For months now, people have been asking, “Is the pandemic over?” Although things seemed to be improving globally, we were constantly worried that any day we would wake up to a variant that escaped our vaccines, evaded the immune systems of those who’d been previously infected, transmitted more quickly, or caused greater disease, setting us back by several months.

In late November, news of a new Omicron variant broke. It took a few weeks to work out how bad this variant would be—and indeed there is still a lot we don’t know—but it seems increasingly likely that Omicron confirms several of our fears.

High-income countries play a key role in the global response to Omicron. Their decisions can help increase global vaccination coverage, curb the spread of current variants, and prevent the emergence of new ones. Here we outline three actions high-income countries should take to help end the pandemic sooner.

1. Don’t underestimate Omicron because it seems to only cause mild disease—greater infectiousness for milder symptoms is a terrible trade

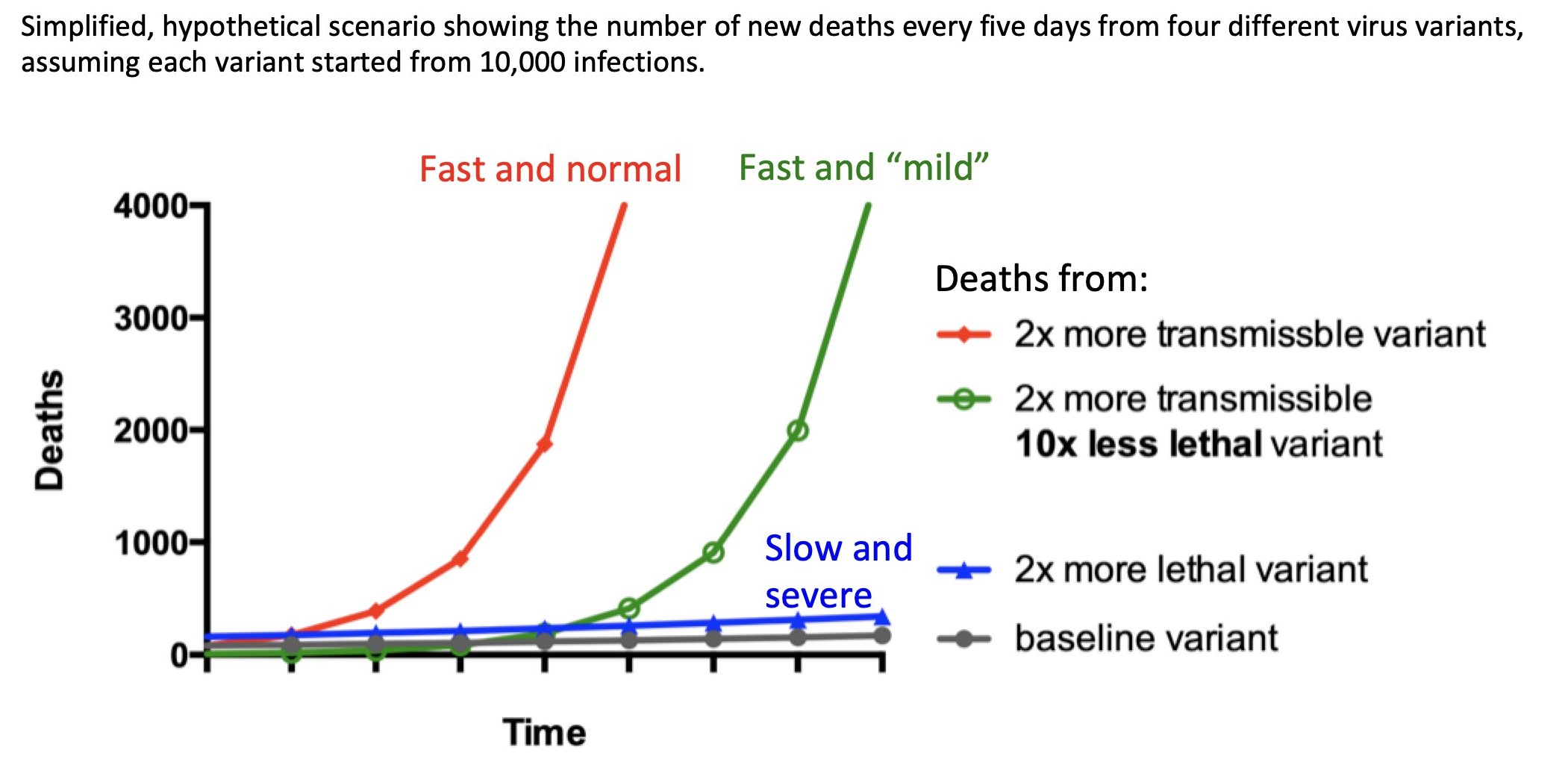

Omicron is spreading faster than any other variant has to date. With cases taking less than two days to double in the UK, the variant seems to spread around 70 times quicker than Delta. Early data suggests that Omicron might be milder than other COVID-19 variants, but it will take more time and evidence to confirm this. Regardless, higher transmission usually leds to more deaths, even when the likelihood of mortality from each case is lower. This is because even small changes in transmission compound and lead to a far greater number of cases. This is outlined below in a graph created by Dr. Malgorzata Gasperowicz, a developmental biologist from the University of Calgary. Faster transmission also means a greater strain on health systems, quicker reinfection, and more new variants.

