Recommended

REPORTS

Beth March died of a disease that would have taken 10 days to treat with penicillin; she was just 23. A whole section of Anna Karenina is driven by the prolonged illness and death of the 30-something Nikolai Levin, who could have been cured with a course of antibiotics and very little handholding. Entire essays are devoted to the role of rain-induced illness (most likely pneumococcal pneumonia) as a plot device in Jane Austen.

Antibiotics take the drama out of what would otherwise be life-threatening illnesses. In 1930, 283 out of every 100,000 people in the United States would die of an infectious disease; after Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928 (and it was first used in humans in 1941), these rates plummeted: by 1980, the figure was just 36 out of every 100,000.

But like Superman, antibiotics have a weakness. Their kryptonite is that the more we use them, the faster bacteria evolve to resist their powers. This is already a big problem: right now 8.9 million people die every year from bacterial infections, and about five million of these deaths are from resistant infections. That means, globally, we need to manage our antibiotic use to reduce the speed with which bacteria develop resistance, and to speed up the rate at which we discover and develop new antibiotics that bacteria have as yet limited resistance to.

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is an economic problem

Getting this right is not just a clinical problem for healthcare professionals and researchers to solve. It’s an economic problem. As an editorial in Nature noted after the recent discovery of a potential new class of antibiotics, the discovery will not amount to much if the economics is not also addressed. Yet it is striking that even this editorial identifies only one or two very specific economic problems in the supply of new antibiotics.

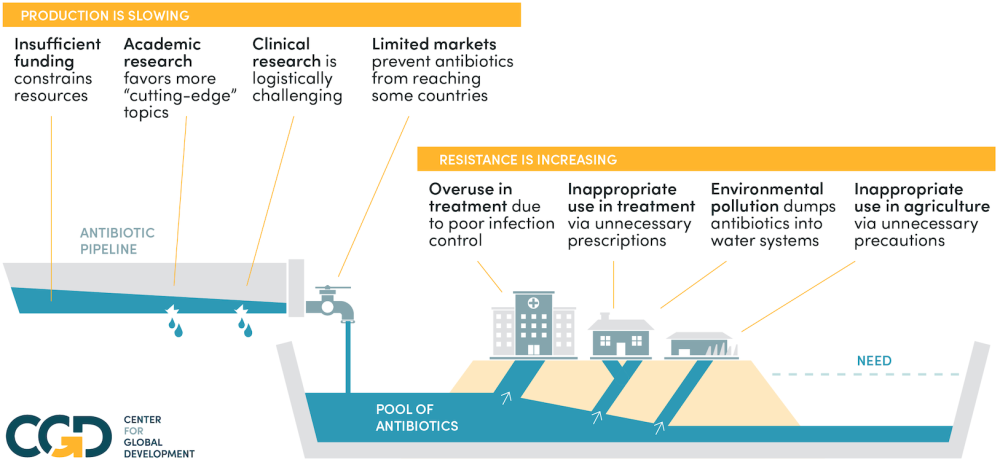

In a new paper, we document that these problems are only the tip of a very large iceberg indeed. Almost every aspect of the process of discovering, producing, buying, and consuming antibiotics is riddled with market and government failures that are well-known to economists from other contexts, but not enough work has been done to comprehensively examine how these failures affect ABR. We document 10 separate economic failures affecting aspects of antibiotic development, production, and use that contribute to an unacceptably rapid development of resistance. These are mainly market failures (cases where the market leads to inefficient outcomes) but also include government failures (cases where government regulation and intervention makes the problem worse, not better). None of them will be unfamiliar to economists on their own; what makes the case of antibiotic resistance so difficult is that so many apply at different stages, which means that the traditional solutions for any one of the problems sometimes don’t apply.

To solve resistance, it’s not enough to solve just some of these market failures. If we fix the market failures that reduce the number of new antibiotics that are discovered, but not the market failures that lead to their overuse, new antibiotics will just buy us a little time before resistance emerges again. If we solve the failures affecting overuse of antibiotics in some countries, but not their underuse in others, then resistant bacteria will simply emerge in some places before spreading across the world. If we fix all of the market failures in the process of innovating new antibiotics, but don’t address the regulatory failures that prevent us from getting these new drugs to the market, all that innovation will be for nought.

The market and government failures causing ABR

That’s why we’ve tried to produce a truly comprehensive treatment of the market and government failures that lead to ABR: because only by considering all of them together can we identify a set of solutions that will, collectively, solve the problem.

