Recommended

More than ever, low and lower middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs) are in a race against time. Their ambition to deliver prosperous economies for their citizens appears continuously thwarted by different shocks. There is a growing sense of urgency among these economies as it becomes clear that they will have to run faster to avoid falling behind. The International Development Association (IDA), established in 1960 to help the world’s poorest countries, is a critical financing tool, providing these countries with grants and highly concessional loans to support their socioeconomic development. However, as donors’ development ambitions have increased, their contributions to IDA have fallen in absolute and relative terms.

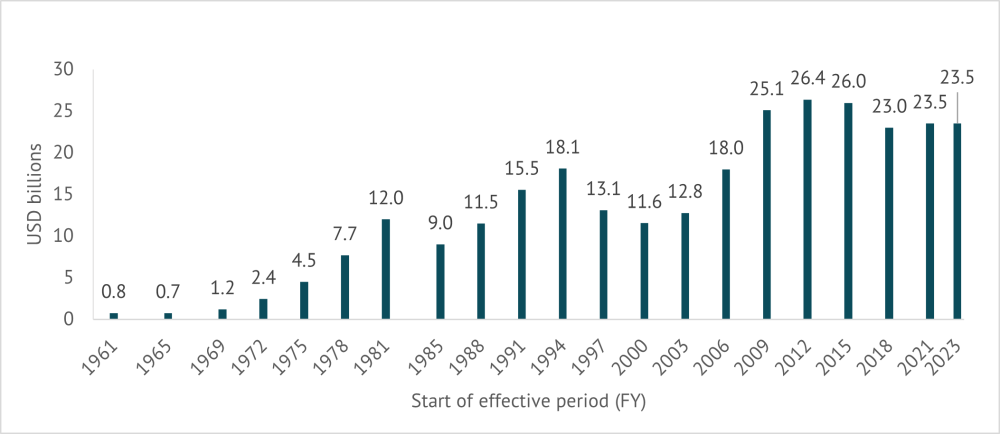

Figure 1. IDA replenishment donor contributions

Source: Scott Morris, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, IDA replenishment reports

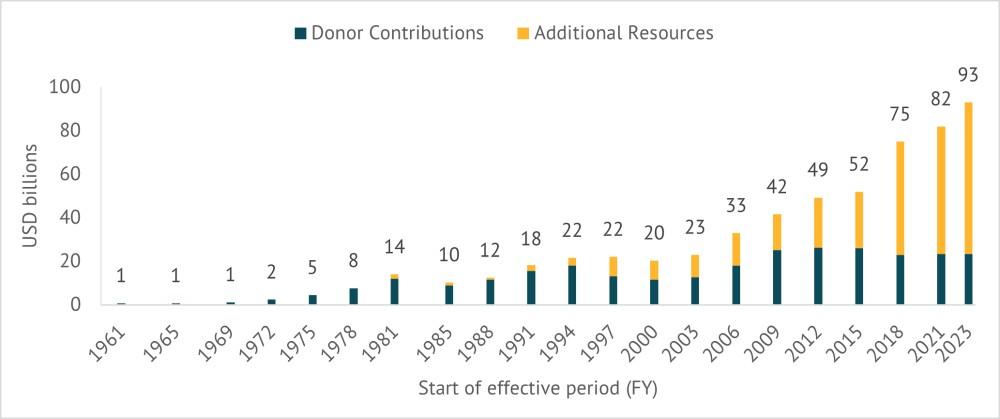

IDA has increasingly leveraged its now-substantial balance sheet to grow its replenishment figures, drawing on loan reflows and using its AAA credit rating to borrow against its $180.3 billion loan portfolio. As a result, total replenishment volume has continued to grow even as donor contributions stagnate.

Figure 2. IDA replenishments, by source

Source: same as above

Growing needs

While IDA has stretched its balance sheet, LICs and LMICs development needs have grown even faster. The developing world has glided from one crisis to another, making the need for additional resources ever more urgent. As highlighted in the Songwe, Stern, and Bhattacharyya report, emerging market countries will need $2.4 trillion in investment between now and 2030 to meet the challenge of limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius. The report identifies three big categories of needs: energy transformation, climate adaptation, and conservation of natural capital. For all three priorities, time is of the essence; delayed investment in adaptation and resilience now will lead to painful costs down the line, as natural disasters grow more frequent and more costly.

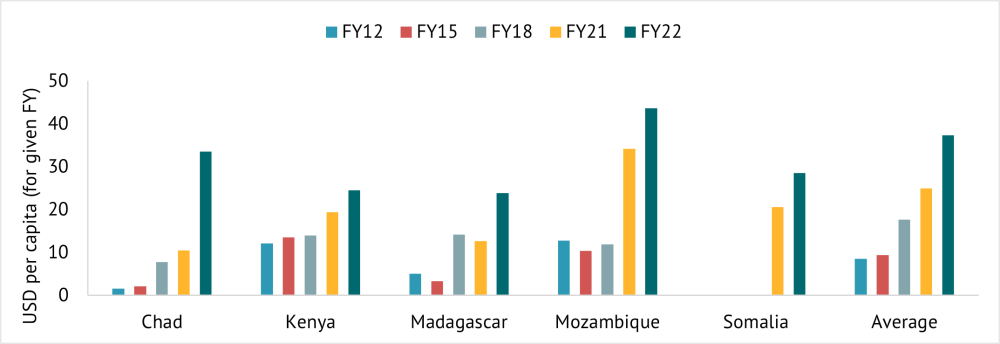

Countries exposed to climate vulnerability such as those in Figure 3 have seen their IDA allocations grow in per capita terms, but not significantly beyond the average IDA allocation increase (far right); they need substantially more to manage the exponential increase in climate-related destruction that they face.

