Recommended

The UK’s development agency, DFID, has stated that it views research as the best way to spend aid and that it intends to place high quality research central to its aid strategy. We think that is great: innovation and the spread of knowledge play a substantial role in improving people’s lives and there is a strong argument for it to be an aid priority. But in a new paper, we find significant problems with the way that UK aid is being used to back research: a huge ramp-up in support has largely gone to fund opaque, unfocused research in UK universities. There are better approaches.

The UK is a top R&D donor—but where’s the money going?

The UK government spent a total of £14 billion in official development assistance (ODA) in 2017. (In this blog we refer to net ODA figures, to be consistent with the total ODA budget. Gross figures are slightly higher as some loans for R&D were repaid during 2017, but the broad story does not change.) Bilateral research and development ODA was £737.9m, which accounts for 8.3 percent of bilateral aid spending. That means the UK reportedly spends as much as the next 15 donor countries combined on R&D and reflects a recent trend to much higher spending that began in 2014. (Our data in this blog represents an annual snapshot of R&D spending. Research projects are usually multi-year; the average length of currently active DFID research projects is 6.7 years.)

The UK Department of Health (DH)’s R&D spending increased tenfold from 2016 (£5.1m) to 2017 (£51m), but most of the increase since 2011 is due to a sharp uptick in spending by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), whose research ODA increased fivefold between 2012 and 2017 (Figure 1). BEIS is responsible for UK science policy and for funding basic research and is central to the government strategy to be an R&D leader. It oversees UK research councils; administers the £735m Newton Fund, whose mandate is to develop science and innovation partnerships that promote the economic development and social welfare of partner countries; runs the £1.5bn Global Challenges Research Fund, whose aim is “to ensure UK science takes the lead in addressing the problems faced by developing countries, whilst developing our ability to deliver cutting-edge research”; and oversees R&D conducted by UK higher education institutions.

Figure 1. BEIS has led the charge in expanding UK research aid

Source: Data from DFID, CRS (see paper for notes)

Medical research is a high priority in UK aid, comprising 34 percent of all research aid. This reflects the government’s goal of pursuing a greater focus on health systems and leading a major new global programme to accelerate the development of vaccines and drugs to eliminate the world’s deadliest infectious diseases. This category also contains spending by the £1bn Ross Fund, whose work focuses on developing products for infectious and tropical diseases and implementation programmes for malaria and neglected tropical diseases.

Although health was the specific sector to receive the most funding directly, slightly more research ODA (41 percent of the total) went to “research / scientific institutions,” which is managed mostly by DFID and BEIS. The majority of projects delivered by BEIS are classed in this way yet, the OECD’s Creditor Reporting Systemguidelines for classifying projects as “research/scientific institutions” includes “when sector cannot be identified.”

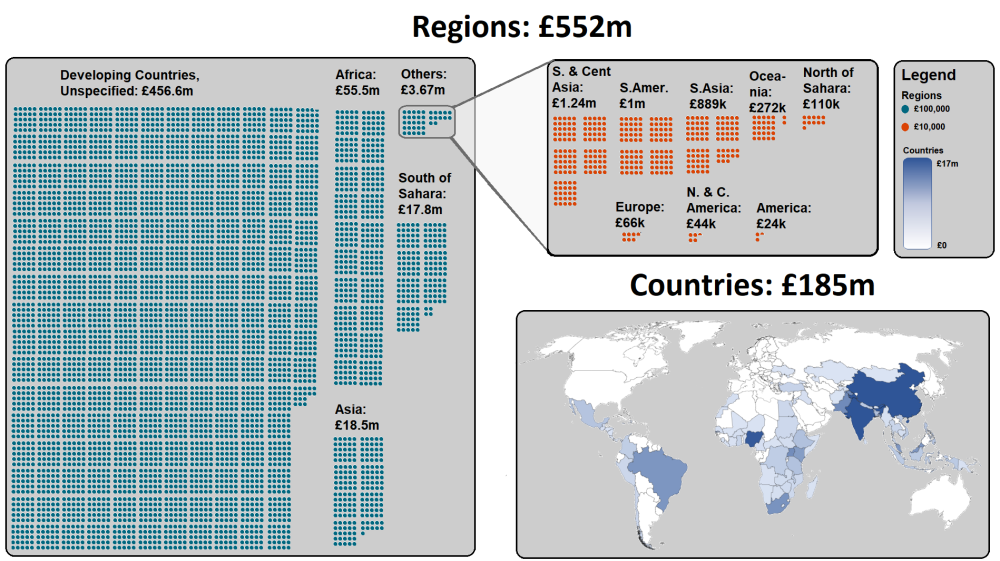

Along with considerable opacity regarding the sector of research, UK aid spending on R&D is weak on defining target beneficiaries: £457m of £738m of research aid goes to “developing countries, unspecified” (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Most aid goes to unspecified destinations

Source: DFID data, XKCD Chart concept

Tied aid in disguise?

A very large share of the unspecified projects appears to be UK-based research and is delivered through UK universities. If this allocation is made without competitive tender, then it is a form of tying aid, which has been shown to reduce the effectiveness of aid by favouring service providers from the donor country (a noted goal of BEIS) rather than the ones best qualified to deliver the service. And at least some of the growth in research aid appears to be pre-existing UK university research projects being reflagged as aid in light of the legislated commitment to spend 0.7 percent of gross national income on aid. This raises questions about whether the primary purpose of these projects is poverty reduction, a requirement for ODA.

Total global public and private R&D in 2018 was around £1.5 trillion, meaning that UK research aid of £738m was just 0.05 percent of global R&D. In order for such a tiny fraction to have a significant impact, it has to be targeted on the specific challenges of developing countries where the payoff to research is likely to be the highest, and money should be spent where it can be used most effectively.

In that regard, there are things to admire in some of the UK spending on R&D for global development. A large share goes towards health research, which can rank among the most cost-effective health programmes known (including basic vaccination and micronutrient interventions). The UK has also been a leader in supporting multilateral approaches to research on development challenges. For example, it is a major contributor to the $1.5bn Advance Market Commitment for Vaccines fund, which was designed to incentivise vaccine manufacturers to focus research on a variant of the pneumococcal vaccine suitable for tropical countries based on guaranteeing demand for the product developed. Similarly, DFID has committed to a budget of £50.8m for the Global Innovation Fund, which invests in a portfolio of projects that create and scale up new innovations for development.

But it appears that a considerable proportion of UK ODA R&D is a form of tied aid that misses opportunities for overseas capacity building and is poorly focused on key development challenges. The UK should stick to its commitment to avoid all tied aid and allocate most research spending by open tender to address priority development issues, preferably through multilateral channels, with considerably more support for researchers in developing countries.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.