We all know that politics shapes which education policies are adopted, and, therefore, how much learning happens in school. But it turns out that many of our intuitions about how politics shapes education policymaking are wrong. Over the past years, I have been subjecting some of our most common intuitions about politics to empirical tests. Along the way, I learned things I sometimes did not expect—but I came to accept that the data don’t lie.

In a series of blog posts over the next few weeks, I will summarize three key things I have learned about how politics shapes education systems. The first one is this:

The obsession with teacher unions is unwarranted

The conventional wisdom is that countries don’t advance reforms to improve education quality because powerful teacher unions block these reforms. Underlying this argument is the belief that teacher unions have disproportionate influence over education policy choices. This belief, despite its pervasiveness, is based (a) mostly on anecdotal evidence or (b) on systematic evidence from an exceptionally small number of countries, namely the US and, to a lesser extent, India and Mexico.

Studies of US teacher unions have been especially influential in shaping how we think and talk about teacher unions worldwide, with work by Caroline Hoxby and Terry Moe routinely cited in international development reports to support the notion that teacher unions generally (not just in the US) act as powerful vested interests that increase the size and reduce the efficiency of education systems.

It turns out that this influential view is poorly supported by the data—including in the US. The conclusion in Hoxby’s much-cited study that collective bargaining with teachers increases education spending and teacher salaries was due to mistakes in the data she used. Michael Lovenheim fixed these mistakes for three midwestern states in the US and showed that if you apply Hoxby’s methods to the improved dataset, you no longer find effects of collective bargaining on any of the things that Hoxby examined.

In my own work, I gathered data from all 50 states from 1919 to the present and used it to quantify the impact of collective bargaining rights for teachers on personnel and education spending decisions. Like Lovenheim, but with data from all states, I found that the introduction of collective bargaining with teachers had no average effect on student-teacher ratios, teacher salaries, education spending, non-wage education spending, or the probability of being fired during a recession—all things that no-one would question unions try to influence.

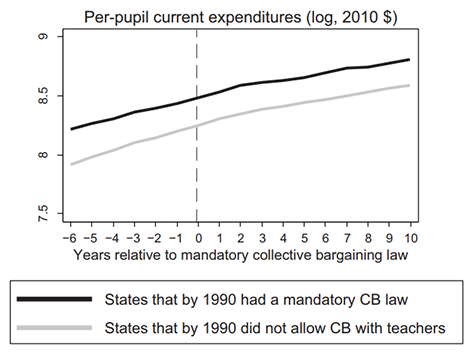

You can see this for yourself in the graph below. The black line shows how per-pupil education expenditures changed among states that have collective bargaining rights for teachers before and after they introduced those rights, and the grey line shows how expenditures changed during the same period in states that did not introduce bargaining rights. If collective bargaining had led to an increase in education spending, we should see a divergence between the black and grey lines after collective bargaining rights were introduced in some states but not others. We don’t see this. And the same holds if we look at student-teacher ratios, teacher salaries, or non-wage education expenditures.

Which brings up the question: Why didn’t collective bargaining and teacher unionization affect the choice of education policies?

In the US, as in the rest of the world, teacher unions are not monolithic: How they are regulated varies, and these regulations affect unions’ ability to influence education policy.

Of special relevance to union power is whether teachers have both collective bargaining rights and the ability to strike. Collective bargaining rights without the ability to go on strike (or without the ability to make credible threats that the union will go on strike if dissatisfied with negotiations) should not enable unions to obtain higher salaries. This is precisely what I find. It is only when teachers have both collective bargaining rights and the ability to go on strike that collective bargaining leads to modest increases in teacher salaries.

As I’ve documented, though, not all US states have collective bargaining rights for teachers, and among those that do, most prohibit teacher strikes and stipulate severe penalties for unions if they go on strike—such as wage losses for teachers that strike and union decertification.

We see this variation around the rest of the world, too: about 60 percent of countries have both collective bargaining rights and strike rights, but 40 percent either have collective bargaining with no strike rights or have no collective bargaining rights at all.

And there are other relevant differences across teacher unions, especially outside the US: some are coopted by a political party or autocratic regime, while others remain politically autonomous. Can we really blame coopted unions for the absence of education reforms? Or should we seek an explanation for the lack of reform by looking at the incentives of the political party or regime that controls these unions?

We need to recognize that unions are not monolithic, that they are regulated in different ways, and that how they are regulated (do they have collective bargaining rights? strike rights? do they have political autonomy?) affects their ability to influence education policy.

The US case also illustrates a broader point about politics in democracies: ceteris paribus rarely holds. When teachers become more organized and active, so do other actors that don’t like them.

In democracies, when one actor becomes organized and demands more power, others who stand to lose from this redistribution of power organize as well to mount a counteroffensive. This leads to a maintenance in the distribution of political power, even if new laws are passed.

This is what I found when I studied the US: teachers suddenly became more organized in the 1960s, but in response, so did business groups and politicians concerned about unions’ empowerment. The struggle between pro- and anti-labor interests led to the introduction of labor laws regulating teacher unions that, on one hand, gave collective bargaining rights to teachers (pro-labor) and at the same time, made it more difficult for teachers to go on strike (anti-labor).

So yes, Hoxby and Moe are correct that if the world moved from having no teacher unions to having teacher unions, and everything else stayed the same—which is what older theories assume—then we would expect the world with unions to adopt education policies that are in line with what unions want. But that “if” rarely holds in the real world.

Policy, at least in democratic settings, is usually the outcome of a bargain between multiple actors with competing interests, and that is why democracies are often prone to maintain the status quo—in education policy and in other areas.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Social media image by John W Iwanski