Figure 3. IDA allocations per capita to climate vulnerable countries, in context.

Source: World Bank: IDA Financing, World Bank Open Data

Box 1. 2022 Bridgetown Agenda

The Bridgetown Agenda is a proposal to transform the existing system of development finance to be better suited to the needs of climate vulnerable nations. Spearheaded by the Prime Minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, it is the product of a context in which developing countries are facing three interconnected crises: a cost-of-living crisis, a debt crisis, and a climate crisis.

To lay the path for a new financial system that drives finance towards climate action and the Sustainable Development Goals while stopping the emerging debt crisis, the Agenda calls for:

- Providing emergency liquidity through special drawing rights (SDR) rechanneling, the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), and debt suspension clauses (DSCs) in debt instruments

- Expanding multilateral lending to governments by US$1 trillion

- Activating private capital for climate action through new multilateral mechanisms

For LMICs especially, concessional finance from IDA is crucial to achieving this scale of investment, not least because the rising cost of capital precludes many from tapping into private capital markets.

As emphasized in the Songwe et al. report, countries should not have to incur excessive additional debt to address climate challenges. This notion is comprehensively discussed in the Bridgetown Initiative (see box) which calls for debt suspension clauses (DSCs) in country debt which will trigger an immediate debt service suspension in the aftermath of a severe climate event. The inclusion of such a provision, combined with the catastrophe loans introduced by the World Bank and the Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) of the IMF are all positive efforts to help countries address the impact of natural disasters. However, as many countries that have gone through cyclones will attest, a debt service suspension may not cover the full costs of these disasters. Countries will need additional resources to address adaptation issues and build resilience.

The war in Ukraine has laid bare the low agriculture productivity of Africa and the need for a fully integrated continental plan to shore up Africa’s food systems. This medium- to long-term strategy will require over $200 billion dollars as investments in ports, logistics, storage, and seed and soil technology are upgraded to not only meet Africa’s needs but also build more robust sustainable food systems for the global market.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposed how little the world had invested in human capital development, from health to education to social protection. The gaps were more acute in low-income countries. Today, countries are struggling to make up for lost education years, rebuild health systems to secure care for all, and improve the targeting of social safety net programs.

All these new and old challenges cannot be addressed with the same quantum of resources. A much bigger IDA is needed. The international community must agree on the need for a comprehensive look at reform of the global financial architecture and put IDA, and the LICs and LMICs it serves, at the center of the reform agenda.

A call for a more ambitious IDA

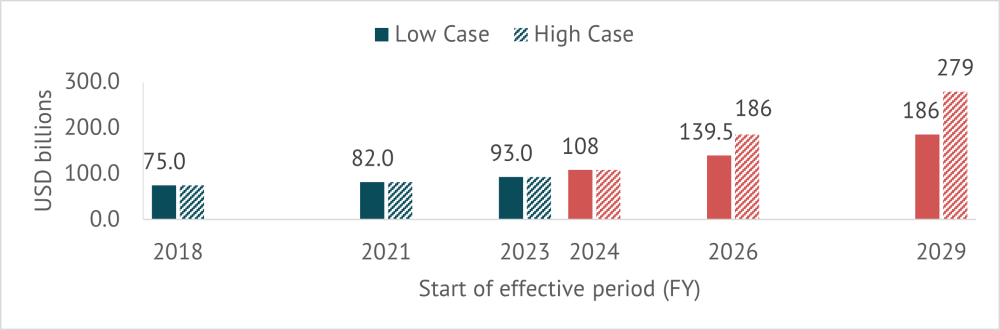

An advanced replenishment to support the demands of countries is the first step to increasing IDA. The initial IDA20 replenishment of $93 billion was frontloaded to deal with the COVID-19 crisis, but the ongoing war in Ukraine, tightening of US interest rates, deteriorating climate outlook, and continued disruptions in supply chains all point to another difficult year ahead. For these reasons, we argue that IDA20 should be adjusted to reflect the new normal in demand by countries. This means maintaining predictability in borrowing from IDA at $38 billion. This will call for the adjustment of IDA from $93 billion to $108 billion (IDA20+).

Beginning from this new normal, donors should commit to tripling IDA between now and 2030, in line with the tripling of multilateral development bank resources called for in the Songwe et al. report. This will provide countries and the private sector with the kind of predictability needed to achieve sustainable development while keeping climate change within 1.5 degrees.

Table 1. IDA replenishment scenarios

|

IDA envelope (USD billions) |

IDA20 (2023-2025) |

IDA20+ |

IDA21 |

IDA22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Low case |

93 |

108 |

139.5 |

186 |

|

High case |

93 |

108 |

186 |

279 |

Figure 4. Potential IDA replenishment scenarios

Low Case – Doubling IDA. In this scenario, IDA21 would be $139.5 billion or $46.5 billion per year over the three-year cycle. The IDA22 envelope would be $186 billion or $62 billion per year over the three-year cycle.

High Case – Tripling IDA: A billions to trillions opportunity. This scenario gives countries a fighting chance at meeting the SDGs, responding to the climate challenge, and leveraging the private sector on a scale of 1:4 to get to the trillions. IDA21 would be $186 billion, or $62 billion per year over the three-year cycle. IDA22 would be an ambitious $279 billion, or $93 billion per year over the three-year cycle.

The scale of the challenge ahead is daunting. However, giving countries a sufficient head start will allow the global community to credibly expect positive results by 2030, and rebuild trust in our collective goals.

Note: This blog post was updated after publication to remove one graph that mis-interpreted data from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). The upward trend in natural disaster frequency that this data shows is at least partly due to better reporting, making it problematic to attribute the historical increase primarily to climate change. It was also updated to correct one footnote around the size of IDA's balance sheet.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock