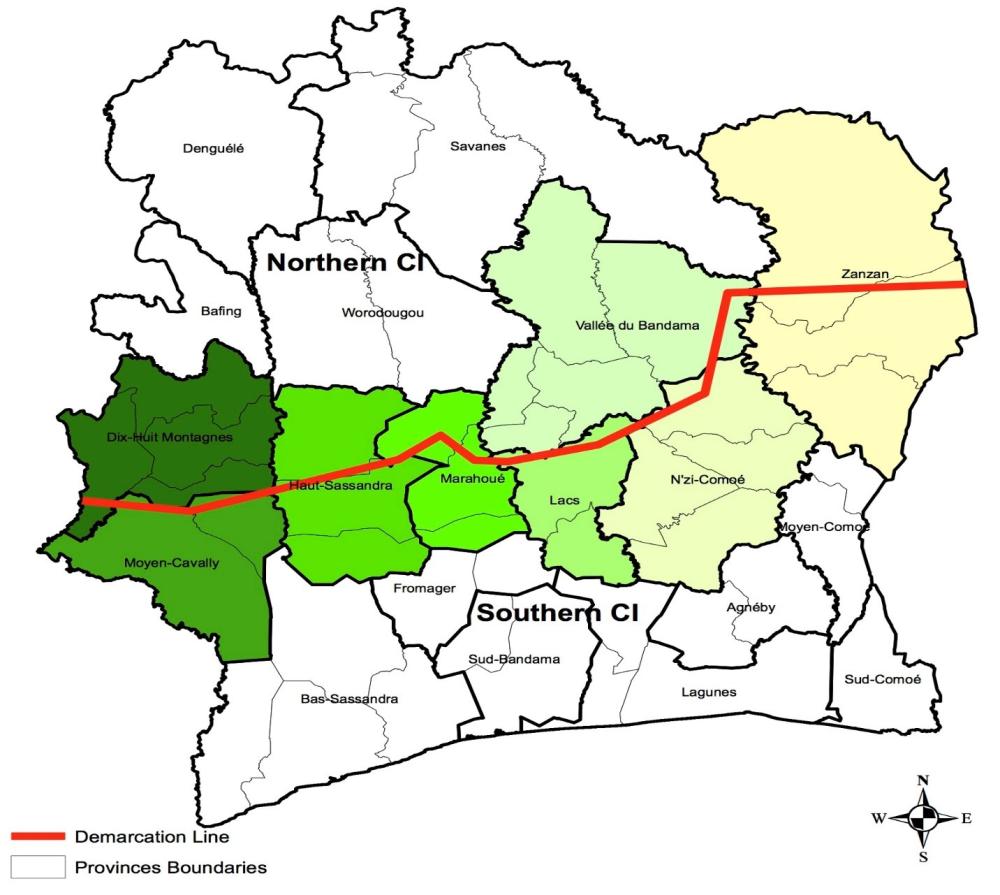

In the 2000s, Côte d’Ivoire plunged into a decade of political violence. In September 2002 the Forces Nouvelles de Côte d’Ivoire (FNCI), a coalition of three rebel movements, occupied the northern half of the national territory (Figure 1). Unlike other rebel movements in Liberia and Sierra Leone, which allegedly used “scorched-earth” and “denial-of-resource” tactics, the FNCI opted for an autonomous self-governance system. They preserved some of the public infrastructure, including power plants and water systems. Small businesses like bakeries, convenience stores, restaurants, and even a few factories continued to operate. Local and international NGOs were allowed to provide a minimum service in education and health.

The rebels also introduced an unprecedented agricultural trade reform: they cut export taxes on cocoa beans produced in their territory by nearly 50 percent.

That may seem to be a trivial detail of what amounted to civil war, but it does set the conditions to empirically test the causal effects of export taxes on the welfare of farmers, which is what I do in a paper forthcoming in Economic Development and Cultural Change.

Figure 1: Rebel-held North and Government-Controlled South

The demarcation line separating the rebel-held north is a buffer zone placed under the surveillance of international forces. Regional and provincial boundaries are described by thick and thin black lines, respectively. The colored regions, with different levels of degradation, represent the districts split between the two states.

Why Export Taxes?

Many countries with dysfunctional or ineffective tax collection sidestep that institutional inefficiency by turning to more targeted collection schemes, such as agricultural export taxes. Policymakers may favor export taxation instead of widespread taxation in weaker institutional settings for three major reasons: (1) taxing exports can generate high and reliable incomes for governments, (2) export taxes are easy to collect at borders and ports, and (3) export taxes are not forbidden under the WTO rules. Nonetheless, economists have warned that high and persistent export taxes may depress farmers’ earnings, deter production, and eventually decrease public receipts. While this argument has an intuitive appeal, empirical evidence of a causal link between agricultural export taxation and farmers’ living standards is scarce. I fill this gap by exploiting an exogenous trade policy shock (the FNCI’s 50 percent tax reduction) to examine how cocoa export taxation affects rural farmers’ lives.

