How should governments of poor countries respond to the COVID-19 crisis? Framing this question as a trade-off between the health and socioeconomic consequences of stricter health measures such as lockdowns may be counterproductive in rich countries, but is hard to avoid in poorer ones.

Trade-offs are even harder to assess because of the lack of data—and the rapid rate at which data becomes obsolete as the crisis evolves. For instance, in addition to the vital (and often missing) information on true rates of infection in the population, policymakers also lack key socioeconomic information:

How is the crisis impacting the population economically? Are they already feeling the consequences of social distancing measures and the global economic slowdown?

How is the population coping with health measures? Are they fleeing urban centres? Do parents use TV or online courses to support the learning of their children while schools are closed?

Do people know about COVID-19 and do they comply with mitigation measures?

Are people supportive of stricter measures, such as lockdowns? Do they trust the reaction of the government?

We believe that answering quickly these questions could help to have a better response for COVID, so we piloted a mobile phone survey on 1,000+ respondents in Senegal in partnership with the Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Économique et Social (CRDES) to provide some answers. We published the results of the survey yesterday and we are now publishing some of the key findings of the study.

Why Senegal?

Senegal is likely to be greatly impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. It was one of the first African countries to detect a case (on March 2) and it now has 442 cases and six deaths. Seven percent of Senegal’s economy relies on international tourism, which stopped entirely when borders were closed on March 19. Migrant remittances make up 9.3 percent of its GDP, and Senegalese migrants in Spain, France, or Italy might not be able to send money home in the coming months.

Senegal has adopted a list of strict social distancing measures to slow the spread of COVID-19, but has not decided to impose a lockdown yet. On March 14, the president, in consultation with medical experts, banned public gatherings and closed schools, kindergartens, and universities. Since March 19, travel between regions of Senegal has been heavily restricted and religious sites were closed on March 20. Since March 23, a state of national health emergency has been in place and a curfew is in effect from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. These measures are likely to affect the economy and the government has put in place an emergency plan of 1 trillion CFA francs (seven percent of its GDP or about $1.6 billion), including 69 billion CFA francs for emergency food aid.

What did we learn?

Our survey includes questions on the economic impacts of the crisis, mitigation measures, perception of government action, education, and migration. We have made all our data available here alongside the reports in French and English. The survey was conducted between April 7 and 13 by interviewers through random digit dialling and we use post-stratification and sampling weights to make our sample representative of the Senegalese population. The description of the methodology can be found at the end of the report.

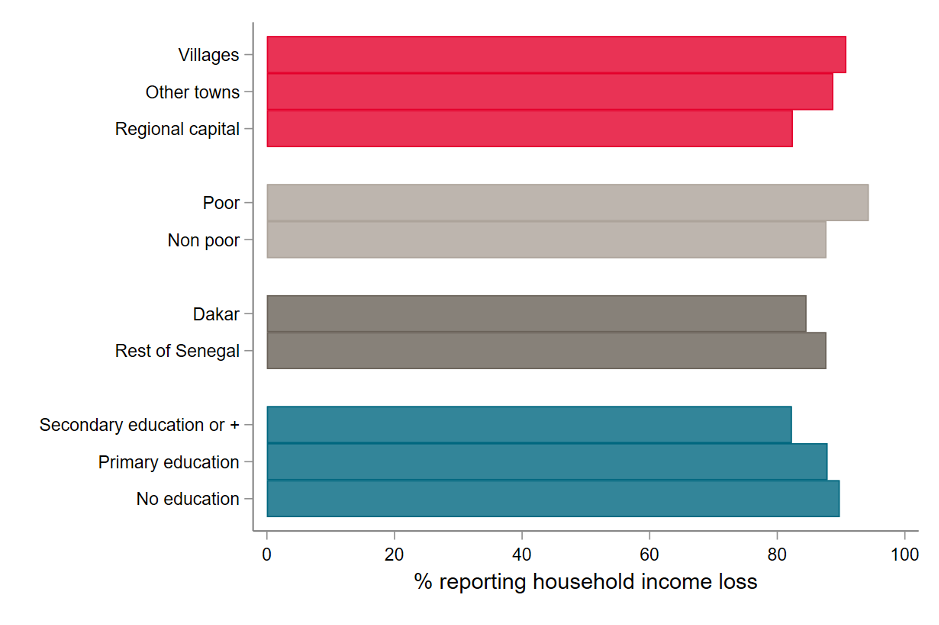

More than 85 percent of Senegalese have seen a reduction in income

Senegalese are suffering economically: 86.8 percent of respondents already reported a loss of income. There is some variability in this figure with poor people, people living outside Dakar and people with low levels of education more likely to report an income loss.

