-

Forget schools! Just let the kids learn from MTV! In Nigeria, watching a show called MTV Shuga—which “presents young Africans from various socioeconomic strata balancing bright futures with the negative consequences of high-risk behaviors”—affected viewers in a range of ways: they knew more about HIV; they reduced concurrent sexual partnerships; and female viewers were less likely to catch a sexually transmitted disease. This is from a newly released study by Banerjee, La Ferrara, and Orozco. (A control group watched another TV show filmed in Nigeria—Gidi Up—with a similar setting but no educational content.) You may wish to watch the first episode of Shuga before you go on your next date. (Or, if you’re feeling reckless, I guess you could just watch Gidi Up.) Earlier, the same authors found that watching the Shuga also led male viewers to hold more negative views about violence against women.

-

You can’t just enroll in school. You have to go to school. A major concern with teens is that they’ll drop out of school. But consistently missing school—even without dropping out—can also have big impacts. In a US study by Liu, Lee, and Gershenson, just 10 absences from math class over the course of the school year significantly decreased test scores, grades, the likelihood of graduating on time, and the chance of enrolling in college right away. Absenteeism towards the end of the school year was particularly detrimental.

-

Childcare: good for kids and good for moms? Publicly provided childcare centers in Nicaragua significantly increased children’s social development and increased their mothers’ work participation as well, according to new work by Hojman and Boo. The impacts were largest for the poorest families and—in terms of the impact on children’s development—better quality centers likely led to better outcomes.

-

Education: it’s not just for children anymore! There are 750 million adults around the world who are not functionally literate. Bendini and Levin review both the evidence on what works to bring adults to literacy and the programs that try to accomplish that. It turns out that few resources are invested in adult literacy programs, and only 1 in 20 programs that they reviewed managed to bring adults from illiteracy to reading comprehension. Effective adult literacy programs have some characteristics in common: they bring adults across each building block of literacy in sequence, and that takes time—300–400 hours to get an adult to second or third grade reading. They are built to cater to adults’ busy lives and foster social interaction with peers to maintain motivation. Adults’ brains are less malleable than children’s, but they compensate with better attention spans and larger spoken vocabularies (which helps with understanding texts). Technology can help, as experiments both in the United States and Niger show.

-

Recruiting and preparing better teachers is harder than it looks. Brazil passed a law stipulating that all teachers had to have completed their post-secondary education as of 2007. (In many countries, it’s common for primary school teachers to have studied a special course in secondary school.) New analysis of the impact of that law on student learning suggests that it had some impact on student math scores but not on reading. (Surprisingly, there is no impact from more teachers having actually studied math.) Barbosa and Costa suggest that the limited impacts may stem from teachers having studied with low-quality, distance learning programs and easy teacher training programs: “Tertiary teacher training courses are among the easiest ones to access in Brazil. Low competition to enroll in these courses reflects the low attractiveness to higher performance graduates of basic education.”

-

Cash for long-term education gains. Thirteen years after a conditional cash transfer program in Honduras, Millán and co-authors find that beneficiaries who got the transfers while at school age were more than 50 percent more likely to complete secondary school and make it to university. (The gains were smaller for indigenous kids.) The transfers also boosted international migration. This adds an optimistic ingredient to our growing knowledge about the long-term impacts of cash transfers.

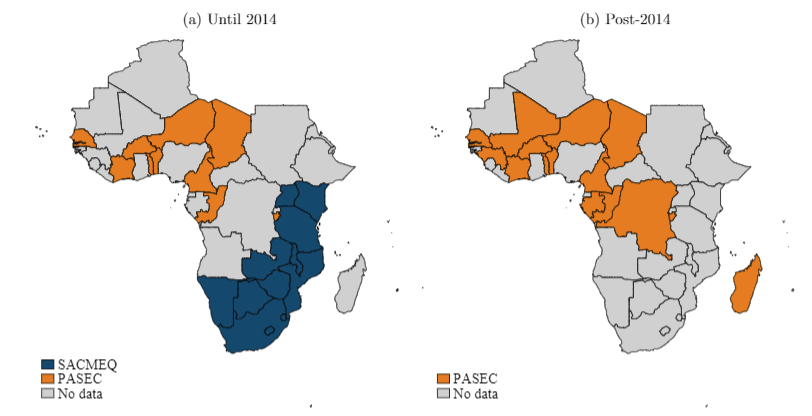

In case you missed it, we’ve been busy researching and writing about education here at CGD. Last week, Crawfurd proposes that lowering the voting age could increase domestic spending for education. Bruns and Akmal make the case that African countries should invest in more data on learning that is comparable with other countries, building on a paper with Birdsall. The week before, Crawfurd outlined how algorithms have made allocating students to schools fairer in the United States and shows how they could apply to secondary schools across many African countries. (He references one of my favorite modern economics books, economics Nobel prizewinner Alvin Roth’s Who Gets What—and Why: The New Economics of Matchmaking and Market Design.)

Figure of the week: Regionally comparable testing coverage in Latin America and in Africa, from Bruns, Akmal, and Birdsall

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.