Recommended

In a world of stagnating public aid, limited fiscal space, and rising public debt in low-income countries (LICs), can they realistically expect to rely more on private finance from foreigners? What does the evidence suggest? Our new paper looks at recent cross-border private capital inflows to LICs. You might be surprised at what has happened since the global financial crisis.

Foreign private investment has caught up to foreign aid as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) for the median LIC

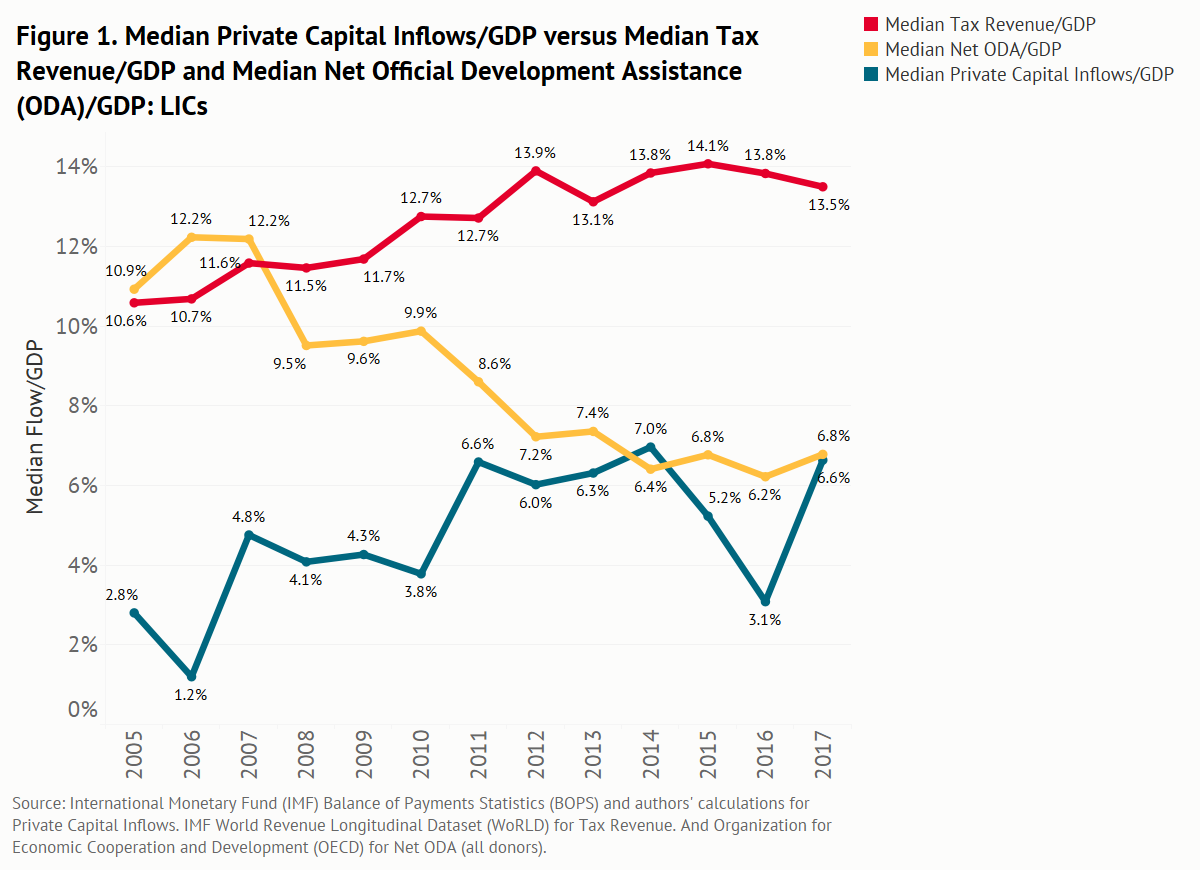

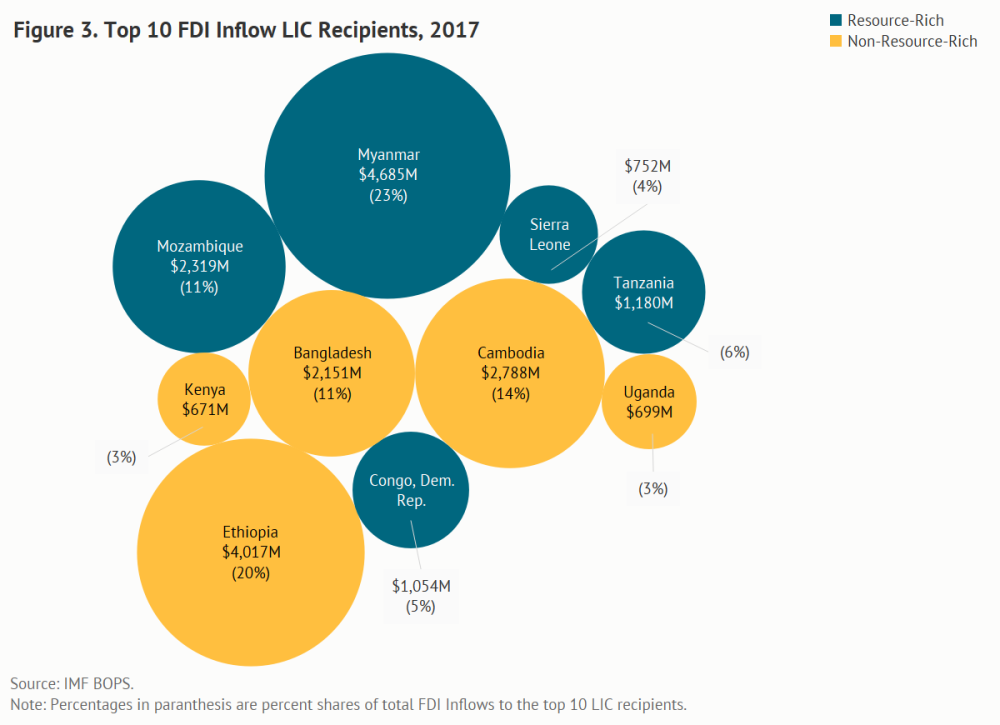

For individual LICs, external private capital is an important and growing source of finance (Figure 1). The global financial crisis has not had a lasting, dampening effect on private inflows to LICs—quite the opposite. The median ratio of inflows/GDP reached new highs—over 6 percent from 2011 on—with the exception of 2015 and 2016 when the downturn in global commodity prices and tightening US monetary policy pushed short-term capital inflows lower. Foreign direct investment (FDI)—which makes up most of the inflows to LICs—has been stable and resilient throughout the post-crisis period. In contrast to higher median private capital inflows and tax revenue as a share of GDP, median foreign development aid has dropped by almost half as a share of GDP since 2006.

