Recommended

Financial service providers have a responsibility to identify their customers and understand the risks they pose before providing services. When prospective customers lack formal identification, or when their identification is difficult to authenticate, providers cannot easily verify their identities or perform customer due diligence (CDD) on them. This imposes two constraints on financial inclusion: on the supply side, expensive customer identification and due diligence procedures can render low-income customers unprofitable, constraining the size of the viable market; on the demand side, lengthy or inconvenient onboarding procedures can deter potential customers from signing up for financial services.

Efficient and effective CDD procedures can help address both constraints. On the supply side, they reduce compliance costs for providers, making it more profitable to provide services to low-income customers. On the demand side, they accelerate account opening, facilitate mobile access, and make it easier to conduct transactions. In combination, these two effects can boost financial inclusion.

In our recent paper published by Groupe Spéciale Mobile Association (GSMA), we examined two approaches to conducting customer identification, verification, and due diligence (collectively referred to as “know your customer” or KYC) that make it easier for financial service providers to take on new customers: tiered KYC and electronic KYC (e-KYC). Of the two, e-KYC is the more promising long-term approach, but also the more challenging to implement.

The promise of E-KYC

E-KYC is a process in which approved entities query a digital (and usually national) ID system to authenticate or verify their customers’ identities and, in some cases, retrieve basic information about them. E-KYC systems can improve the onboarding process by reducing or eliminating paper-based procedures and record-keeping, which reduces cost and time spent on verification, making it more profitable to provide services to low-income customers.

For e-KYC systems to be effective, however, they must be backed by a robust digital ID infrastructure with wide coverage. The World Bank defines digital ID as “a collection of electronically captured and stored identity attributes that uniquely describe a person within a given context and is used for electronic transactions. It provides remote assurance that the person is who they purport to be.”

As economic and social activity has migrated online and become increasingly mediated by mobile devices, digital ID platforms have become increasingly important to accessing services and an essential element of modern infrastructure. Of the roughly 175 countries with some form of national ID system in place, 161 are digitized and 83 collect biometric data. The figure below from Alan Gelb and Anna Diofasi Metz’s Identification Revolution highlights how quickly digital ID systems have spread over the last 20 years.

The rapid growth of digital ID programs

Source: Identification Revolution, p.17 (2018)

Enabling third party access to digital ID systems: opportunities and challenges

A digital national ID system offers a platform upon which a variety of services can be built. Today, a small but growing number of countries allow third parties to access their digital ID databases to carry out a variety of functions and services, including for elections, financial services, and healthcare. The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) identifies 22 governments that allow third parties to access their digital ID systems for the purpose of conducting KYC.

According to the World Bank’s Private Sector Economic Impacts from Identification Systems, the ability of third-party service providers to query digital ID systems may confer several benefits, including a reduction in the cost of transactions that require identification; the development of new services that depend on automatic and inexpensive identification; and a reduction in the need for private companies to collect and store customers’ personal information themselves.

Moreover, the use of a national ID system by third-party service providers may produce a positive feedback loop, insofar as it encourages people to enroll in the system and keep their personal information current and accurate. For these reasons, the ITU recommends that:

countries with a national identity system, or another similar market-wide identity system, should recognize this as a public resource. Access to this directory, and use of it, should be open to all regulated digital financial services providers at a reasonable cost.

But while enabling third party access to a digital ID system can increase its usefulness, it also raises critical safety, security, and privacy concerns. Because ID databases aggregate sensitive personal information in one place, keeping them secure is imperative.

As Gelb and Diofasi Metz emphasize, the risks presented by third party access depend largely on what information outside actors can retrieve. Systems that limit the information provided to third parties to a “yes/no” verification about whether the attributes of a customer match those stored in a database are much safer than those that provide outside actors with personal information.

For that reason, the authors recommend that digital ID systems should only allow access to the personal information required for the task at hand and answer queries with a simple “yes” or “no” without providing access to the underlying information, whenever possible. Similarly, because a centralized database presents an attractive target for hackers, government databases must have strong cybersecurity measures in place.

Learning from India

A growing number of developing countries are either implementing e-KYC or developing regulations to support its use, including Bangladesh, Kenya, Pakistan, Tanzania, and The Philippines. But India stands out for the scale of its e-KYC program, which began in 2012. The country’s experience to date illustrates the difficult balance policymakers must strike when weighing the usability of digital ID systems against data security concerns.

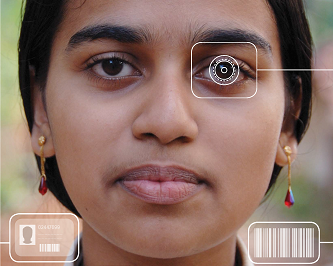

India’s unique identity or Aadhaar program has rightly captured the world’s attention for its innovativeness, rapid growth, and sheer scale. The program assigns each registrant a unique 12-digit ID number linked to minimal personal information (including name, gender, date of birth, and a digital photo) and biometric information (fingerprints and iris scans) that can be used for authentication. Since the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) issued the first Aadhaar ID in 2010, more than 1.2 billion people (nearly 90 percent of the population in India) have enrolled in the program.

The original stated purpose of Aadhaar was to reduce leakage and fraud in the government’s sprawling subsidy program by removing “ghost beneficiaries” and duplicate entries on its rolls. However, use of the ID quickly spread to other areas, including filing income tax returns, authenticating payments, and digitally signing documents.

The government has worked to expand the system’s functionality by working with tech experts to create a collection of open APIs (application programming interfaces) called India Stack, which government agencies and businesses can use to develop applications that connect to the ID database. E-KYC for financial transactions was approved by the Reserve Bank of India via a Master Direction that amended KYC rules to include Aadhaar-based verification in 2016.

Aadhaar-based e-KYC allows customers to electronically provide their demographic and personal information—including proof of identity, proof of address, date of birth, and gender—to financial providers, who can verify it in real time. One Ministry of Finance official estimated that moving from paper-based KYC to e-KYC in India reduced the average cost of verifying customers from roughly $15 to $.0.50, and Indian banks that make the shift can lessen the time spent on verifying customers from more than five days to seconds.

The introduction of e-KYC has contributed to the success of the Jan Dhan financial inclusion program, which supported the opening of over 300 million account between 2014 and 2017 (17 percent of account openings used direct e-KYC with biometric authentication, while 67 percent used an e-Aadhaar letter plus a one-time password, according to IDinsight’s most recent State of Aadhaar Report).

But the use of Aadhaar for KYC has also raised privacy concerns. Whereas the Aadhaar system was originally designed to send only “yes/no” responses to queries from outside parties, indicating whether the attributes of a customer match those stored in the UIDAI database, KYC authentication using Aadhaar provides financial institutions additional information about their customers. Privacy experts argue that this represents a fundamental change that puts consumers at risk.

The issue came to a head in September 2018, when India’s Supreme Court disallowed private entities from using Aadhaar numbers to verify the identity of their customers, arguing that the practice “enabled commercial exploitation of an individual’s biometric and demographic information.” Following the ruling, the UIDAI suspended financial service providers and mobile operators from conducting e-KYC.

Today, the situation remains in limbo. Industry actors are searching for work-arounds—like using a paper card with a QR code that encodes an individual’s personal data stored in the UIDAI database without including an Aadhaar number—while the government recently introduced a bill to parliament that would amend existing laws to provide legal backing to the voluntary use of Aadhaar for e-KYC. While it is unclear how the issue will be resolved, India’s recent track record of successful innovation by the public sector suggests that the country will find a way to overcome this hurdle, allowing the world’s largest experiment with e-KYC to go forward.

One lesson for other countries seeking to develop their own e-KYC systems, is the importance of establishing a legal framework for digital ID and its use by third parties. Although the lack of such a framework in India ahead of Aadhaar’s rollout helped to spur innovation early on, the uncertainty it has created now poses a risk for financial service providers and threatens to slow the pace of expanding financial access.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.