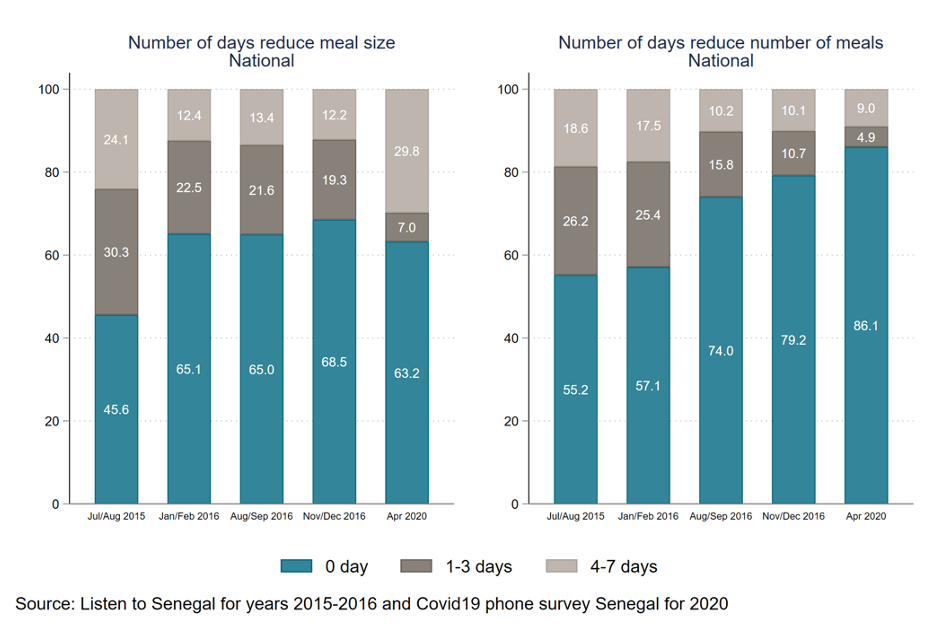

Over a third are eating less food

We also collected data on food security asking respondents how many days their household had to limit the size of meals or cut in the number of meals per day during the last seven days. The same indicators had been collected in 2015-16 in a nationally representative phone survey in Senegal (“Listen to Senegal”). Our data show that the number of people reporting limiting the size of their meals four to seven days a week is relatively high, especially as the lean season has not started yet (June-July). People who responded that they have experienced a loss in income are 17 percentage points more likely to report that they limit the size of their meals.

We also collected data on food prices in order to track inflation in follow up surveys. At baseline, 45 percent of respondents complain about an increase in the price of rice (only one percent report a decrease) and the number is higher in rural areas.

Almost all respondents had heard about coronavirus and people report high compliance with mitigation practices

Close to 90 percent of people report that they have stopped going to the mosque. This was one of the most contentious measures taken by the government, leading to protests in Dakar. Thirty-nine percent of respondents said that they wear a mask, even though it was not recommended when data were collected (Senegal made wearing masks outside compulsory on April 20, after the survey was in the field). This is a good sign for Senegal: a high adherence to mitigation measures could help slow the spread of the disease and avoid a lockdown.

The majority support a two-week lockdown

So far, Senegal has put strict measures in place such as closing places of worship or closing schools but has resisted locking down the country. We asked respondents if they would be in favour of a lockdown of two weeks to contain the spread of COVID-19. Seventy-two and a half percent of the population are in favour of this measure. Interestingly, the support for a lockdown is 19 percentage points lower among respondents who report an income loss but only slightly lower for poor people, suggesting that the actual experience of an income loss makes people worry about the economic consequences of the lockdown, rather than their level of income. If that’s the case, a worsening of the economic crisis could quickly turn public opinion against a lockdown.