It’s not all about natural resources

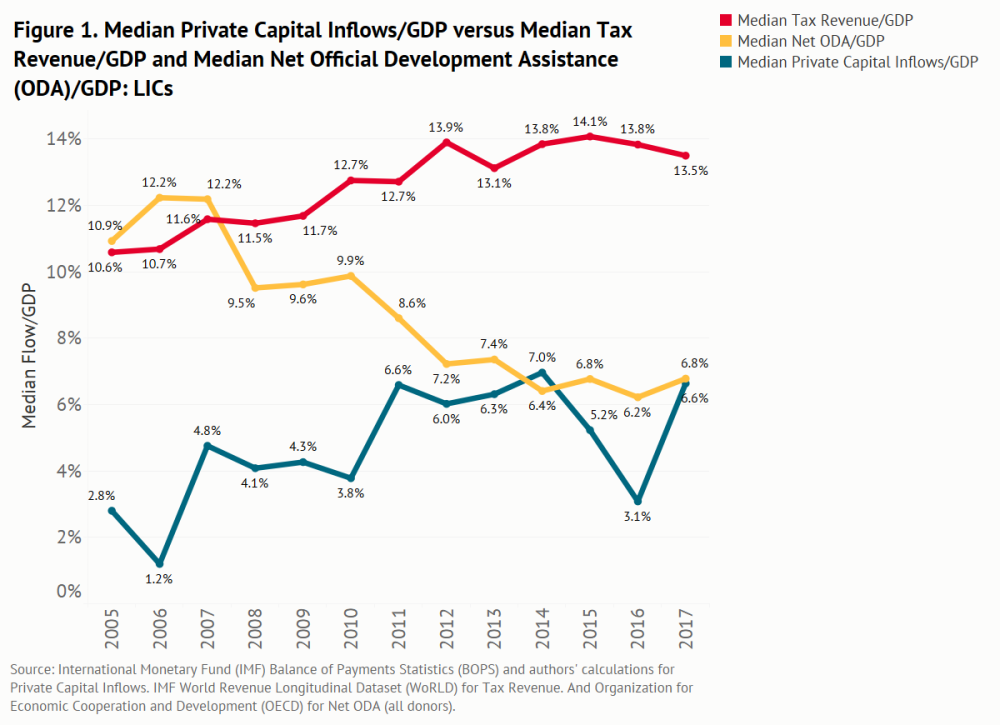

Inflows are not all captured by resource-rich LICs (Figure 2). In 2017, more than half of capital inflows to LICs went to non-resource-rich LICs (Figure 2.1). Commodity prices appear to have influenced total inflows into both set of countries. But zeroing in on FDI alone shows more volatility in flows to resource-rich LICs. FDI to non-resource-rich countries shows a steady upward march throughout the period (Figure 2.2).

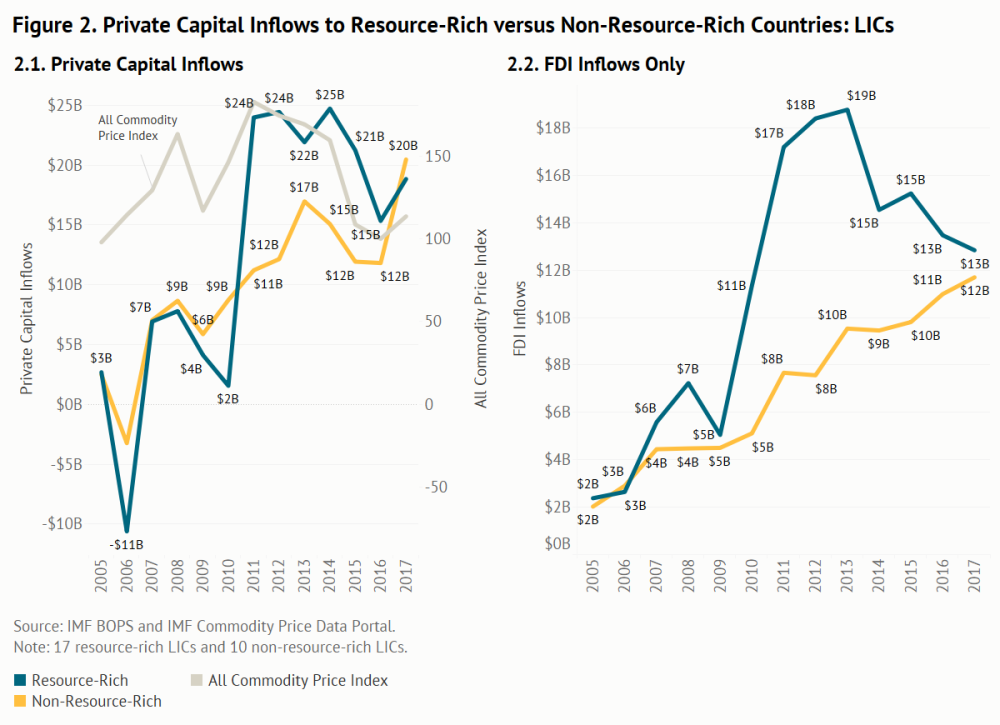

The top 10 LIC recipients of FDI in 2017 are equally divided between resource-rich and non-resource-rich countries (Figure 3).

