Even aside from their obvious, critical role in educating the next generation, there are a host of other reasons to care about teachers. A big share of government spending goes to teacher salaries. Teaching is a big share of professional opportunities in developing countries, particularly for women. The number of teachers is also expected to grow dramatically to accommodate the majority of children who still don’t complete secondary school in low-income countries. In a new working paper reviewing theory and evidence on teacher labor markets in developing countries (forthcoming as a chapter in the Routledge Handbook of the Economics of Education), we look at why should you care about teacher labor markets, from the interaction between the wages offered and recruitment numbers targeted by employers to the decision by students and workers to seek to become teachers. Here are three reasons why.

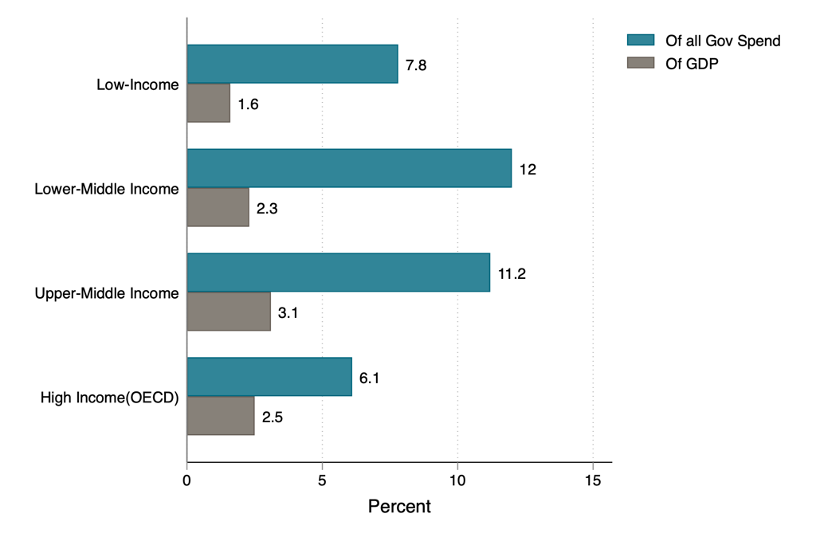

1. Teacher salaries make up around 10 percent of the entire government budget in poor countries

Never mind just education spending—teacher salaries make up a sizeable proportion of all government spending. If you care at all about the efficiency of government spending (and you really should), then you probably also need to care at least a bit about how teachers are recruited and managed.

Figure 1. Spending on teacher salaries as percentage of government budgets & GDP

Source: UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2018) for teacher compensation, World Bank (2018) for all other data. Regional groupings exclude countries that are OECD members. Teacher payroll data are from the most recent year available from 2013-2017. All other data are from the same year as teacher payroll data, or 2013-2017 average when that year is unavailable. All calculations weight by GDP within country groups.

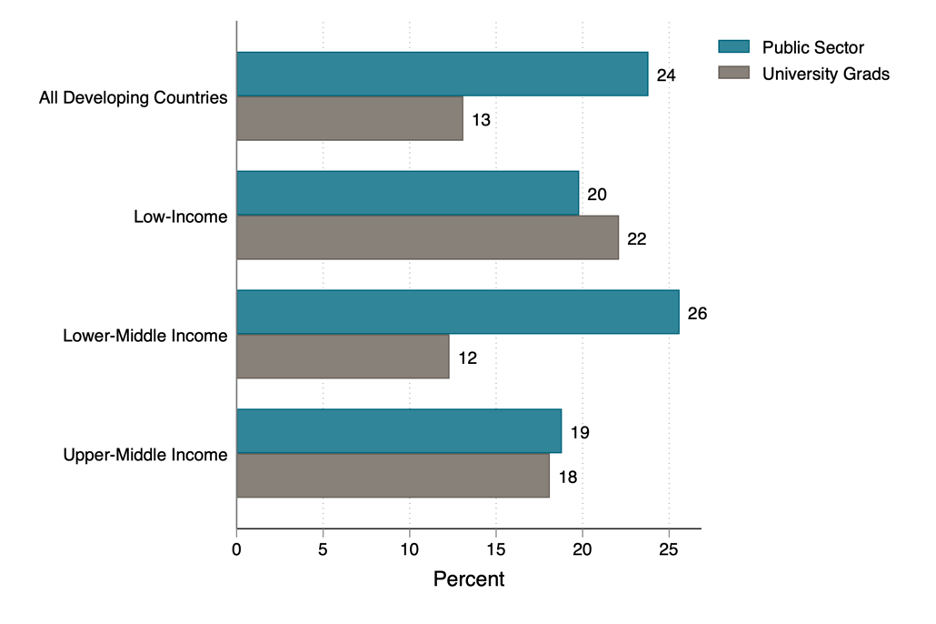

2. In low-income countries, one in five university graduates go into teaching

In countries with small formal sectors, teaching is an important source of employment. A large share of professionals, public sector workers, and university graduates are teachers. This is particularly the case for women, where over 40 percent of women in skilled jobs are teachers.

