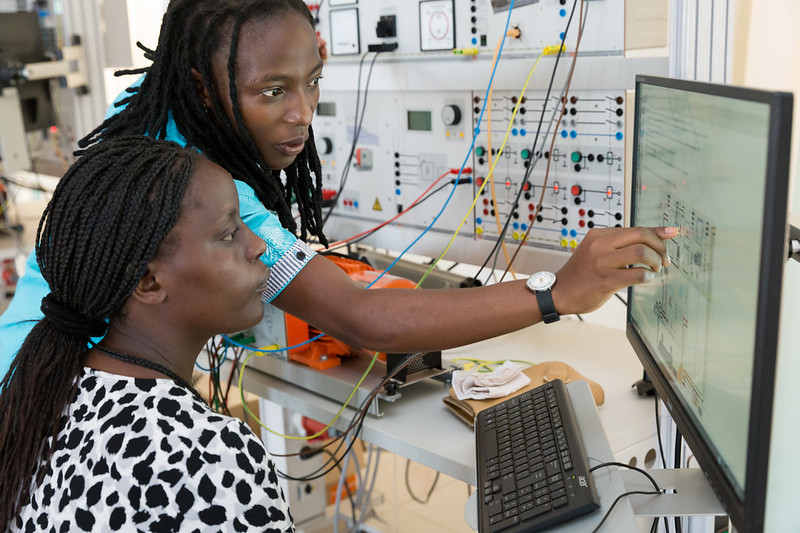

I don’t think this suggests any imminent collapse in global technological advance. Not least, there is an immense amount of wasted innovative capacity around. Children from high-income (top 1 percent) families are 10 times as likely to become patent holders as those from below-median income families. The proportion of US patents that include at least one woman inventor is below 20 percent. The opportunities for a woman born to poor parents in Mali to innovate on the technology frontier is a tiny percentage of that for a man born to rich parents in Silicon Valley. Radically improving equality of opportunity to innovate would create the potential for lots more progress. But still, it appears likely that the rate of progress will eventually slow.

The paper is part of a larger project. I want to write a book about the past and future of human progress: why we might be passing the period of peak change and what comes next. It is a case for the middle ground between the dystopian and utopian visions that dominate pop futurology. On the one side are those who believe we are in inevitable decline: parasitic interlopers on a pristine planet destined to consume our way to catastrophe, fallen from a state of grace occupied by white men in the 1950s, or some combination of both—millenarians of right and left. On the other side are those who argue we’re headed to colonies around distant stars and immortal symbiosis with cyborg hosts—silicon-valley hugging futurists brought up on a diet of Star Trek.

I want to argue that the future is likely to be more prosaic than either of those visions. Nonetheless, it has a considerable beauty of its own. Even with slowing technological progress, and even given the crooked timber out of which humanity is hewn, it seems quite plausible to me that we’ll be on a planet of generations ten billion strong living lives of a quality beyond the dreams of their ancestors. That wouldn’t be a bad place to end up.

With the working title of Slowdown, a book is some way off—possibly an infinite way off. The pitch is in draft, the ‘research’ is 160,000 words of pasted abstracts and semi-random thoughts, I have an at least somewhat skeptical agent and haven’t approached any publishers. But the project is already paying off for me: this summer I spent two wonderful weeks at the Property and Environment Research Center writing a first draft of the paper and receiving incredibly valuable feedback from the people there. Thanks to them and Ranil Dissanayake for much improving the draft, even if it is still surely a work in progress—one that I would love more comments on!

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.