Recommended

In the Pandemic Fund’s inaugural year—whose first-year performance can determine next year’s fundraising efforts—the Fund has an opportunity to make the case for investment in surveillance in general and a variety of surveillance approaches for pandemic preparedness.

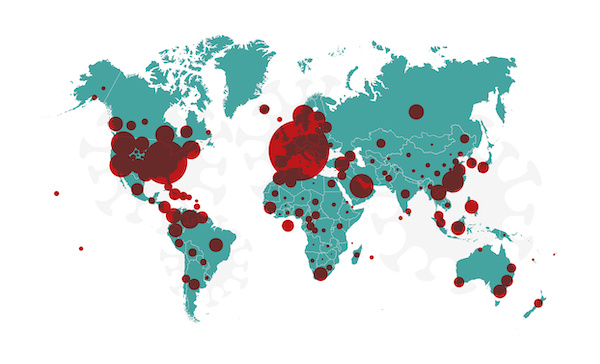

While the term “surveillance” may conjure negative connotations of prying eyes and government overreach, surveillance for pandemic preparedness is not only less sinister, but lifesaving. Common sense dictates that disease surveillance of an epidemic of pandemic potential can trigger local, national, and international actions that can slow the spread and save lives. The Pandemic Fund’s initial focus on surveillance as part of its first call for proposals is therefore welcome and very much needed.

But investing in surveillance writ large or in general is not an investment strategy. Just because you wish to invest in the category of stocks doesn’t mean you can avoid the decision of which stocks to invest in. Similarly, the Pandemic Fund would greatly benefit in helping countries strategically invest in a menu of choices of surveillance approaches, many of which are complementary, and encompassing of laboratory networks and human resources, with surveillance as the broader concept.

In our new policy paper, we share findings from a rapid review and a private convening of experts about the “best buys” of surveillance for pandemic preparedness. Here is what we have learned about what we need to better invest strategically for surveillance:

There is broad agreement that efforts in pandemic preparedness can be strategically guided by an ex ante menu of surveillance interventions that outlines the costs and benefits to help countries make decisions, including through the WHO Mosaic Framework. This framework poses a kind of menu for decision-making that is distinct from the Joint External Evaluation tool (used for compliance with the International Health Regulations (IHR)) for general direction of the topic of surveillance, but the specifics of what kinds of surveillance to do.

Our rapid review of the evidence found that the costs of such surveillance approaches are quite limited, but there is some evidence base for the effectiveness of these programs. For example, sentinel surveillance (monitoring conducted by a smaller group of health workers, that could be generalizable to a larger segment of the population) appears to have slightly more information on costs compared to three other selected surveillance approaches. However, the effectiveness of one surveillance approach compared to another is not well quantified or measured.

With a limited knowledge base, the Pandemic Fund should use evaluation to measure the costs and benefits of surveillance—which will also further the Fund’s own investment case and fundraising efforts. The Fund needs independent and rigorous evaluation ex post of the value and impact of preparedness investments (including for surveillance). In doing so, it should also establish a small set of multidimensional metrics of effectiveness of surveillance systems that not only considers the IHR’s concern about timeliness, but also local needs and demands including flexibility of detecting new pathogens, patient care improvement, and use of epidemiologic data for policy decisions.

Concluding thoughts

Though the estimated minimum financial resources needed to adequately finance the Pandemic Fund are marginal compared to what the US spends on domestic health per day (just 0.001 percent), the outlook for public spending on health is bleak and will require significant political will and cooperation to mobilize and sustain the level of investments needed. This makes it all the more important to invest in what works, or the “best buys” of surveillance for pandemic preparedness, before the next pandemic occurs—likely sooner than we think.

Read our policy paper and related work on global health security for further analysis of how the Pandemic Fund can succeed in its first year and beyond, including what we’re watching in this first call for proposals. And join our virtual event on June 20 on strategic investments in surveillance for pandemic preparedness where we’ll discuss this paper and more.

______

Background on the Pandemic Fund

After many calls for a dedicated financing mechanism to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response (PPR), the Pandemic Fund was officially established in September 2022. The Pandemic Fund aims to address critical gaps in low- and middle-income countries and provide long-term financing to strengthen PPR.

However, the Pandemic Fund is severely underfinanced; the estimated need is over $10 billion annually, but commitments as of June 2023 are at only $1.6 billion, with a fund balance of just $1.1 billion. Expressions of interest in its first round of funding totaled over $7 billion, about 24 times the current available envelope.

The Pandemic Fund’s first call for proposals is now closed, and with proposals submitted, the Pandemic Fund’s Technical Advisory Panel is tasked with reviewing eligible proposals before the Governing Board comes to final decisions in July of this year. This first round prioritizes high-impact investments in i) comprehensive disease surveillance and early warning; ii) laboratory systems; and iii) human resources and public health and community workforce capacity, with around $300 million available for these purposes.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock