Recommended

Politicians, donors, celebrities, and researchers alike have all made the case for investments in girls’ education. But despite the evidence and the advocacy, women still have less education than men in two-thirds of the world’s countries.

That doesn't mean there hasn't been progress. In our newly revised working paper—“Gender Gaps in Education: The Long View,” we use data across 50 years and 126 countries to see how far the world has come on women’s education, as well as where it’s headed. (We use the Barro-Lee education data and focus on everyone over the age of 15 in countries outside the original OECD nations.)

We identify four facts.

Fact 1: Women are more educated today than at any point in history.

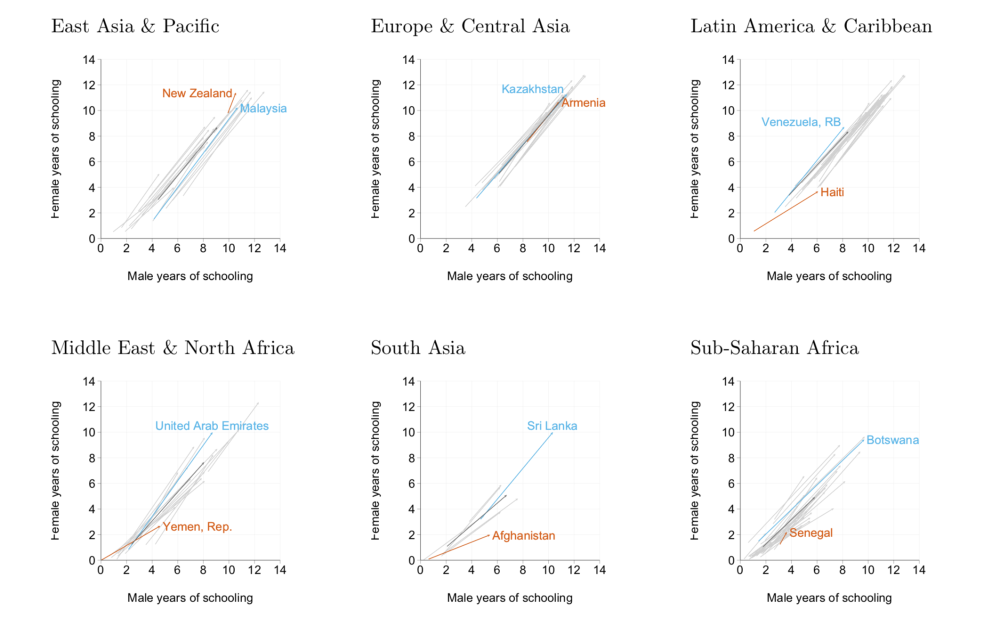

Let’s start with some good news. In every region of the world, women have more education today than they did in 1960. Even in the countries with the least gains for women in each region—Haiti in the Caribbean, Afghanistan in South Asia—women are more educated today than ever before.

Fact 2: Women are still not as educated as men.