Measuring Effects of the Trade Reform

Côte d’Ivoire’s government maintained export taxes at the prepartition rates of $0.44 per kilogram, while exporters faced on average $0.20 per kilogram in the rebel-held areas, according to Global Witness. Did this large reduction in export taxation actually translate into tangible benefits for cocoa farmers in the rebel-held north? Or did the deleterious political environment generated by the conflict obscure expected gains from the liberalization policy?

To answer these questions, I gathered prepartition (2002) and postpartition (2008) information on cocoa and non-cocoa farmers across the government-controlled south and the rebel-held north, and I built a triple-difference estimator. Specifically, I compare changes in consumption between cocoa and non-cocoa farmers in the rebel-held districts with changes in consumption between cocoa and non-cocoa farmers in the government-controlled districts, before and after the division. To refine the identification, I also use a subsample of communities that resided in districts split by the demarcation line separating the two de facto states. Because district creation often obeys certain socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic coherences, treatment and control groups from these split districts have the advantage of being more comparable.

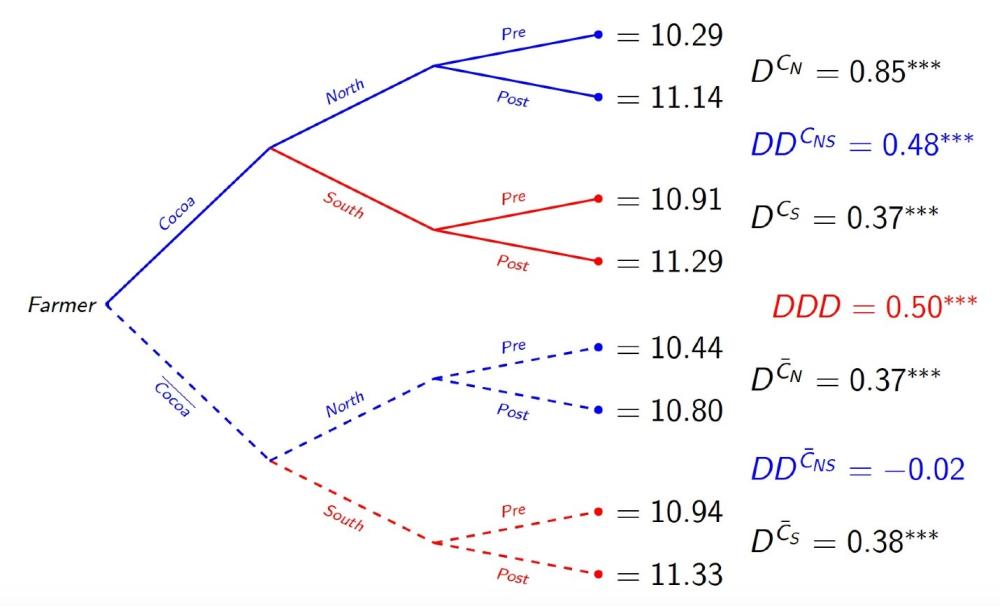

Figure 2: Cocoa Export Taxation and Consumption – A Triple Difference Estimation

The top half of the figure shows log per capita consumption expenditure for cocoa farmers, and the bottom half shows log per capita consumption expenditure for non-cocoa farmers. Blue lines indicate measures in the rebel-held north, and red lines indicate measures in the government-controlled territory. Difference estimation measures from pre- and postpartition periods are given to the right, with double-difference between the north and south shown, as well as a triple-difference estimation in the middle showing a 50 percent increase in per capita consumption expenditure among cocoa farmers in the rebel-held north.

Welfare Gains from Lower Export Taxation

My baseline specification suggests that cocoa farmers in jurisdictions with low export taxes experienced approximately a 50 percent increase in consumption expenditure, relative to their counterparts in high-export-tax districts (Figure 2). The affected farm households allocated relatively more resources to basic needs such as food, clothing, and health care. However, relative investments in children’s education decreased as a result of the cocoa export tax reduction. This is not surprising because favorable conditions in the cocoa sector and anticipation by farmers of a long-lasting beneficial policy often pull children away from schools and into the cocoa fields. Looking at potential mechanisms, I also show that farm-gate prices were 12 percent higher in the north, with exporters facing lower taxes willing to pay a higher price to the farmers. More reassuring, the apparent modest increase in prices generated revenue that was twice as much as the relative change in consumption expenditure.

Overall, my paper has three key policy implications:

- Agricultural export taxation has a sizable effect on farmers’ earnings.

- While countries with large market power, like Côte d’Ivoire in the cocoa market, can often justify the use of export taxation, non-optimal levels of export taxes could shift farmers’ incentives toward alternative crops or activities and be detrimental to the country’s market shares.

- Efforts to design optimal export taxation in countries with market power should be emphasized.

These findings suggest that relatively open policies, in addition to their well-known long-run benefits to development, could also enhance welfare in the short-run.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.