Recommended

How newspapers and media outlets cover a topic can affect what people believe and what they do. Research shows that news coverage affects people’s actions across many aspects of their lives, from voting to fertility. In education, violence in schools is a crucial challenge: it is common, it is insufficiently documented, it violates children’s rights, and it diminishes their educational experience. What if we could leverage the media to change norms and policies around school violence? In a new working paper, we examine how the news media cover school violence, looking at more than 200 recent news items about school violence in five countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania). We also explore the potential to leverage news coverage of school violence for change.

How the media cover school violence

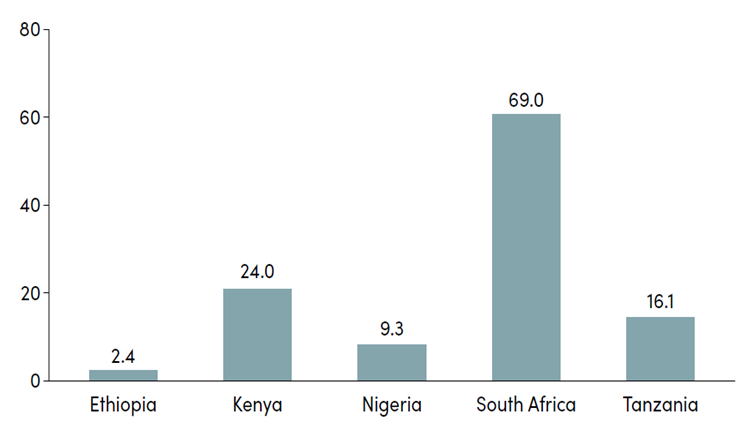

There is a lot of variation in how much the news media cover violence across countries. Even after you adjust for population, South Africa and Kenya have much larger coverage than Ethiopia or Nigeria, with Tanzania in between (Figure 1). One might be tempted to conclude that school violence is much more common in South Africa and Kenya, but we know that’s not the case. Survey data show that school-age girls are more than twice as likely to have experienced physical or sexual violence in Nigeria than they are in South Africa.

The pattern of news coverage more likely reflects how acceptable school violence is in different countries. While we don’t have cross-country on attitudes towards school violence, survey data on whether or not another form of violence (domestic violence) is acceptable suggests very low acceptance in South Africa (the country with the highest news coverage of school violence) and very high acceptance in Ethiopia (the country with the lowest coverage of school violence).

Figure 1: How many articles did we identify, per million school-age children?

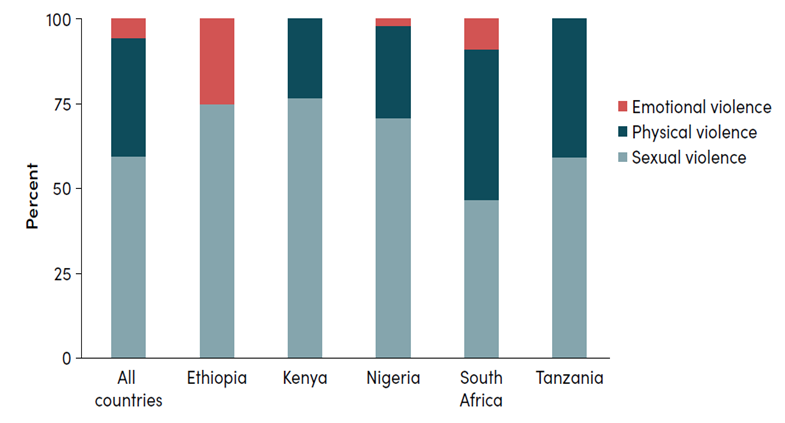

Across countries, the domestic news media are more likely to cover sexual violence in schools than they are to cover physical or emotional violence (Figure 2). This is—again—in contrast to survey data, which suggest that physical violence is much more common than sexual violence. This may again reflect how acceptable people find physical violence (including corporal punishment) relative to sexual violence. When media in high-income countries cover school violence in these five countries, the coverage is more likely to be evenly split between sexual and physical violence. This is consistent with corporal punishment being less accepted in high-income countries than in the countries in our sample (as evidenced by a higher rate of corporal punishment bans in high-income countries).

Figure 2: How much do the news media cover different types of violence?

Our finding that the news media’s coverage of school violence reflects norms around violence more than the actual underlying levels of violence points the way to leveraging the media to achieve change.

Can the media play a role in curbing school violence?

The most common recommendation in news articles about school violence is that there should be more news articles covering school violence! While one might be tempted to write this off as self-serving (like researchers suggesting more research), more consistent news coverage on this important issue could potentially play a role in changing norms. When scholars Kalolo and Kapinga studied efforts to reduce school violence in Tanzania, one challenge they highlighted is that many people—both parents and school leaders—see school violence as acceptable and even useful. One of the most successfully tested interventions to reduce school violence (the Good School Toolkit in Uganda) focused on changing those norms at the school and community level through training and discussion. News media coverage has the potential to change norms across society even more broadly. We found that most of the coverage in our sampled countries consisted of articles that highlight the issue of school violence—often mentioning several incidents at once—rather than detailed reporting on specific incidents of violence. Perhaps more reporting on specific incidents would signal that these are newsworthy.

While we focus on news media in our study, other forms of media can also play an important role. Extensive social media postings about a sexual abuse case in a Nigerian school led to coverage in the traditional news media, and they may be as likely to affect policy discussions as print media. Likewise, entertainment media may have a role to play. As far back as twenty years ago, a film set in the Central African Republic highlighted the challenge of teachers sexually abusing students. Today, we have evidence of TV shows affecting attitudes towards domestic violence and HIV-prevention behaviors in Nigeria, fertility and divorce in Brazil, and adolescent childbearing in the United States. A recent Nigerian film tackled sex-for-grades in tertiary education. Maybe it’s time for more TV and films—together with news coverage—to highlight that every child deserves a safe education.

Thanks to Amina Mendez Acosta, Maya Verber, and Gabriela Smarrelli for comments on this blog post.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: fivepointsix / Adobe Stock