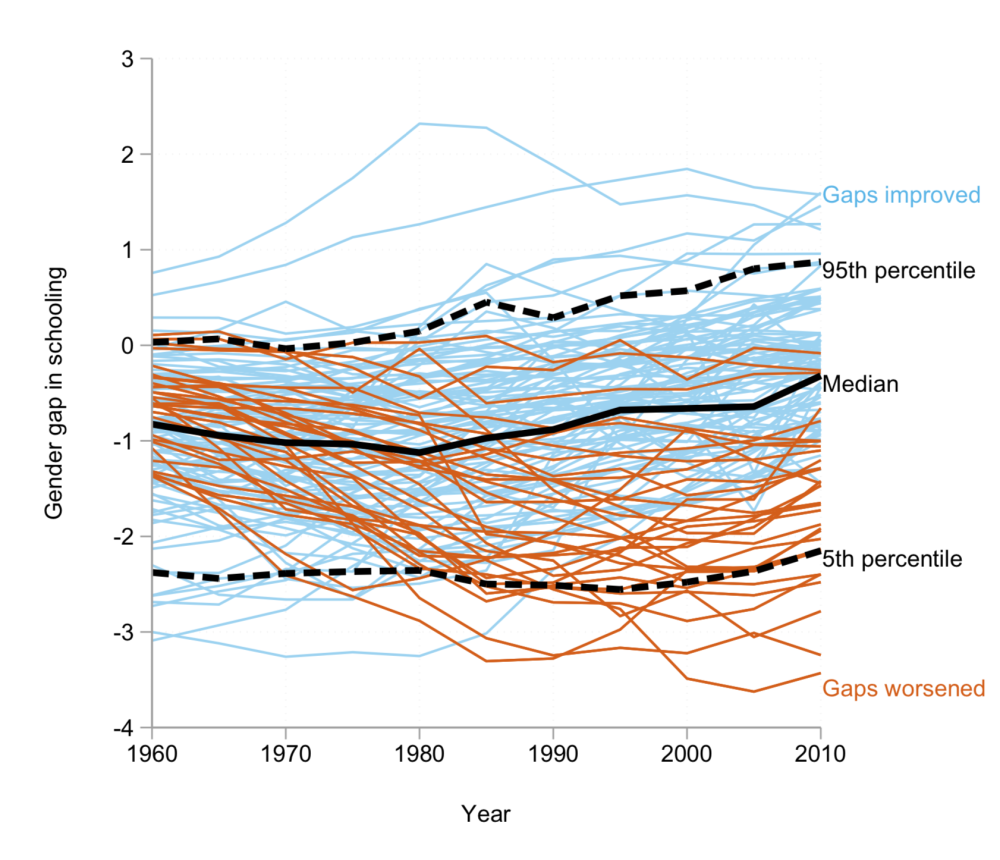

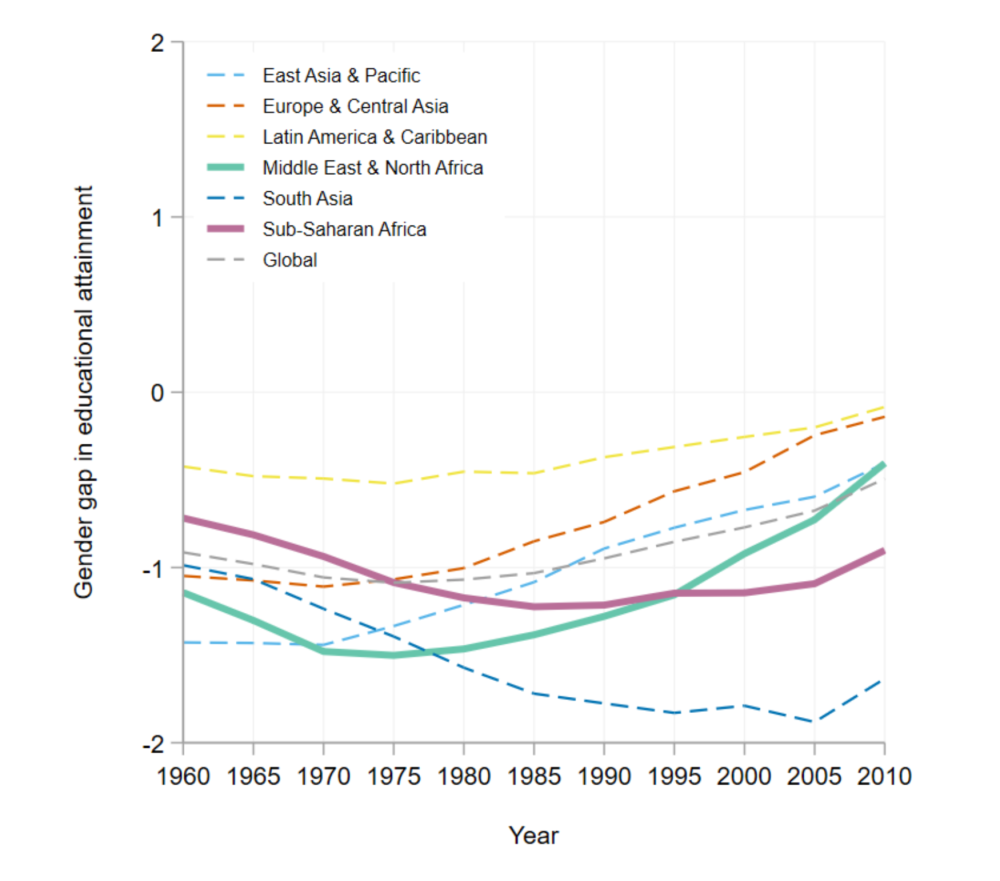

Now some not-so-good news. On average, across the world, women are still less educated than men. The median gender gap has narrowed from 0.8 fewer years for women to 0.3 fewer years, but it’s still not zero. In every region, the gap is still negative, and women are still more likely to have no schooling than men.

There are a number of countries (36!) in our sample where the trend has reversed. For example, women now have more education than men in 13 out of 25 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and in 5 out of 22 countries in Europe and Central Asia. But worldwide, women’s education still lags.

Fact 3: Gender gaps often get worse before they get better.

In three-quarters of the countries we look at, the gender gap actually widened after 1960, before beginning to narrow again in most cases. In Sub-Saharan Africa, women had 0.72 fewer years of education in 1960, but they had 1.22 fewer years in 1985. In 2010, the gap is 0.90, still not having reached the level from 50 years earlier. In the Middle East and North Africa region, the gap also widened before narrowing.

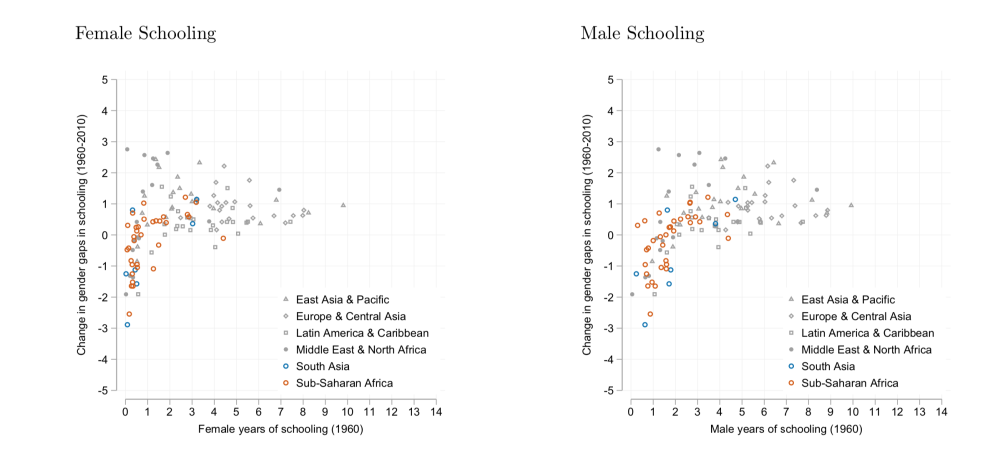

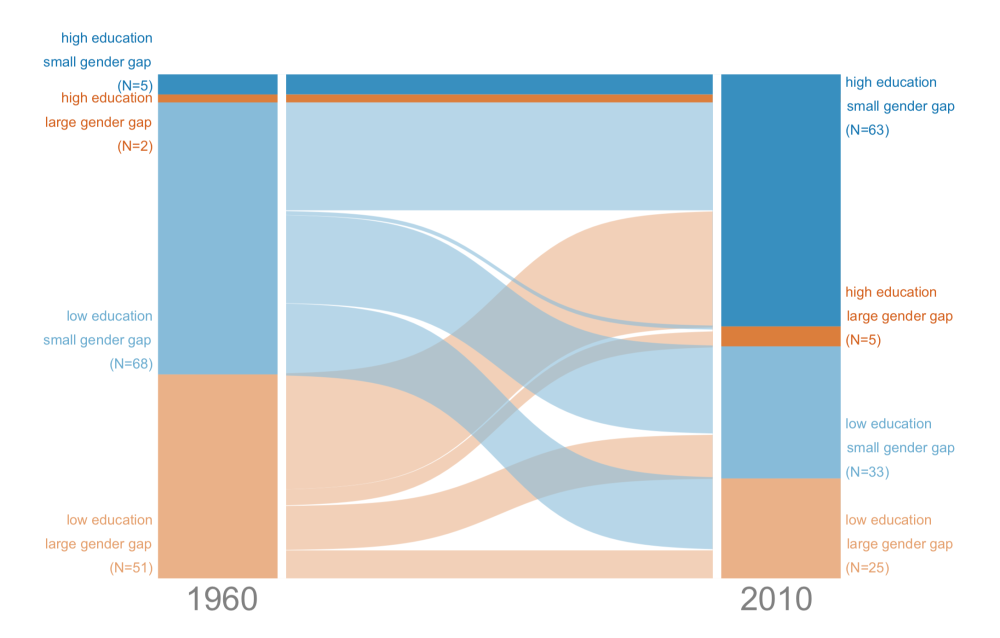

This phenomenon mostly shows up in countries where—in 1960—both men and women had little education, as you can see in the figures below. It’s hard to have much of a gender gap in education when the overall level of education for both boys and girls is low. In many of these countries, households and society invested in boys’ education first as educational opportunities became available, widening the gender gap, and only later invested in girls’ education.

Fact 4: Gender gaps rarely persist in educated countries.

In 1960, men in just seven countries in our sample had at least eight years of education. In five of those countries, the gender gap was small, at less than a year. By 2010, 68 countries had high levels of education for men—and 63 of the 68 had small gender gaps. That’s more than 90 percent. By contrast, nearly half of countries where men had less education faced gender gaps of greater than a year. Gender gaps usually narrow (or even disappear or reverse) once countries invest in education.

But it isn’t just an education problem. Many of the countries that retain large gender gaps in 2010 face a host of other development challenges: lower life expectancy, lower income levels, and more likelihood of being a fragile or conflict-affected country. Gender gaps in education often reflect far deeper societal problems.

What does the future hold?

In the analysis above, we focus on everyone above the age of 15. But what if we focus on the younger women and men? Among women age 20-24, the gender gap now favors women in more than half the countries in our sample. South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa are key exceptions, with even younger women still achieving less education than men.