Figure 2. Teachers as a share of all professionals, public sector workers, and university graduates

Source: Minnesota Population Center (2018). Sample includes population census from the following countries: Armenia 2011, Belarus 2009, Botswana 2011, Cambodia 2008, Egypt 2006, El Salvador 2007, India 2009 (employment survey), Iran 2011, Mozambique 2007, Nicaragua 2005, Nigeria 2010 (household survey), Philippines 2010, Zambia 2010, Zimbabwe 2012. Sample limited to adults aged 25-55 in labor force (limited to employed workers in Philippines because labor force participation unavailable). Teachers includes teaching professionals at all levels. Public sector data available only for Cambodia, Egypt, El Salvador, Iran, Mozambique, Nigeria, and Philippines. All calculations weighted by population.

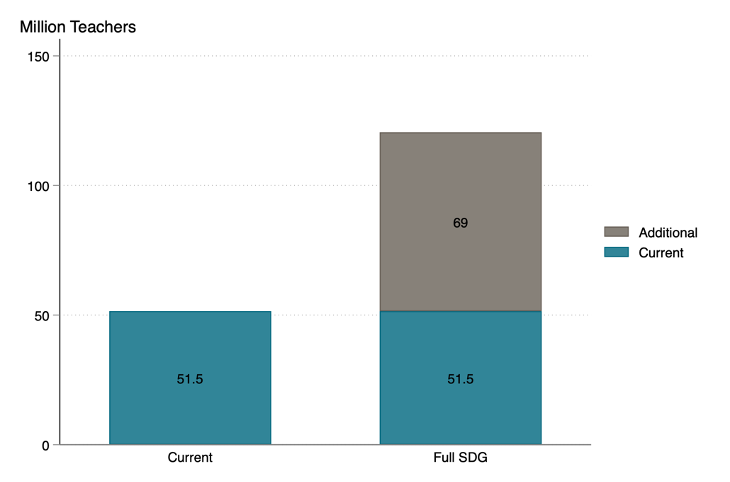

3. Achieving the SDGs will require a huge increase in teachers

There are currently around 50 million teachers in developing countries. UNESCO estimates that achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will require an additional 70 million. Whether such a dramatic rise is likely or not, what seems clear is that we should expect to see some increase in the number of teachers in the coming years. So it seems sensible to recruit and manage them in the most efficient way possible.

Figure 3. Increase in teachers needed estimated to achieve SDG4

How do teacher labor markets work?

The defining feature of teacher labor markets in a typical developing country is that they are highly segmented. Salaries in the public sector are typically much higher than in the private sector. In many cases several times higher. As a result, many teachers in the private sector are in effect queuing for their chance at a public sector job. (To their immense credit, in some countries many teachers in the public system are also in this queue and can teach unpaid for months or years before ever receiving a salary.) Many countries also have a formally segmented public system, with relatively high-paid permanent teachers working alongside lower-paid teachers on temporary contracts. Studies suggest that contract teachers can achieve the same (limited) learning outcomes as permanent teachers, which might suggest a way of improving efficiency, but in practice it has proven hard to maintain a permanent dual-track system without labor organisation to extend the same pay and rights to contract workers.

Perhaps the most important feature of teacher pay in the public system is not its absolute level but its structure. Compared to workers with comparable skill in other sectors, public teachers tend to be overpaid at low levels of seniority and underpaid at higher levels.

So what can we do to improve teaching?

Overall, the most promising avenue for improving the quality of education received by children is likely to be helping the teachers we already have to improve. But improvements could also be made to how teachers are hired and managed, which could prove particularly important if millions of new teachers do enter education systems.

Though teacher supply increases with wages, at least in the short term, there seems to be little effect of unconditionally higher pay on student learning. But most evidence comes from studies of short-term effects among existing teachers. Evidence on effects in the long-term, on the supply of new teachers, or on changes in non-pecuniary compensation is scarcer. What seems most important is that recruitment, promotion, and pay are in some way linked to actual performance on the job rather than just time served or seniority. The spectre of “performance-related pay” raises maybe as much political opposition as contract teachers, but this may in part be due to a caricature of a system based purely on high-stakes test scores. Even just thinking narrowly about pupil test scores, the majority of teachers in developing countries do actually support the idea. But in practice, especially in the many places where robust testing infrastructure doesn’t exist, a more sustainable and scalable solution might instead be one that trusts and empowers headteachers and local managers to make decisions about teacher pay and recruitment based on their judgement.

How has coronavirus affected teachers?

Of course, schools in nearly all countries in the world have been closed for at least some portion of 2020. While we don’t have a comprehensive picture of the effects on teachers and teacher labor markets, there are some clear signs:

Where schools have remained open, the direct health risks to teachers do not seem to have been higher than any other occupation (for example in Sweden).

Where schools have been closed, there is an obvious and important distinction between public sector teachers, who have generally continued to receive a full salary, and private school teachers, who won’t have received anything whilst employers have been unable to charge fees.

During periods of school closure, teachers were generally not expected to report to work, though in some cases they continued to be responsible for delivering instruction remotely.

In the medium term, recessions typically lead to increases in applications for more secure public-sector jobs, raising the possibility that public-school systems may be able to select from a more competitive pool of applicants.

Read the full paper here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.