Figure 1. A variant that transmits faster, even if much milder, could lead to many more deaths

Source: @GosiaGasperoPhD

2. Stop punishing good behaviour

South Africa did the world a huge favour by quickly identifying and flagging Omicron to the global health community. As a reward, they faced a quick imposition of travel bans. Travel bans are usually futile because new variants have probably already spread across borders before the variant is spotted. While there may occasionally be benefits to slowing the spread of variants by enacting travel bans, these will only ever slow transmission (unless countries ban travel from all countries that have COVID-19), rather than prevent it. Additionally, travel bans disrupt responses to new strains. In this case, travel bans caused vital supply chains disruptions that hindered testing to track and contain Omicron. And most importantly, travel bans punish countries that are open about their variants, discouraging sequencing and information sharing. Both of which are valuable to the whole world because as countries report new variants, the rest of the world can identify them and prepare for a wave of cases.

There are currently five World Health Organization variants of concern, and only Alpha and Omicron were quickly flagged. In both instances, the country that identified them faced isolation and travel restrictions. In contrast, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants were much slower to come to light, and the countries of origin were not met with similarly hasty restrictions.

If there are compelling epidemiological reasons to block travel to a low-or middle-income country with a new variant, there should be compensation. Countries shouldn’t face a large economic hit for doing the right thing. This will discourage good behaviour and put us all at greater risk.

3. Limit the opportunity for new variants

While the exact origin of Omicron is uncertain, Africa is a likely and logical guess. We have long known that high rates of COVID-19 transmission heighten the risk of new variants. Insufficient vaccines supplies in Africa have created a giant chink in the world’s armour. So it’s not surprising that the continent that has had the lowest vaccination rate—as shown by the New York Times vaccine tracker below—is the one where this new variant is likely to have started.

Genetically, Omicron is markedly different than other variants because it has many more mutations. Whilst the Alpha variant has an estimated nine mutations and the Delta variant has between nine and 13 mutations, Omicron is thought to have 50. Three leading theories ordered from most to least likely, suggest how a virus with so many differences could have emerged so suddenly. The virus could have survived for a long time in a single immune comprised person, giving it more time to adapt to the human immune system. The virus could have transmitted from a human to an animal, then back to a human. Or, least likely yet still possible, the variant could have spread for a long time without notice, in an area where testing or sequencing is limited.

Each of these scenarios is more likely to have arisen in Africa, where the least virus sequencing occurs, surveillance is weak, densities of humans and domestic animals are increasing, and perhaps most importantly, almost 70 percent HIV-affected people—often immunocompromised—live. Barriers to accessing HIV treatment in Africa only further weaken immune systems and exacerbate the risk of COVID-19 transmission and mutation. Increased transmission in Africa ultimately leads to a wider, faster spread of COVID-19 around the world. In short, the world’s lacklustre attempt to get COVID-19 vaccines to Africa was incredibly short sighted.

High-income countries need to do far more to expand access to vaccines in Africa. This is key now that high-income countries are implementing booster campaigns, suggesting routine booster shots, and even discussing the development of new vaccines to protect against variants. This increase in demand from wealthier nations could seriously curtail the supply for low-income countries going forward. New vaccines will also lead to a decline in vaccine output, as it takes factories months to switch to a new product. Finally, high-income countries and donors should not just provide vaccines; low-income countries increasingly need support to distribute them due to insufficient health infrastructure and state capacity.

Conclusion: Countries should focus on the long-term

While the situation is deteriorating quickly, we are still in a much better position than we were in March 2020. Vaccines still provide protection, particularly against serious illness. A lot has been learnt about the best care paths for people with severe treatment. More recently, Pfizer and Merck have introduced breakthrough drugs that are highly effective and much easier to make than vaccines. But despite the excellent work by the world’s scientific community, high-income countries are letting nationalism perpetuate the COVID-19 crisis. Hoarding supplies might alleviate some short-term pain in high-income countries, but it will make all countries worse off in the future.

In early 2020, COVID-19 took everyone by surprise. It was understandable that countries were in crisis mode and focused on the immediate term. Two years after the virus first emerged, we need to move past the idea of quick fixes and silver bullets and start working together to strengthen our global armour against this disease.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.