The fact that gender gaps rarely persist in countries where men have high levels of education is borne out even more strongly in the younger generation, with less than five percent of high-education countries retaining gender gaps larger than a year.

For more detail on which countries seem to be on track to eliminate gaps soon and which are moving in the wrong direction, check out the paper.

Will gender equality in education alone yield economic equality? Probably not.

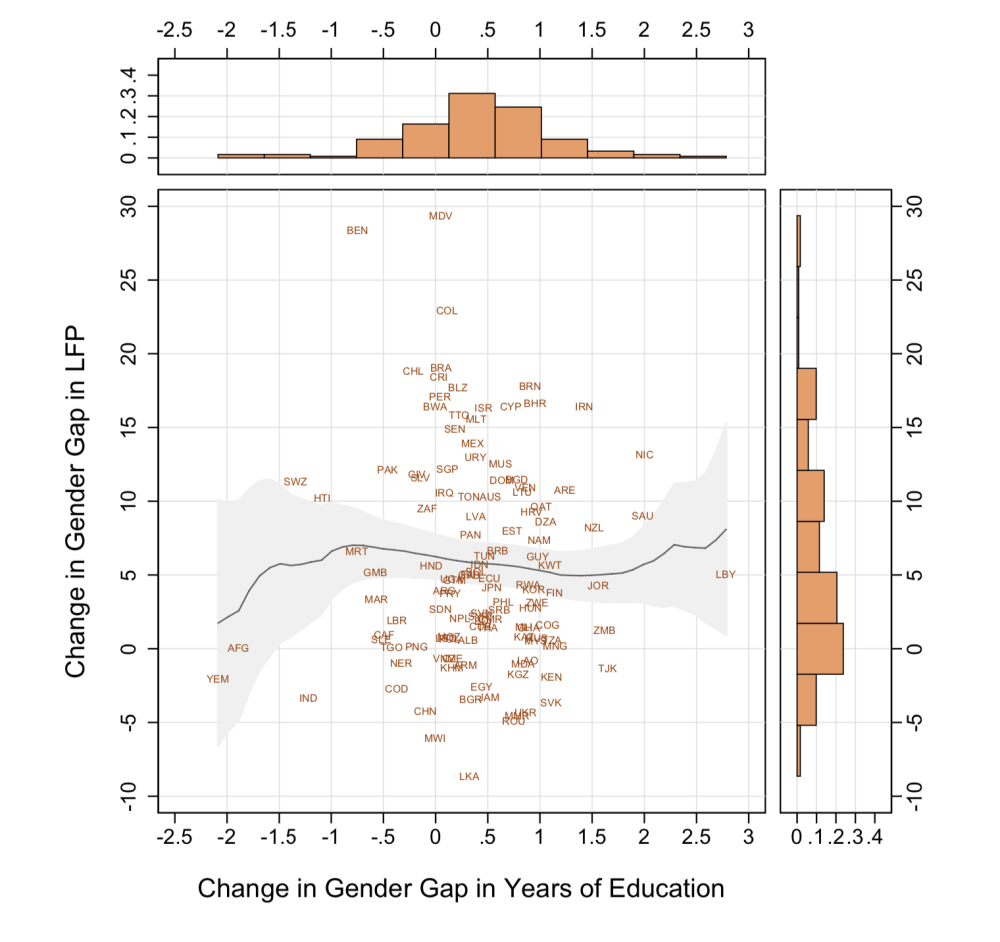

Lots of countries have seen reductions in gender gaps in education. Lots of countries have also seen increases in women’s labor force participation. But as the figure above shows, there is no clear association between the two. This doesn’t mean that education doesn’t matter: Education matters, and education is a human right. But it does mean but education alone won’t end economic inequality by itself.

What else should I read about this?

We document where the world has been and where countries are moving in terms of gender equality in education. Here is some other work in this area from the last couple of years. (For more references, check out our paper.)

-

What about gender gaps earlier than 1960? Bertocchi and Bozzano take a longer view in their 2019 paper.

-

What can countries do about these gaps? Evans and Yuan explore the most effective interventions for improving girls’ education in their paper.

-

How much does education really improve outcomes for girls? Psaki and others examine impacts on sexual and reproductive health; and Mensch and others examine impacts on maternal and child health.

-

What explains these changes in the gender gap? Bossavie and Kanninen test two hypotheses.

-

Beyond education, how do we boost women’s economic empowerment? Buvinic and O’Donnell review a range of interventions (published; open-access).

The order of authors for this blog post and the accompanying paper were randomly assigned. Ray and Robson explain why this is a good idea, and the American Economic Association provides a tool that makes it easy.

If some of the figures from this blog post look familiar, Pam Jakiela and Susannah Hares showed some initial analysis with these data last year.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.