It’s too big and complex to solve bit by bit: we need an overview before solutions will start to make sense. We give a very brief rundown of each problem below: click on the problem to see a brief description of it.

This is the overarching problem of antibiotic resistance: our stock of effective antibiotics is a finite resource for which there is no effective mechanism to moderate demand. The result is a tragedy of the commons: everyone uses antibiotics a little too much, and we will be left with none that work.

The economics of antibiotic supply failures

Innovations in antibiotic development have public good characteristics. The idea underlying a new public good is non-rivalrous (lots of people can use this idea to produce the new antibiotic) and only imperfectly excludable (patents must be used to prevent people from copying new drugs). The normal solution to this problem, extending patent protections, is inappropriate because of market failures on the demand side that lead to ABR.

The social and private value of new antibiotics are poorly aligned. The private value is limited by the fact that new antibiotics are mainly important for reserve use, and that resistant infections are a particular problem in poorer countries with lower ability and willingness to pay; but their social value as insurance for situations where first- and, if available, second-line antibiotics fail is very high.

Even in cases where these concerns are overcome and a potentially viable antibiotic is identified, the regulatory hurdles these antibiotics are required to clear to reach market render the cost of achieving regulatory clearance inefficiently high. This is a regulatory failure in which the attempt to solve one problem (the marketing of ineffective or harmful drugs) has introduced a new problem (the failure of effective drugs to clear regulatory approvals).

As already alluded to, much of the value of new antibiotics is not in their use but their insurance value. As the Nature editorial put it, “[T]he commercial market is dismal by design. A new antibiotic often costs more than US$1 billion to develop, but the reluctance to use it widely means that it is likely to earn less than $100 million a year once on the market.”

The supply of generic antibiotics can be unreliable. They are not profitable enough for producers to invest substantially in supply chain resilience; but this means there are occasional supply failures and stockouts. The social cost of such failures is substantially larger than the private cost, as the failure to treat infections promptly can lead to the spread of infections that require antibiotic use, or the use of last resort antibiotics which should be kept back for insurance purposes.

The economics of antibiotic demand failures

Infection control can prevent the spread of bacteria and so reduce the number of infected individuals needing antibiotics (thus reducing antibiotic overuse). However, the costs of good infection control at the individual level are private: the cost of washing hands regularly, using face masks where appropriate, and so on. The benefits at least partly accrue to others, by preventing their infection. As such, individual action to reduce the spread of disease is underprovided. Furthermore, much infection control relies on the provision of public goods, such as water treatment and basic health and sanitation infrastructure. Such goods require state provision, which is not always forthcoming, especially in poorer countries.

Optimising the use of antibiotics involves more antibiotic use by many people in poor countries, with low willingness and ability to pay for antibiotics, since in these places better use of antibiotics can prevent infections spreading and thus requiring even more antibiotic use in the future. It also involves reducing overuse in developed and many middle-income countries, where willingness to pay for antibiotics is higher than their true private value, due to informational failures: people often believe that antibiotics will help them recover when they may not; and in the absence of quick, convenient and accurate diagnostics, doctors may prescribe antibiotics even when they are unsure of their value in treating a specific illness. This is a mismatch problem: prices cannot perform the function of matching supply and demand in a way that maximises social value. Solving it requires resolving inequity of access and fixing the information problems that result in over- or under-use.

Pharmaceutical production often results in the discharge of active pharmaceutical ingredients into rivers without proper deactivation. This kind of environmental pollution, which can result in higher levels of resistance by exposing bacteria to antibiotics in the environment, is a classic negative externality in production, with well-understood solutions. The problem is that regulation and enforcement in some countries is weak.

There are negative externalities in production of agricultural products, too: many farms use antibiotics for growth promotion in livestock, which again contributes increased resistance. But this social cost doesn’t enter into the cost-benefit calculations of farmers, so they tend to use more antibiotics than is socially desirable. Again, policy tools to address this exist, but have yet to be implemented and rigorously enforced.

We don’t list these issues out because we’re defeatist. We do it precisely because we have policy tools that can solve each of them, and in our paper, we list many of them. But solving some and not others is not enough: the best way to keep these Superman-like drugs working is to make sure that we get all of the economics right. We can do this. But it will take a good understanding of the problems, which our paper aims to provide.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe