Violence in and around schools is a serious problem. Sexual violence, physical violence, and emotional violence—from school staff as well as from fellow students—are all damaging to children and youth. As secondary education expands around the globe, violence against adolescent girls in school merits special attention. But growing attention to school-based violence doesn’t mean that girls are safe outside of school. In fact, the relationship between violence and education is complicated. On the one hand, going to school exposes adolescent girls to violence from teachers, other school staff, and peers—both at school and on the way to and from school. On the other hand, staying out of school often means either marrying earlier, which can increase the risk of intimate partner violence, or entering the workforce, with exposure to violence from bosses and coworkers. (While this post focuses on girls, boys are also not immune to violence.)

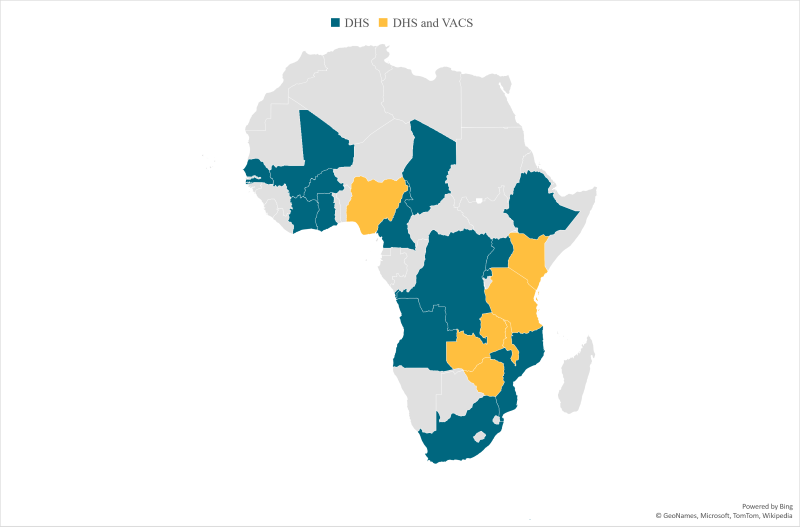

In a new working paper, we examine the rates of sexual and physical violence against adolescent girls (ages 15-19), both for those enrolled in school and for those who are not. We use both a household survey that has been applied in many countries but has less detail on violence (the Demographic and Health Surveys, or DHS) and a survey focused on violence against children and adolescents but with less coverage (the Violence against Children and Youth Surveys, or VACS). Using a sample that represents more than 80 percent of girls aged 15-19 across sub-Saharan Africa, we reach two conclusions: first, the rates of violence against adolescent girls, in or out of school, are disturbingly high, and second, girls are generally no less safe at school than they are out of school. If policymakers are serious about reducing violence against adolescent girls, they should be aiming to reach girls both in and out of school.

Rates of violence are alarmingly high for all girls, in or out of school

Across the countries in our sample, nearly 29 percent of girls report having experienced either physical or sexual violence at some point. (Remember that since people often underreport violence in surveys, these are likely underestimates.) If we break that down into different types of violence, 26 percent of girls report having experienced physical violence. This ranges from 13 percent in Ethiopia to 41 percent in Uganda (Figure 2).

The two surveys we use ask about different types of sexual violence. The VACS use a broad definition of sexual violence and document that about one in eight girls (17 percent) have experienced sexual violence in the past 12 months. About 10 percent of that violence is reported to take place at school. Most of that violence is either unwanted sexual touching or attempted unwanted sex. The DHS survey uses a narrower definition, asking only whether girls have been “forced” to engage in sexual acts: using a longer timeframe (whether they’ve ever experienced this type of sexual violence), more than one in every 13 girls (8 percent) reports that this is the case. That ranges from less than half a percent in Burkina Faso to more than 16 percent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Figure 2. Rates of reported physical and sexual violence across 20 African countries

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Demographic and Health Surveys and Violence Against Children and Youth Surveys.

Rates of violence are not higher for in-school girls, suggesting the need for interventions both in school and out of schools

The biggest challenge with comparing rates of violence for girls in and out of school is that girls who go to school are different from girls who don’t go to school. In addition to comparing girls of similar ages, we adjust our comparisons based on three pieces of information that can both inform resources for education and norms around education: parents’ education, socioeconomic status, and whether the girl lives in a rural or urban area (Figure 3).

On average, girls currently enrolled in school are slightly less likely to report having experienced either physical or sexual violence previously. In two countries in our sample (Mozambique and Nigeria), girls in school are significantly more likely to report having experienced physical violence. In no country in our sample are girls significantly more likely to report having experienced sexual violence. This general pattern—that girls’ exposure to violence is similar or slightly lower if enrolled in school—holds if we restrict the analysis to violence in the last year, if we look at slightly older girls (who are sometimes in school), or if we restrict to girls who have never lived with a partner. These are not causal estimates, since we cannot correct for all differences between in-school and out-of-school girls, but they do provide suggestive evidence that urgent efforts are needed both in and out of school.

Figure 3. Relative risk of violence in and out of school

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Demographic and Health Surveys.

Note: The numbers reported here are the adjusted rates of violence reported by girls who attended school the past year minus rates of violence reported by girls who did not attend school the past year. We control for the country, age, type of residence (urban/rural), parents’ education, and wealth index from household assets to report the adjusted rates.

Takeaways

Schooling confers a wide range of benefits on girls, so continuing to expand girls’ education should be a top policy priority. But countries and their partners need to know more, do more, and test more.

First, too few countries gather systematic data on violence in or out of schools. We need further innovation on the best ways to elicit accurate data on violence against girls without putting those girls at any additional risk. Without regular measurement, countries can’t know if they are making progress on the problem.

Second, while most countries have some sort of national plan in place to prevent violence, in our paper we find no correlation between the existence of those plans and the level of violence in the country. These general plans aren’t enough. There are tested interventions to reduce violence, and more countries and education systems need to adapt and implement these interventions.

Third, countries need to test more. To echo what Devries and Naker wrote earlier this year, we need to test more interventions to address violence and we need to invest in adapting effective models into programs that can be effectively implemented at scale.

Children and youth should be safe at school. That safety should continue when they leave school grounds. Countries and partners need to invest in both.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock