Earlier this month, the first analysis of countries’ progress towards attaining the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) was published in the Lancet. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) used Global Burden of Disease Data (GBD 2016) to create an index for 37 (out of 50) health-related SDG indicators between 1990–2016, for a total of 188 countries. Based on the pace of change recorded over the past 25 years or so, the researchers then projected the indicators to 2030. The punchline: if past is prologue, the median number of SDG targets attained in 2030 will be five of the 24 defined targets currently measured. Not very inspiring.

This is an enormous and laudable effort. A wealth of information is now in the public domain, standardised and comparable between countries, and measurable against SDG attainment, past and forecast. It is clearly better than the UN’s usual glossy pamphlet, and it signals something important—under business-as-usual arrangements, not much of the SDG agenda in health will get done.

Given that scenario, GBD past and future only gets us part of the way towards our goal: using regular measurement and data to drive more and better progress, policy, and spending by governments, donors, employers, as well as healthcare and product firms and investors.

GBD helps us understand the problem we are trying to solve in macro terms—lots of preventable deaths, or inadequate prevention and management of cardiovascular disease. And GBD in the US has truly been a wake-up call—the finding that life expectancy was going down in many counties, and presenting the data in a way that attracted the attention of leaders, may eventually trigger policy action. And as self-help programs always tell us: recognizing you’ve got a problem is the first step towards a solution.

But to use GBD to effect change to business-as-usual what we need is the kind of hyperlocal data, analysis and relationships that public and private payers routinely use in developed economies to inform their own spending and make their investment cases to their countries’ Treasuries or insurers. This critical missing link can help make the causal connection between investment in health and better performance in attaining the SDGs, including Universal Healthcare Coverage (UHC).

Some key (and some surprising) findings

The researchers namecheck Turkey, Rwanda, China, Cambodia, Laos, and Equatorial Guinea as having made significant progress towards UHC (to measure this they devised a kind of meta-index combining “risk-standardised mortality rates from 32 causes from which death should not occur in the presence of high-quality health care with estimates of nine types of intervention coverage for infectious diseases and maternal and child health outcomes”). Lesotho and the Central African Republic are singled out as not making much progress at all towards UHC during that same period. Incidentally, Equatorial Guinea spends much less of its public budget on health than the African average, less than half of the Abuja target of 15% and roughly half of what Lesotho does as a proportion of its public expenditure, suggesting more money alone is not a predictor of success, but more on this later (see Fig 2 here). All in all, they find that whilst good progress is forecast for a majority of countries towards reducing under 5 and neonatal mortality and maternal mortality, other targets such as childhood obesity, TB and road traffic accidents are likely to have been met by fewer than 5 percent of countries come 2030.

A new UHC index is presented as well as violence and vaccine coverage indicators (and more work is promised by the researchers on the latter). And there is more to look forward to in GBD 2017, including health worker density and distribution, “proportion of people who feel safe walking alone around the area where they live”, a refined version of financial protection using household catastrophic spending, and coverage of treatment for substance abuse and sexual violence by non-intimate partners. Most of the above indicators, however, hinge on data availability beyond Europe and North America.

What is most exciting, perhaps, about future work, is the researchers’ commitment to attempt to attribute likelihood of SDG achievement to targeted investment for meeting the SDGs, through tackling underlying risk factors, expanding coverage to existing or new interventions we know work, or increasing development assistance in some way. It would be interesting to see how such attribution could be empirically backed through global level analyses, given the myriad of policies, technologies and fluctuating funding streams which affect healthcare systems’ outcomes and spending. Indeed, most economists have not found a good way to cope with the endogeneity problem in these sorts of analyses (a good attempt using UK programme budgeting data can be found here).

GBD is highly visible in countries too

It is unclear what the impact of GBD analyses has been at country level, but the visibility of the work in the press is impressive. Hours from the publication of the latest wave of findings, in the national and regional press, India lamented the fact it lags so far behind countries with similar characteristics such as its fellow BRICs (see here and here), whilst Singapore celebrated securing the top slot. A 2010 edition of GBD, comparing countries on their performance in public health, triggered a rare policy response by the Secretary of State in the UK, who called on payers of services to better incentivise tackling risk factors for common NCDs, in particular cardiovascular disease through national health checks, better data collection and care integration (see here). Almost five years on, with unprecedented budgetary pressures on the NHS, and most of the agencies supposed to lead on these policies renamed or abolished, there is no follow up on the impact of the measures.

What will it take to use GBD and other data to change business-as-usual SDG trajectories?

