Recommended

Event

VIRTUAL

November 15, 2023 10:00—11:30 AM EDT | 3:00 - 4:30 PM GMTOn 1st October, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) entered into force in its transitional phase with reporting requirements taking effect in 2024 and full charges for 2026. Recent analyses suggest Africa’s economy will be the most affected with material impacts on many lower-income country economies, and the EU has chosen not to offer exemptions or phased implementation.

In this blog, we explore the latest developments on the CBAM, and present new analysis showing that only one of 70 low and lower-middle income countries have implemented a carbon price to date, and only a further 6 planning to do so. We identify the main options going forward, including how low- and middle-countries can develop their own carbon price and generate their own revenues; as well as the ways the EU could provide additional climate finance.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – the story so far

Proposed by the European Commission (EC) as part of the European Green Deal in 2019, the CBAM was finally adopted in May 2023, after four years of intense negotiations between the EC, the Member States and the European Parliament.

The CBAM has for main objective to place European companies, which pay for their CO2 emissions linked to their production, on an equal footing with non-EU importers. With a tax on EU-importers corresponding to the difference between the EU carbon price and the carbon price in the country of origin (if there is one), the EU hopes to avoid “carbon leakage”, as companies move their production to country with less stringent climate policies.

The levy is also crucial to mobilise resources for the EU budget in order for the latter to become less dependent on Member States’ contributions. The European Commission estimates annual revenues from the tax covering CBAM products inside and outside the EU to reach €9.1 billion by 2030. The EC is planning to use these revenues to finance the reimbursement of the borrowing of NextGenerationEU, the EU’s covid recovery package agreed in 2020.

No exemptions for developing countries

In these negotiations, low- and middle-income countries’ voices appeared to have lost two important battles. Firstly, the CBAM will not provide an exemption for least developed countries (LDCs). This contrasts with the EU’s Everything but Arms (EBA) scheme which removes tariffs and quotas for all imports of goods (except arms and ammunition) coming to the EU from LDCs. Secondly, the revenues of the CBAM will not be used to finance LDCs efforts towards de-carbonisation. Despite the European Parliament having originally adopted such position, Member States did not support the proposal and the latter was dropped in the final text.

What impact on lower income economies?

CBAM will have impacts on developing countries, in terms of reductions in trade levels and loss in GDP. A joint study between the LSE and the African Climate Foundation estimated that Africa would be the most-negatively affected of the major economies/ regions. CBAM could result in a decrease in exports from Africa to the EU in aluminium by up to 13.9%, iron and steel by 8.2%, fertiliser by 3.9% and cement by 3.1%, although some of these exports would be diverted to other destinations including China and India. GDP and income across the continent could be reduced by 0.5% (this may sound small but its four times as large as the EU GDP benefits of its Japan trade deal). Some countries (and sectors) which export high volumes of the affected products to the EU will be more impacted than others. In a previous analysis at CGD, we estimated that CBAM could lead to a 1.6% fall in Mozambique’s GDP; though the more comprehensive approach of the LSE modelling suggests this would be much lower as its exports are diverted.

The EU is already taking steps to increase the sectors covered by its own carbon market, and an expanded CBAM could have very significant trade impacts across the globe. In a scenario where all exports to the EU would be covered by CBAM and at a carbon price of €87 per tonne, African exports to the EU could be reduced by 5.72% and the region’s GDP by 1.12%. In Asia as well, such expansion could result in significant losses. If plastic products whose production is highly-carbon intensive were to be included in CBAM, