Recommended

In the last 40 years, antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed HIV/AIDS from an incurable death sentence to a chronic disease, allowing people with HIV to live long, healthy lives. But in 2018, 40 percent of people living with HIV did not have access to treatment. As countries face reductions in donor aid and increased pressure to finance health programs with domestic resources, donors and governments must make tough decisions about how to allocate healthcare budgets across multiple programs.

Priorities must be set. For example, the 2018 Kenyan universal health coverage budget was $352 million USD, of which the HIV response alone would absorb at least 67 percent.[1],[2] As donors phase out assistance, country governments will continue to face challenging tradeoffs. Alongside health outcomes, the economic impact of health investments is crucial to priority-setting and health benefits design, especially as countries move away from siloed disease-specific programs and out-of-pocket spending toward universal health coverage.

Previous research on the household-level economic benefits of HIV treatment focused on people living with HIV and their household members.

While evidence for the macroeconomic benefits of AIDS treatment is mixed, much accumulated evidence attests to the substantial microeconomic benefits of ART to HIV-positive patients and their households. ART improves health and life expectancy, increasing the work productivity and wages of those living with HIV.[3],[4],[5],[6] HIV treatment also benefits household members; caretakers are freed to pursue employment outside of the home and child health and education outcomes improve.

Benefits of treatment that accrue primarily to people living with HIV and their households compete with other health services for financing—these services have few spillover effects, such as the treatment or prevention of injuries or of non-communicable diseases. But treatment and prevention of communicable diseases like tuberculosis, HIV and vaccine preventable diseases deserve a higher government spending priority because they generate beneficial spillover effects (or “positive externalities”) for people outside the household. The greater the evidence for the beneficial spillover effects of ART, the stronger the argument is for governments and donors to prioritize ART spending. One of the strongest arguments for the spillover benefits of ART outside the household was made by Granich et al. (2009) in a classic modeling paper which argued that, because ART reduces HIV transmission and prevents the transmission of other infectious diseases like TB, it is actually cost-saving. Since that paper was published, other modeling papers, including one co-authored by one of us, have used similar assumptions to show that HIV treatment, even if not cost-saving, could have a high rate of economic return. Unfortunately, newly published rigorous empirical results from the “Test and Treat Trials” cast doubt on these modeled results.

As we recognize World AIDS Day on December 1, and as PEPFAR budgets remain flat and face significant reductions, we highlight empirical results demonstrating extra-household spillover effects of ART, which support HIV activists in advocating for the continued prioritization of funding for HIV treatment.

But new research shows that HIV treatment leads to economic benefits for entire communities.

In a recent CGD seminar, Associate Professor Zoë McLaren of the UMBC School of Public Policy presented unpublished results of a new paper, co-authored with Jacob Bor, Frank Tanser, and Till Bärnighausen, which breaks fresh ground by assessing the economic spillover effects of HIV treatment on communities in rural South Africa from 2004 to 2011. The researchers estimate that, among those living within two kilometers of the nearest ART clinic, employment increased by 7.6 percentage points for all HIV-negative people, and by a statistically significant 6.3 percentage points for HIV-negative people who had no HIV-positive household members.[7] In a population in which only 29 percent of adults are employed, increasing employment by 6.3 percentage points constitutes a 22 percent increase in employment among people who are not themselves directly affected by HIV.

That’s huge. To our knowledge, no other health treatment has been shown to have such positive economic spillover effects outside the household of the treated person.

HIV treatment also seems to reduce unpaid care work for women.

The study’s findings have implications for unpaid care work, the focus of CGD’s Annual Birdsall House Conference later this month. Around the world, women bear a disproportionate share of unpaid care responsibilities, including caring for sick household members. The gender imbalance of unpaid work robs women and girls of economic and educational opportunities and results in less efficient workforces and economic growth.

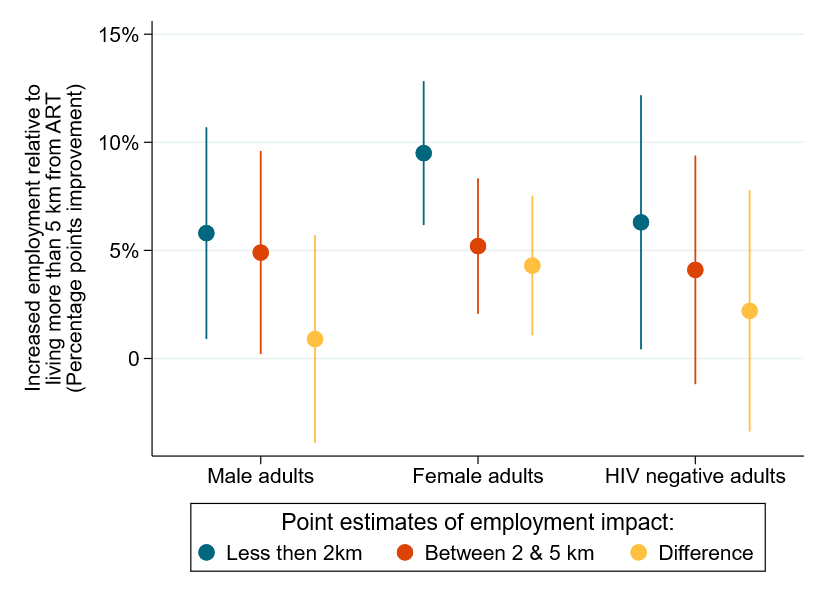

Several details of McLaren’s presentation summarized in Figure 1 below suggest that the spillover benefits of government- and donor-financed ART accrue even more to HIV-negative women than to HIV-negative men. When the authors distinguish employment impacts by gender (but not by disease status), the increase in employment for those living within two kilometers of the treatment facility is almost twice as large for women as for men (compare the first two blue error bars). However, among adults living between two and five kilometers from the treatment facility, the benefits are equally large for men and women (compare the first two orange error bars). Thus, as illustrated by the first two yellow error bars, distance from treatment reduces the employment benefits of ART for women by more than four times as much as distance reduces those benefits for men.

Figure 1. The impact on employment of nearby HIV treatment compared to employment among those living more than 5 km from treatment

Source: Authors’ computations based on McLaren, Zoë, Jacob Bor, Frank Tanser, and Till Bärnighausen, “Economic Stimulus from Public Health Programs: Externalities from Mass AIDS Treatment Provision in South Africa,” as presented by Associate Professor Zoe McLaren at a seminar at CGD on October 9, 2019. Error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals, constructed by -coefplot-. Bars for the differences are estimated by blog authors, assuming the standard errors of the coefficient differences equal the means of the coefficients’ individual standard errors.

Their finding that proximity to treatment improves female employment more than male employment can be partly explained by previous research co-authored by one of us on the same South African data that shows that, among women, living one additional kilometer away from the nearest clinic was associated with a 6.6 percent reduction in the rate of linkage to care and a 5.4 percent reduction in rate of retention on ART. In contrast, among men in the same communities, distance had no statistically significant impact whatsoever on either linkage or retention. Thus, McLaren and coauthors’ findings that women experience a larger increase in employment than men and that this increase declines more quickly among women could be due entirely to the direct benefits of ART accruing differentially to women close to the clinic.

Turning to the spillover benefits on the HIV-negative population, the first two error bars in the right-most cluster in Figure 1 display the study’s estimated employment increase among HIV-negative individuals without any HIV-positive household members. McLaren’s presentation highlighted the estimated benefits to this group, which includes both men and women.[8] Since no one in these households benefits directly from ART, the statistically significant 6.3 percentage point increase in employment can be interpreted as a pure spillover benefit. Possible explanations include increased economic activity in the vicinity of the ART clinic, resulting partly from increased productivity of HIV-positive individuals and partly from the spending of both providers and patients around the clinic.

However, in this group of HIV-negative men and women, distance substantially decreases the employment benefit of ART, just as it did for all women. Since none of these individuals, nor any of their household members, are required to travel for treatment, why would distance reduce the spillover benefits of treatment? The answer may lie in the disproportionate share of caregiving shouldered by women.

Assume that women are more likely than men to fill in for neighboring women who are too sick to perform household care duties. Since proximity to clinics encourages HIV-positive women to seek treatment, proximity would also reduce the need for HIV-negative female neighbors to help with household care duties. This phenomenon could explain why the economic benefits of treatment among HIV-negative individuals in households free of HIV are sensitive to distance: HIV-negative women in HIV-negative households are indirectly affected by neighboring women’s treatment uptake more than HIV-negative men in the same communities.

The large and statistically significant reduction in both the linkage to care and the employment benefit for women that is associated with distance to the clinic adds a gender dimension to discussions of whether governments should incur diseconomies of scale in ART provision in order to offer treatment in smaller, less-utilized facilities located closer to the homes of rural HIV-positive people. These findings suggest that locating ART clinics closer to women will not only favor women’s access to treatment, but also disproportionately relieve women of the burden of unpaid care work.

Linking women to HIV treatment makes all the difference.

While questions remain regarding the specific causal pathways for the spillover benefits of HIV, the implications of McLaren and colleagues' study for health program investments are profound. First, the spillover benefits of treatment on people in HIV-negative households are remarkable and suggest that economic planners should include the possibility of broader employment benefits when valuing the impact of health care investments. Second, the reasons that HIV treatment spillover benefits disproportionally accrue to women are likely to include the fact that women bear most of the burden of caring for chronically ill HIV patients. To unleash the economic potential of female contribution to the labor force, countries must invest in ways that minimize the need for unpaid care work. Along with spending on water supply, transportation, childcare, and other investments to reduce and redistribute unpaid care work, countries can reduce the care burden and thereby increase female employment by preventing and treating care-intensive health conditions, especially HIV/AIDS.

[1] Chaitkin, Michael, Meghan O’Connell, and Joseph Githinji. 2017. “Sustaining Effective Coverage for HIV, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in the Context of Transition in Kenya.” Results for Development.

[2] Ministry of Health, Kenya. 2018. “National and County Health Budget Analysis FY 2016/2017.”

[3] Thirumurthy, Harsha, Joshua Graff Zivin, and Markus Goldstein. 2008. “The Economic Impact of AIDS Treatment: Labor Supply in Western Kenya.” Journal of Human Resources, 43(3): 511-552.

[4] Bor, Jacob, Frank Tanser, Marie-Louise Newell, and Till Bärnighausen. 2012. “In A Study Of A Population Cohort In South Africa, HIV Patients On Antiretrovirals Had Nearly Full Recovery Of Employment.” Health Affairs, 31(7):1459-1469.

[5] French, Declan, Jonathan Brink, and Till Bärnighausen. 2019. “Early HIV treatment and labour outcomes: A case study of mining workers in South Africa.” Health Economics, 28(2): 204-218.

[6] Habyarimana, James, Bekezela Mbakile, and Cristian Pop-Eleches. 2010. “The Impact of HIV/AIDS and ARV Treatment on Worker Absenteeism.” Journal of Human Resources, 45(4): 809-839.

[7] McLaren, Zoë, Jacob Bor, Frank Tanser, and Till Bärnighausen. “Economic Stimulus from Public Health Programs: Externalities from Mass AIDS Treatment Provision in South Africa.” Forthcoming.

[8] McLaren and her co-authors are not sure they have the statistical power to disaggregate by gender their sample of HIV-negative individuals who have no HIV-positive household members.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.