Recommended

In recent decades, concerted efforts to promote access, equity, and inclusivity in education have improved school enrollment for girls and marginalized and disadvantaged populations. Kenya is no exception: it has reached gender parity at the primary school level, and the Kenyan government has implemented various policies to promote gender equality in education and beyond. But there is a lot of work still to be done. Recent achievements mask disparities at the county level. In 18 out of 47 counties more girls enrolled in secondary school, while in 13 counties, disparities favor boys, with more boys completing high school and enrolling in tertiary education. Perhaps more importantly, even where it has been achieved—gender equality in access to education has not translated into equality in life opportunities for women due in no small part to restrictive social norms, some of which could be addressed through education.

The Kenyan Ministry of Education has a strong interest in using evidence to tackle these challenges and to improve gender mainstreaming throughout the education system. A recent review of the Ministry’s 2015 Education and Training Sector Gender Policy provided an opportunity to assess what has been working well or not within the policy to reduce gender inequalities in access, participation, and achievement at all levels of education. In partnership with CGD, the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC) has been leading research to assess the implementation of the education and training sector gender policy.

The research team collected primary data from Diploma teacher training colleges and 250 primary and secondary schools in the ten counties with the highest child poverty rates. Using this data, the APHRC team explored whether gender concerns are understood and integrated into various aspects of curriculum training and classroom practice in Kenya. This new research is being used to directly inform the Ministry’s policy review process and drafting of the new Education and Training Sector Gender Policy. A full report is forthcoming and key findings are discussed here.

Teacher training curriculum is lacking in gender inclusivity content

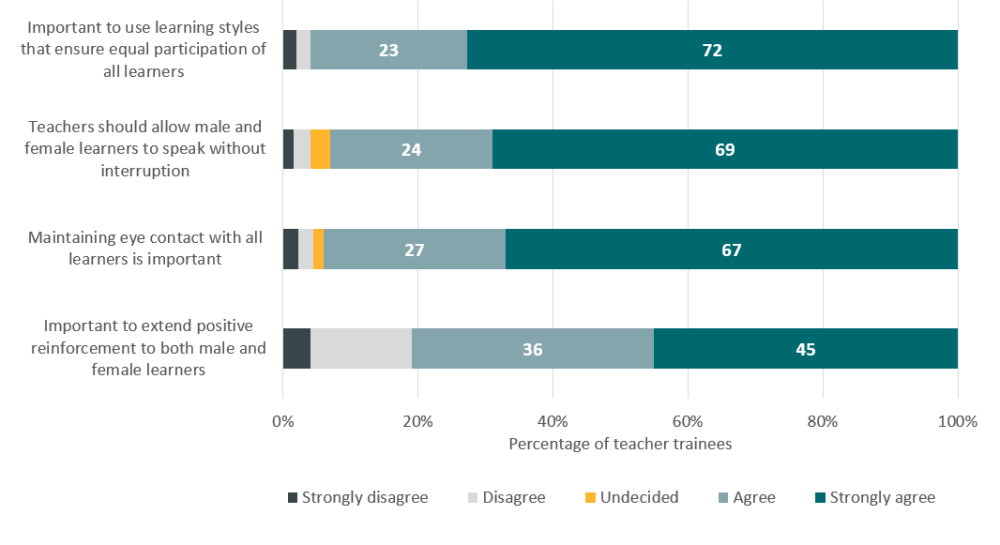

Teacher trainees seemed to have a relatively good understanding of the importance of gender-responsive communication and participation. The majority of trainees agreed that encouraging equal participation, extending positive reinforcement to girls and boys, and maintaining eye contact while allowing both male and female students to speak without interruption are all important (Figure 1).

The data, however, also suggests that gender biases are still prevalent among some teachers. For instance, around 15 percent of teacher trainees maintained that female students were better placed to write notes during group discussions, while male students were better placed to handle experiments or make presentations. Other teacher trainees (27 percent) held the view that the diverse learning needs of male and female students should not be taken into consideration during lesson planning.

Figure 1. Knowledge and attitudes on gender equitable teaching and learning practices

Source: Knowledge, skills, and attitude survey administered to 166 teacher trainees and 7 tutors from 7 Diploma teacher training colleges.

Qualitative interrogation revealed that the general knowledge and understanding demonstrated by the teacher trainees was mainly acquired from private training and general courses—such as child development and psychology of education. A review of the teacher training colleges’ curriculum found that gender mainstreaming pedagogical practice was not built into the pre-service curriculum as it is neither taught as a stand-alone unit nor integrated into other learning areas. Therefore, while knowledge in this area is not entirely lacking, more targeted instruction for teacher trainees could ensure that gender mainstreaming is consistently practiced in the classroom.

Teachers’ agreement over the importance of gender-inclusivity does not necessarily translate into action

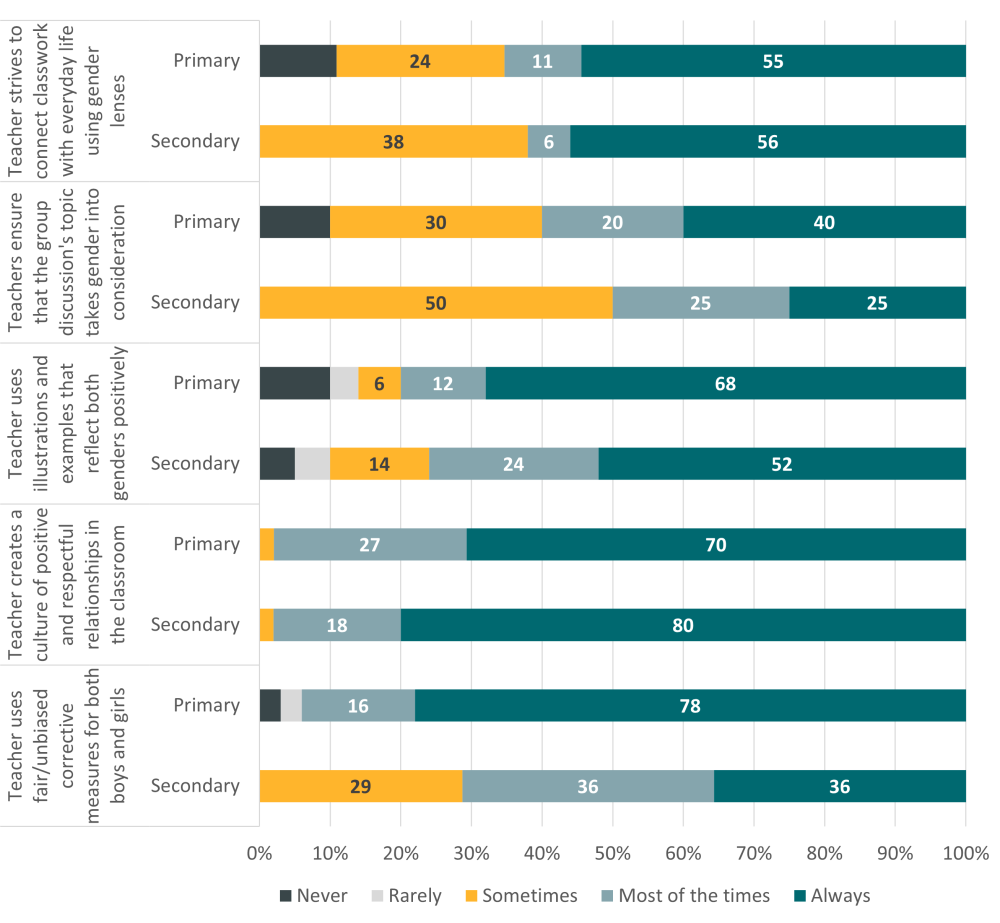

Data based on classroom observations revealed that teaching practices were not always gender-inclusive across the primary and secondary levels. For example, even though teachers agreed with the importance of equal participation, boys were called to participate significantly more times relative to girls during literacy and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) classes at the secondary level. Classroom observations also showed that only 60 percent and 50 percent of teachers at primary and secondary levels, respectively, ensured that the topics discussed during group activities took gender into account always or most of the time. Moreover, only 8 in 10 teachers frequently used illustrations and examples that portrayed both genders positively (avoiding the reinforcement of pervasive gender stereotypes) (Figure 2).

