When NATO forces entered Afghanistan following the attacks of September 11, 2001, much of the country’s infrastructure, as well as its public institutions and underlying social fabric, had been destroyed by more than two and a half decades of conflict. At the time, landmines were still killing an average of 40 Afghans a day.

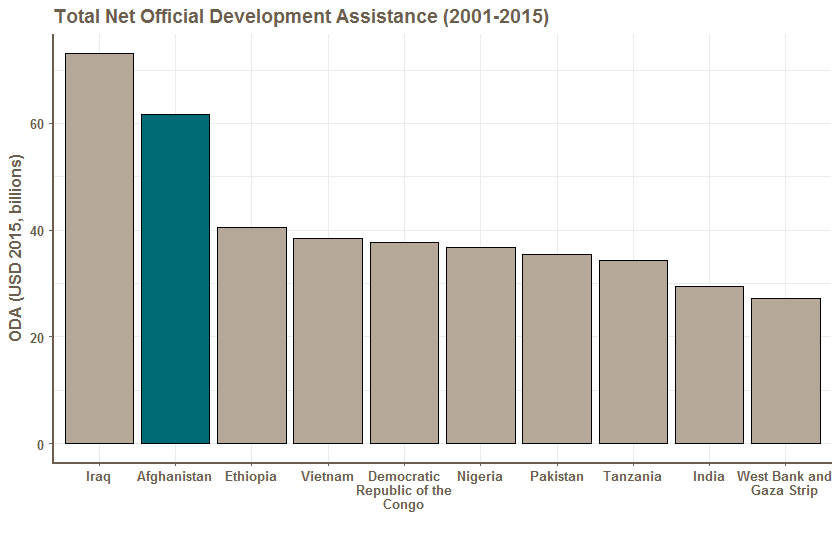

Over the last 15 years, the international community, led by the United States, has invested massive resources in an attempt to transform Afghanistan into a more stable, modern, and prosperous country. While most of these resources were directed towards military support, a good chunk went to supporting economic development. In fact, Afghanistan has received more official development assistance than any other country since 2001, except for Iraq (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: World Development Indicators, World Bank

Despite the often well-founded pessimism attached to the international effort in Afghanistan, the average Afghan, and particularly the average Afghan woman, is better off today than he or she was in 2001, according to the data. Consider the following advances made since that time:

- Income per capita has more than doubled (though the country's per capita GDP of roughly $600 remains one of the lowest in the world).

- Access to primary healthcare has increased from 9 to 82 percent of the population.

- The percent of women attended by a skilled care provider at birth has risen from 14 to over 50 percent.

- The number of Afghan children attending school has increased from less than 1 million to 9 million and the percent of students who are girls has increased from roughly 10 to 40 percent.

- The country had its first democratic transfer of political power in 2014, with both men and women allowed to vote in the election.

These important gains are at risk, as the security situation in Afghanistan has deteriorated over the last several years following the drawdown of foreign troops. Today, the Taliban control 11 percent of the districts in the country and contest an additional 29 percent.* They have also ramped up the number of attacks in major cities. As a result, civilian casualties increased to 11,418 (3,498 deaths and 7,920 injuries) in 2016, the highest on record. At the same time, the country’s ability to provide social services is under strain due to the growing number of the internally displaced persons, which climbed to 1.4 million in 2016, and includes a large number of former refugees who have been repatriated from Europe, Iran, and Pakistan.

The recent announcement by the Trump administration that it would modestly increase the number of US troops operating in Afghanistan improves the chances of achieving stability. However, meeting this goal will also require the international community and the Afghan authorities to learn from past mistakes.

Two steps forward, one step back

Development in Afghanistan has been uneven and the rate of progress has generally tracked the evolution of the security situation. Starting from an extremely low base in 2002, the country achieved rapid progress early on, as technical advisors from USAID, DFID, the IMF, and World Bank helped the government rebuild key institutions essentially from scratch, and as donors implemented projects focused on providing basic health and education services.

During this time, the country enjoyed a brief respite from conflict. By the mid-2000s, however, the Taliban had begun to reassert itself in the south. The group’s resurgence was facilitated in part by the Bush administration’s decision to divert attention and resources to Iraq, and in part by the inability of the Afghan government to exert control and provide services in the provinces. In 2009, the United States and its allies responded to the growing insurgency by settling on a military strategy that relied on a surge in troops and aid aimed at dislodging the Taliban and winning the hearts and minds of rural Afghans.