Policies make a difference

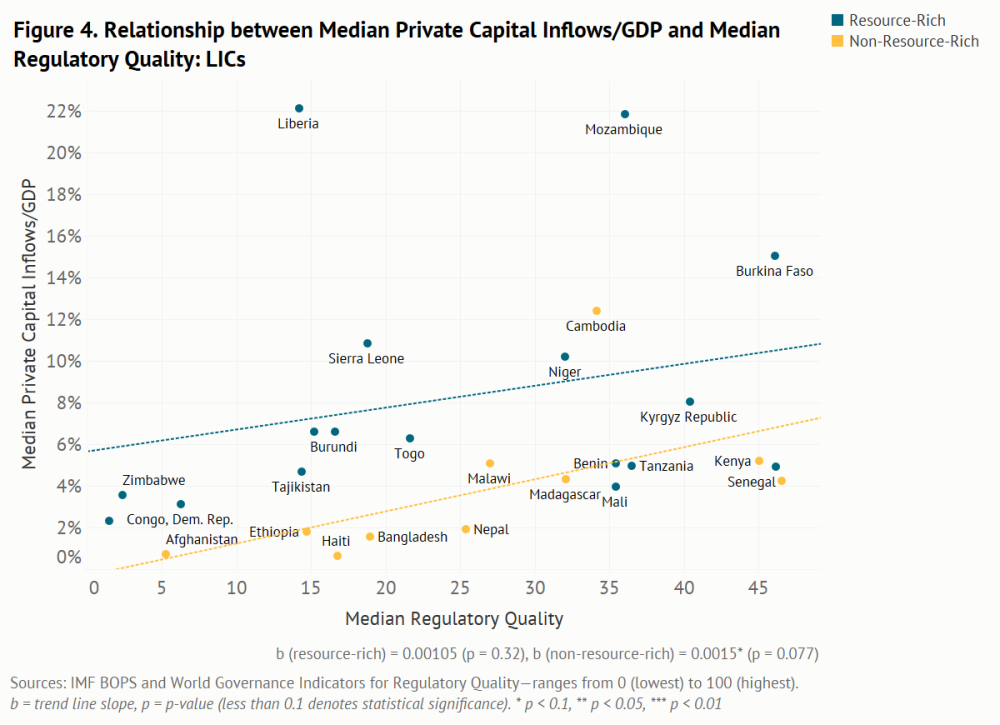

Investment climate policies have a stronger association with inflows in non-resource-rich than resource-rich LICs. Figure 4 shows a significant positive relationship in non-resource-rich LICs between capital inflow ratios and a broad measure of investors’ perceptions of regulatory quality that covers policies for taxes, trade, starting a business, price controls, competition, and labor markets. The relationship is not significant for resource-rich LICs, where investment decisions are more likely driven by policies specific to resource extraction. Non-resource-rich countries are showing that their resource endowments no longer determine their destiny. Their policy choices matter.

China is a growing investor, not just a lender

We also see an interesting shift in the sources of FDI over a relatively short period of time. China more than doubled its stock of FDI in Africa between 2011 and 2016 (Figure 5)—and the amount is now closing in on that of large traditional direct investors like the United States, United Kingdom, and France. Much attention has been paid to China’s role as a creditor to Africa; its role as a rapidly growing direct investor has received less attention.

LICs need to think about how to spread the benefits of foreign investment more widely in the economy