Furthermore, an examination of the classroom environment revealed that the majority of teachers created a culture of positive and respectful relationships for male and female learners. However, differences existed across educational levels in the use of corrective measures: 78 percent of primary teachers were found to use fair corrective measures or fair discipline approaches for both boys and girls all the time, while this was only the case for about 36 percent of secondary level teachers (Figure 2). The findings reveal that bigger changes in teaching practices are needed to ensure gender equality and inclusion in the classroom.

Figure 2. Proportion of teachers observed implementing gender-equitable classroom practices

Source: data based on classroom observations done in 103 mixed-gender primary and secondary schools.

Lack of guidelines on gender-based violence prevention is a major barrier to school safety and learning

Furthermore, the research identified a lack of easily accessible policies and guidelines on gender-based violence prevention: around half of school heads in secondary and primary levels respectively reported not having policies and guidelines to tackle gender-based school violence against students. Among those that reported having the policies and guidelines, 43 percent and 30 percent of primary and secondary school heads, respectively, could not show evidence of this. Addressing this is especially important considering that findings from the Kenya 2019 Violence Against Children Survey indicate that childhood sexual violence is a prevalent problem: 16 percent of females and 6 percent of males reported being victims before age 18. The research calls for the implementation of measures that effectively safeguard students, teaching, and non-teaching staff against gender-based violence.

Gender imbalances in school staffing and leadership are also a barrier to achieving gender equality

CGD colleagues Dave Evans and Alexis Le Nestour previously summed up the evidence on the impacts of female teachers on girls’ education; it’s a limited evidence base, but there are some positive indications of the impact that female teachers can have on learning outcomes as well as girls’ access to school and safety while in school. Policymakers in Kenya may want to consider attracting more female teachers, especially at the secondary school level in the Arid and Semi-arid regions.

Findings from the APHRC study indicated that teaching in the ten target regions remains a male-dominated occupation at the secondary school level, with a relatively equal proportion of male and female teachers at the primary school level and significantly more female teachers at the pre-primary level (Figure 3). The low participation of male teachers in early childhood education is mainly attributed to the lower salaries and the perception that early childhood teaching is “women’s work”. On the other hand, the higher proportion of male teachers in secondary schools can possibly be explained by the higher wages as compared to lower levels of schooling, schools that offer higher wages tend to attract more male teachers. This could also be attributed to the fact that acquiring a bachelor’s degree is a prerequisite for secondary school teaching (80 percent of teachers at the secondary school level have a bachelor’s degree) and existing educational barriers and patriarchal gender norms negatively affect women’s likelihood of completing tertiary education.

Figure 3. Proportion of teaching staff by gender at different levels of schooling

Source: Institutional questionnaire responded by 250 school heads regarding staffing by gender in primary and secondary school levels. Pre-primary data was obtained from school heads of pre-primary schools attached to the primary schools.

There were also proportionately more male teachers in all subject areas, particularly in mathematics and sciences. For instance, more than 90 percent of grade 6 mathematics teachers and form two physics teachers in public schools were male. Gender stereotyping might be an underlying reason for why fewer female teachers pursue mathematics and science careers. Studies point out that this gender stereotype is present even in young children who, for instance, attribute masculine traits to science or who, as early as second grade, demonstrate the stereotype that math is for boys.

Gender differences were also persistent in school leadership positions, with proportionately more male teachers as school heads and as heads of departments for various subjects. At the secondary school level, a huge 95 and 78 percent of school principals in public and private schools, respectively, were male, and more than two-thirds of heads of math departments were male. The low participation of females in leadership positions, especially in African contexts, is in part attributed to the negative stereotypes and social norms under which women are perceived as subordinate to men or not as good in leadership as men, as well as to the challenges women face in integrating family obligations with work responsibilities.

Gender gaps evident in absenteeism and choice of subjects

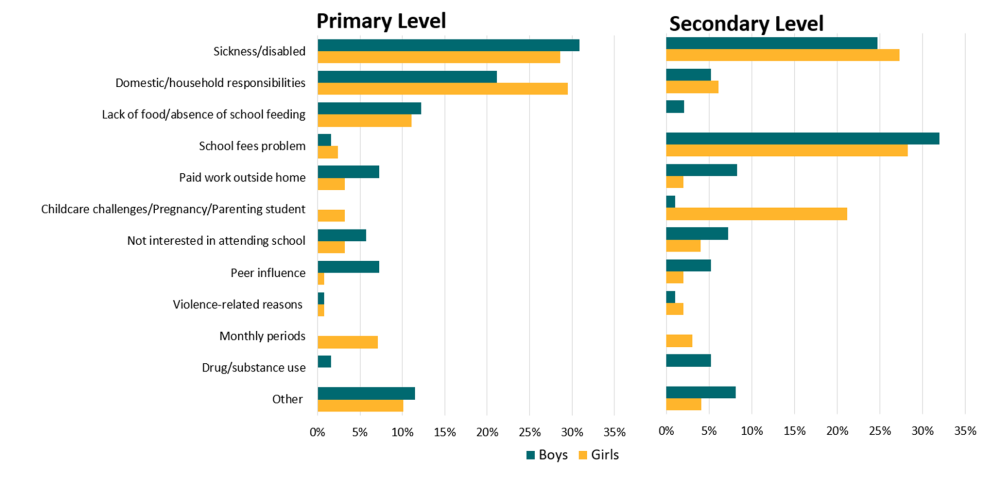

Study findings indicate that school attendance for boys and girls varied by the level of education (Figure 4). The main reasons noted for absenteeism for both boys and girls at the primary level were relatively similar (i.e., sickness, domestic responsibilities, and lack of food), while differences emerged at the secondary school level. The main reasons for absenteeism for boys were school fees problems, sickness, and paid work outside the home, whereas, for girls, in addition to school fees problems and sickness, pregnancy, and parenting responsibilities were the most common reasons for absenteeism. These disparities highlight the importance of implementing strategies to enhance regular school attendance while catering to the specific needs of boys and girls. Such strategies could include sensitization campaigns on the importance of school attendance, provision of universal health care insurance for students, school feeding programs, and institutionalized support for pregnant and parenting adolescents.

The findings also revealed that a higher proportion of boys preferred to select the more technical science subjects such as physics, while girls were more inclined to select humanities-related subjects like religious education. The general low preference to pursue certain subjects suggests that students are unlikely to choose certain career trajectories, such as STEM, an issue that disproportionately affects girls.

Figure 4. Reasons for absenteeism by gender and educational level

Source: Institutional Questionnaire. Sample of 250 school heads in primary and secondary schools located in the 10 counties with the highest child poverty rates in Kenya.

From evidence to policy-making: next steps

Across all educational levels there is some general awareness of how to implement gender-equitable practices in teacher training and classroom practice, and why this is important. However, this knowledge has to translate into practice and more targeted actions are needed to ensure gender mainstreaming in basic education.

The APHRC team is working with the Kenyan Ministry of Education to define specific actions for the new policy and to ensure that gender equality issues are consistently addressed and monitored in teacher training and basic education settings. Recommendations from APHRC have been considered by the Ministry of Education in the ongoing revision of the education and training sector gender policy. These include the implementation of actions ranging from coaching and capacity building of in-service and pre-service teachers, assessing teachers’ knowledge on the implementation of gender-responsive practices, supporting girls at risk of leaving school, and developing guidelines to address school-related gender-based violence.

Actions on these fronts will contribute to closing gender gaps in the education system and ensuring quality education for all.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Media Lens King / Adobe Stock