The majority of the population is also supportive of the government, with 86 percent trusting the government to take care of its citizens and 87 percent finding government communication truthful. These figures are much higher than comparable figures collected in an online survey of 58 mostly high-income countries (the figures were 43 and 57 percent respectively in the survey).

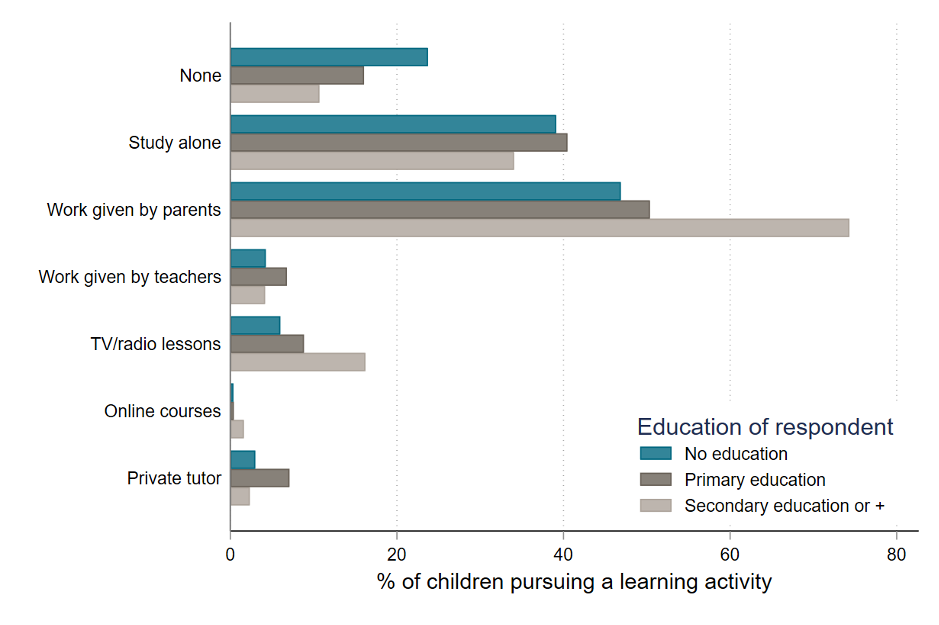

School closure is reducing learning and exacerbating inequalities

Thirty percent of children are not engaging in any learning activity. And, although most children receive support from their parents to continue learning, parental support varies across the levels of education of respondents (respondents are not necessarily the parents of children). Access to distance learning (TV or online) is low and also unequal.

Thousands have moved to rural areas

Since the beginning of the outbreak, European countries and the United States have seen movements of population from big cities to rural areas, which has increased the spread of the virus and oversaturated rural health systems. Similarly, many people left the capital Dakar in the last month and migrated to rural areas of Senegal. These large population movements might have contributed to the spread of the disease and risk saturating rural health systems.

What’s next?

We shared our report with the government and we hope that it can contribute to the policy response against COVID. Our plan is to follow up with the same respondents in a few weeks to see how the crisis continues to impact them. We want to see if the respect for mitigation measures remains high, how income and food security are evolving and we’re eager to ask more about education and healthcare.

Our experience in Senegal showed us that it is feasible to quickly and cheaply collect good quality data via mobile phones during the COVID-19 crisis. Other organizations are doing similar work (e.g. IPA in Bangladesh or the World Bank Living Standards Measurement Surveys) and coordination and collaboration between different actors will help collect data that are comparable between countries and help us learn from each other's experience. IPA has notably set up a research hub to track and coordinate phone surveys for COVID-19 responses in poor countries. We have posted our data and questionnaires online, and encourage others to do the same. Our data also provide a public good for other researchers as a benchmark of the current situation in Senegal. Our follow-up surveys should provide even more insights about the impacts of the COVID crisis in Senegal and we will share new results in future blog posts.

We are grateful to Samba Mbaye, Assane Sylla, Bamba Ndoye, Susannah Hares, Lee Crawfurd, and Justin Sandefur for their helpful contributions.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.