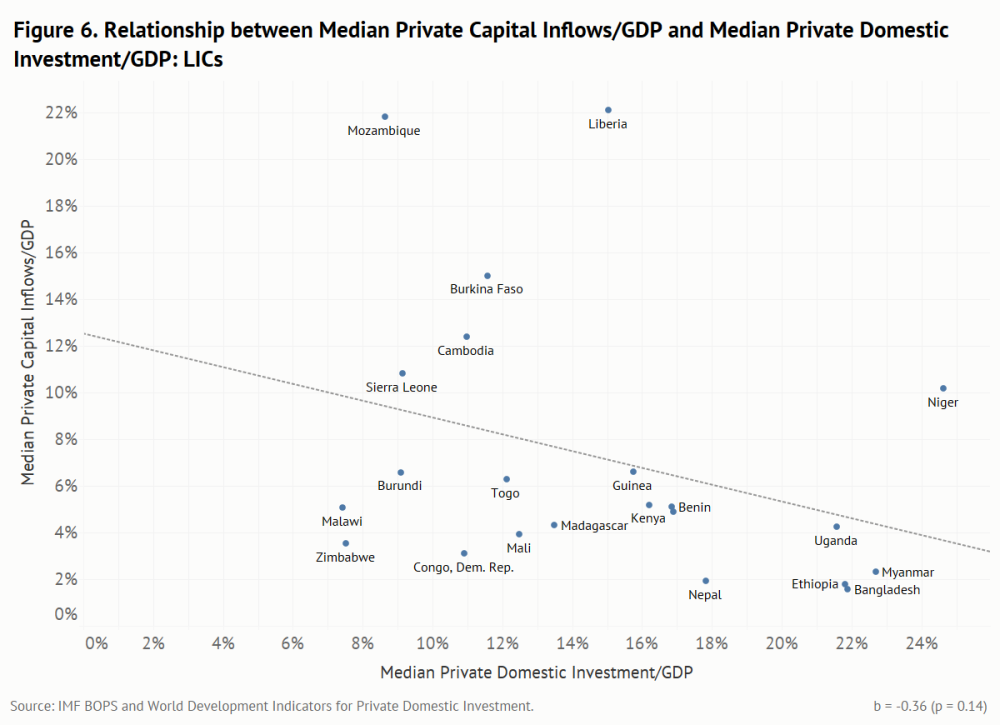

Given the importance of private capital inflows in LIC economies, it is worth examining whether higher inflows are positively related to domestic private investment. Private inflows might spur complementary domestic private investment, as in the example of FDI by a foreign auto company catalyzing the growth of domestic parts manufacturers and auto sales companies. We find that foreign and domestic private investment do not necessarily reinforce each other (Figure 6). That raises concerns. It contrasts with lower-middle-income countries where private foreign and domestic investment/GDP ratios are significantly and positively correlated. The apparent lack of complementarity between foreign and domestic private investment may point to problems related to investment enclaves. Or, in cases where the state dominates LIC economies, the state could be crowding out local private investors.

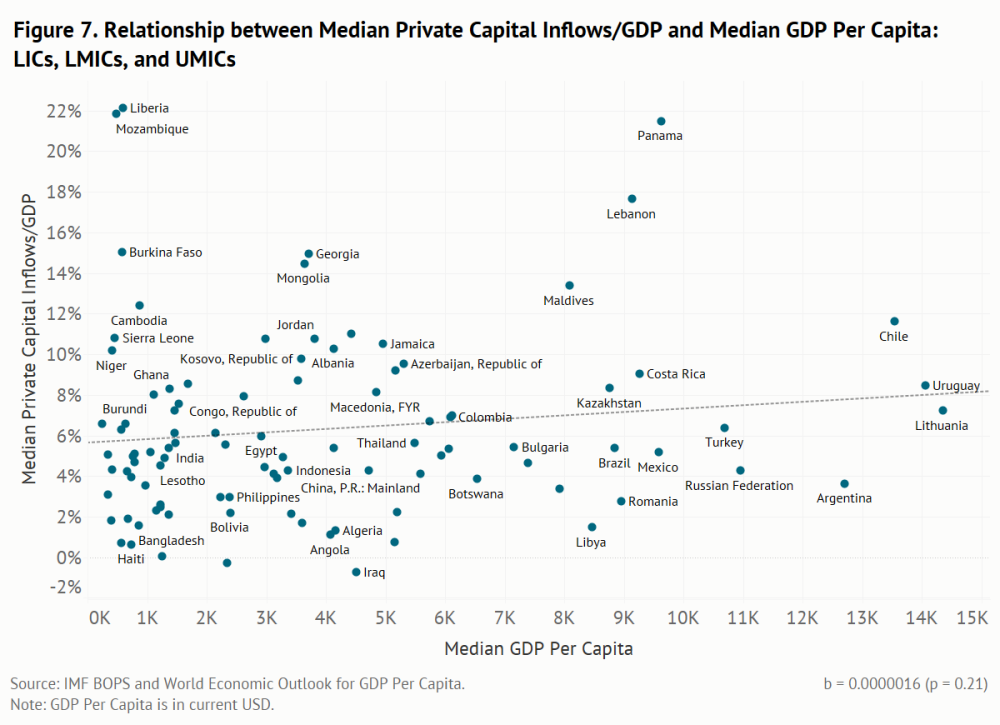

Country per capita income is not a good predictor of private capital inflow ratios

Figure 7 shows no relation between median inflow ratios and median country income levels, meaning that as LIC move into higher income categories, it should not be presumed that private inflow ratios will also rise.

That has important implications for donor policies on graduation from concessional resources, which often assume private finance will replace declining aid.

In short….

Much of the news for LICs is encouraging, and some of it flies in the face of conventional wisdom. For LICs, private inflows are an important and growing source of finance. The inflows are not all captured by resource-rich LICs. Increasingly, policies, not just resource endowments, shape LIC destinations for foreign capital. The relation between median capital inflows/GDP and median regulatory quality is significantly positive for non-resource-rich LICs. While many have focused on China’s role as a LIC creditor, China is also playing a key role in diversifying sources of FDI in Africa.

But there is also not-so-good news. More private foreign investment does not necessarily mean more private domestic investment in LICs. And private inflow ratios do not predictably rise with country per capita income. That means that donors reducing concessional finance as countries move out of LIC status should not assume private inflows will take up the slack.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.