The strategy temporarily supported growth and allowed the government to regain a tenuous hold on territory but did little to address some of the underlying problems in the country that continue to fester today, including widespread corruption and opium production. When the Obama administration announced a staggered troop withdrawal beginning in 2011, it soon became clear that many of the security and economics gains achieved were illusory.

Deteriorating security and political uncertainty ahead of the 2014 election led to a collapse in private investment and a sharp slowdown in growth, which fell from 14.0 percent in 2012 to 1.3 percent in 2014. These factors in turn contributed to an increase in the poverty rate and a 3x increase in male unemployment between 2011 and 2014. Unemployment is particularly problematic in Afghanistan because of the country’s “youth bulge”: roughly 63 percent of Afghans are under 25 years of age. The Taliban has taken advantage of the lack of employment opportunities for young men to lure potential recruits with salaries twice as high as those offered by the Afghan army.

Protecting what’s been gained

Most of the improvements noted above were made in the period 2001-2010. But the current decade has been cruel to Afghanistan. In a 2016 poll conducted by the Asia Foundation, 66 percent of Afghans believed that the country was going in the wrong direction, the lowest level of optimism since 2004. The question now is whether the Afghan authorities and international community can arrest the country’s recent slide, stabilize security, and build on the progress made in earlier years. Addressing the long-standing problems that have prevented a lasting peace from taking hold will require changes in behavior on the part of both donors and the government.

These challenges include:

- Reducing corruption. Afghanistan was ranked 169 out of 176 countries in Transparency International’s 2016 corruption perceptions index. The belief that public servants are corrupt has sapped popular support from the government and provided an opportunity for the Taliban. But the Afghan government does not hold all the blame. The international community pushed billions of dollars of aid into a country that lacked public sector capacity, a strong judiciary, and robust financial supervision—and then often failed to monitor where funds went. More strikingly, many actors in Afghanistan, including the US government, frequently paid off Afghan elites and power brokers to win their allegiance and gain information. The result was a country awash in dollars with little oversight about how they were spent.

- Taming opium production. Afghanistan supplies roughly 90 percent of the world’s illicit opiates and the opium trade fuels both corruption and the insurgency. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime estimates that potential opium production increased by 43 percent in 2016, despite the more than $8 billion spent by the US government in counternarcotic programs in the country since 2002. Efforts at eradication have stalled in recent years, as the Taliban presence in poppy cultivating provinces has increased, and there is currently no credible strategy to deal with the problem that does not require improved security.

- Reaching a political settlement. Both Afghan authorities and US officials now recognize that the terminating the war in Afghanistan will likely require some form of political settlement for two reasons: first, the United States does not have the appetite to wage a full campaign in the country again and second, even if it did, the Taliban has proven repeatedly its ability to bounce back. Indeed, US Secretary of State Tillerson has stated that the administration’s new strategy is to put enough military pressure on the Taliban to bring them to the negotiating table. Any political settlement would have to involve Pakistan, which continues to provide safe haven to insurgents.

- Reducing aid dependence. Although clearly a secondary goal compared to enhancing security, the Afghan government must find a way to reduce its dependence on foreign aid. A recent World Bank report suggests that the country will not achieve fiscal sustainability—defined as occurring when domestic revenues cover operating expenditures—until well after 2030. Until then, the country will continue to rely on donors to cover most of the costs associated with security and development. Enhancing sustainability will require taking steps to both enhance growth and improve revenues, which start from a very low base of 10.5 percent of GDP.

A shot at stability

The international community’s inability to secure a lasting peace in Afghanistan after 15 years of engagement has naturally produced impatience in both Afghanistan and its partner countries. However, a full withdrawal of international assistance would leave the development gains made since 2001 at the mercy of the Taliban. The continued presence of US troops in Afghanistan preserves the possibility that the Afghan government can make inroads in governing—and that a fair political settlement, which pacifies the Taliban without giving them the power to roll back the freedom of women, for example, can be reached. In doing so, it can help to improve the outlook for one of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable populations.

*Focusing on territory gains alone overstates the Taliban’s advances. While the number of districts controlled by the Taliban has risen in recent years, a stalemate has set in more recently, and most of these districts are sparsely populated: 21.4 million Afghans live in districts controlled by the government, while only 3 million live in districts controlled by the Taliban.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.