India represents about one fifth of global disease burden, and much of it is preventable. Yet India’s government spends only 1 percent of GDP on health, of which 80 percent is subnational, raised and spent by states themselves. Recent reports suggest that expenditure by the central Ministry of Health and Family Welfare will be reduced by 20% for the current financial year to achieve fiscal deficit targets. But in spite of these cuts, an accessible, affordable, and effective health system is still a priority for Prime Minister Modi’s government.

The government’s strategy is to run more central money directly to states in the spirit of ‘cooperative federalism’ – a strategy some called Modi’s “biggest bang political reform.” However, state-level public service provision in India has chronically underperformed and is plagued by poor quality and corruption (see here and here).

While life expectancy has increased dramatically over the past decade, it has been a challenge to directly link improvements in health outcomes with public spending on health or health services. For example, the National Rural Health Mission’s (NHRM) budget tripled between 2005-06 and 2011-12, but failed to lower India’s infant mortality, maternal mortality, and total fertility rates to targeted levels. Similarly, while NRHM enabled state governments to convert more than 14,500 primary health facilities to 24/7 facilities (an increase of 500%), the influx of money failed to increase doctor attendance rates in these facilities.

The advent of Rashtriya Swastha Bima Yojana (National Health Insurance Scheme, RSBY) and other state-level health insurance schemes did lead to increases in financial protection for the poor but there has been little good news elsewhere to report (and some incredibly bad news here: Are Institutional Births Institutionalizing Death?).

This begs the question: how can spending the same money through current arrangements really make a difference?

What we know about current programs

Understanding the impact and limitations of current programs is a first step to finding the answer. Both NRHM and RSBY require better evaluation, particularly of their impact on health. In the meantime, a couple of issues stand out.

First, NRHM was a noble mission designed by well-meaning Delhi bureaucrats to strengthen state health systems. However, in practice, the scheme adopted a one-size-fits-all approach that placed little regard on the socio-economic diversity across states and forced states to buy into conditions that may have limited innovation or created unnecessary structures – a health center had to look a certain way, an “accredited social health activist” or ASHA had to be part of the plan. India is simply too big and too decentralized to require single solutions for health care provision.

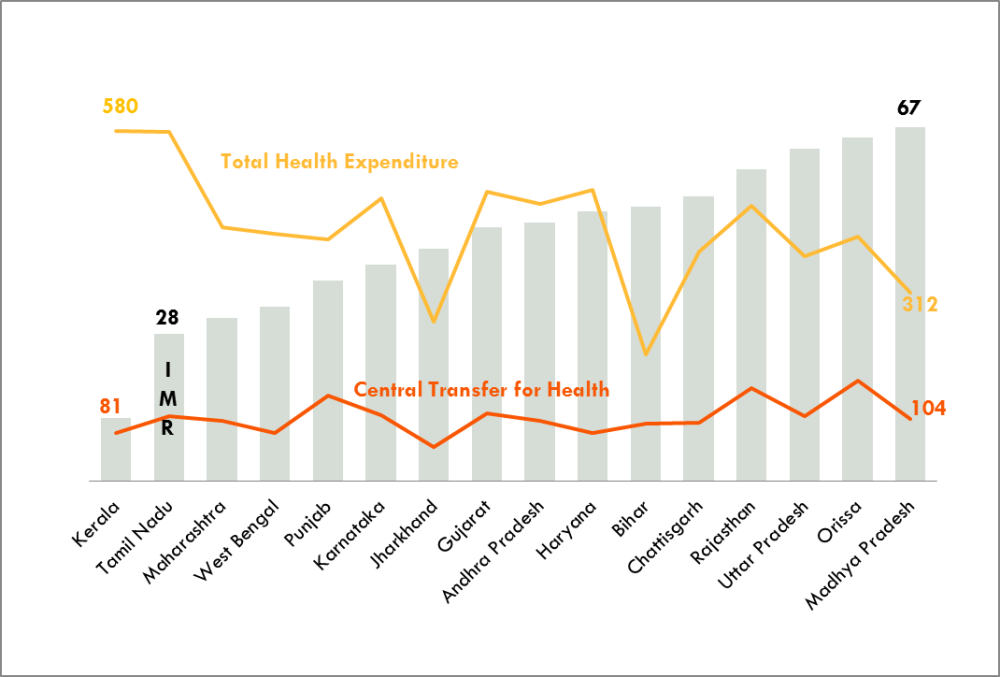

Second, a main problem with centrally sponsored schemes in general is that federal monies have done little to respond to need; the figure below illustrates that center-to-state transfers are divided more or less equally across states on a per capita basis in 2009-2010, with no regard for differences in need nor the amount of funding that states mobilize themselves for health. While states like Kerala may have enough of their own funds to reduce IMR, states like Uttar Pradesh require greater levels of central assistance to tackle this problem.

Finally, the current approach does little to relate funding to gains in health and health care. There is a small performance-related transfer currently in the NRHM but forthcoming work suggests that the rewards formula as currently designed does not in fact reward performance. In the absence of transfers that reward performance, the state and center are stuck in a principal-agent trap and efforts must be made to realign these incentives.

Infant Mortality Rate and Per Capita Health Expenditures across Indian States in 2009-2010

Notes: Per capita expenditure in Rupees (current prices). Total Health Expenditure and Central Transfer for Health are on one scale and IMR is on another.

A better way forward

Before implementing a new reform, government will need to examine current programs, the fiscal architecture underpinning centrally-sponsored schemes and identify the health outcomes it would like to see improved. A two-pronged approach of equalization grants and performance/accountability incentives may help India strengthen its system of fiscal transfers as well as its health system.

Equalization grants don’t mean the same amount of money for every state as is current practice, but instead should level the playing field so that the poorest states are able to provide a similar standard of health care as the wealthiest state. This means that a portion of federal monies should compensate for differentials in levels of underlying health and fiscal need. Some thought should also be given on how central monies do or do not incentivize a state’s own fiscal effort on health.

As for performance incentives, India may consider models where the central and state governments collaboratively design a performance-based resource allocation to link a district’s funding to its health needs. Each district might automatically receive 70 percent of its base allocation; to claim the remaining 30 percent, a district could improve performance according to defined indicators including quality and coverage. This approach, tried out in Argentina’s Plan Nacer and Pakistan’s Punjab province for example, gives a clearer incentive to improve delivery as well as outcomes.

Better and timelier data, and rigorous monitoring and evaluation, are also needed, whatever transfer scheme is adopted. One key near-term data issue relates to costing; proposed health insurance benefits plans are not costed but instead extrapolated from spending on existing insurance schemes, not recognizing state-level differences in need and cost structures, and inefficiencies in existing provision. Further, relating costed benefits plans to sizing and risk adjustment of center-to-state transfers is also pending. In too many countries, a benefits plan has little to do with the amount of per capita public transfer to subnationals actually available, which may argue for starting from the budget constraint to set priorities.

India is not alone

While we’re doing a deep dive on India with our partners at the Accountability Initiative, the country is not alone in facing these kinds of challenges, where health and fiscal policy collide at the local government level. In Kenya, as local governments assumed full responsibility for health care provision, at least three separate center-to-county flows for health were recently created, some conditional, some unconditional, and none allocated or structured to enhance health equity, accountability and impact (see work from the International Budget Partnership here). In Nigeria, a new National Health Act creates a new earmark on federal-to-Local Government Area transfers for the delivery of primary health care and legislates budget shares to be used for specific activities, but fails to set up accountability arrangements using data, funding or other tools. Stay tuned for more work here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.