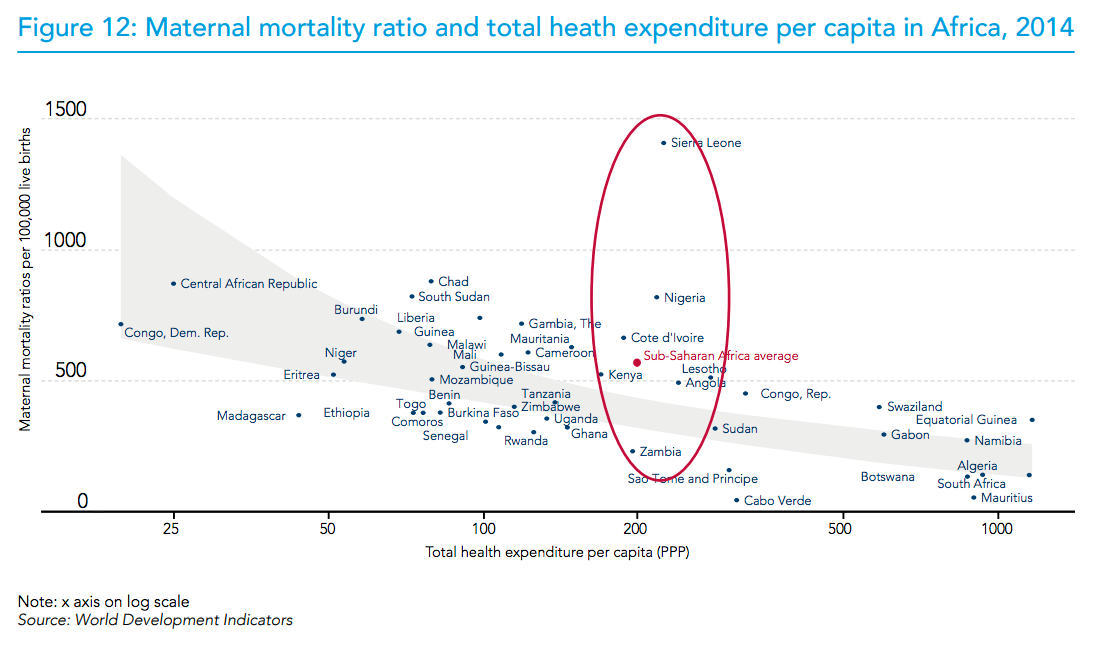

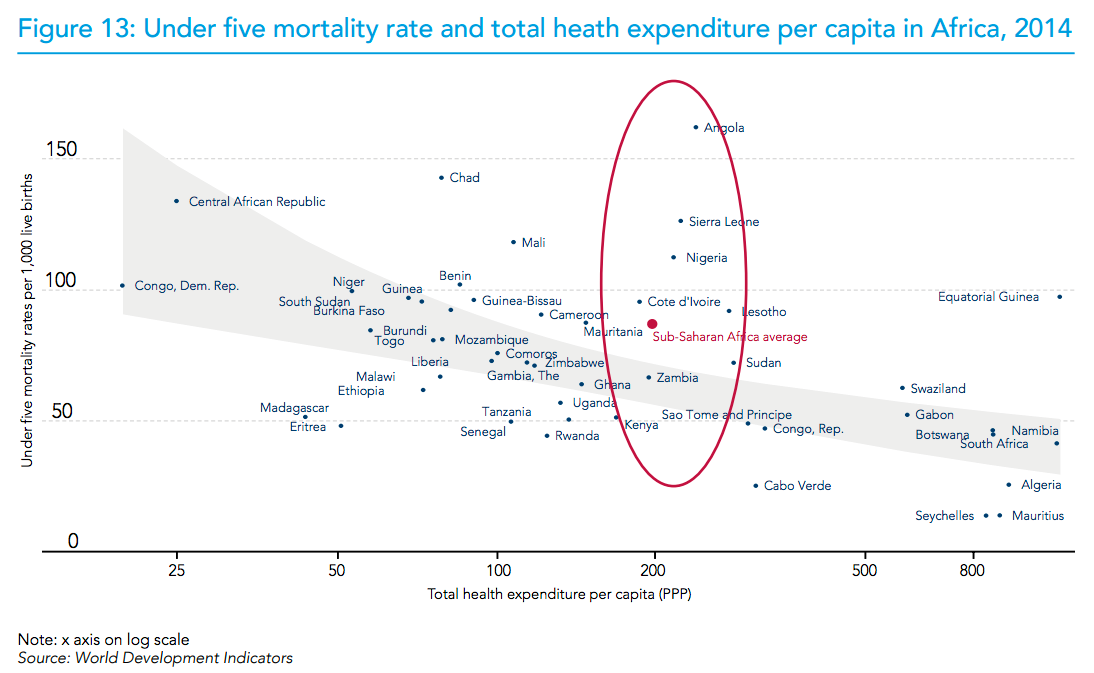

Were such analyses able to link investment scenarios (e.g. more of a certain kind of aid, or better even, specific technology adoption and scale up decisions on the part of national health payers) to progress towards SDGs, as suggested by the researchers, then a stronger case could perhaps be made to national treasuries for more and ideally better targeted spending on health. To have local credibility, such work cannot rely solely on running regressions using country panel data. After all, we know that more money for health does not lead to better health outcomes (as shown in Figures 12 and 13 of this WHO report).

GBD rankings can serve as a useful source of information for prioritising those broader diseases and conditions warranting further attention in terms of interventions in the form of more funding; better targeted, outcomes-linked funding (as the UK minister urged his commissioners based on GBD 2010 data); and technology adoption or scale up including population level and behavioural interventions for tackling underlying risk factors. But when it comes to informing specific investment cases within these broader priorities, GBD data are not enough to allow consideration of trade-offs and of opportunity costs of alternative investment choices addressing the same problem. And this is precisely what is needed both in order meaningfully to attribute improvements in performance to investments in technologies or disease areas and to allow domestic payers and national treasuries to make confident allocation decisions including directing more domestic funds towards their own healthcare spending.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.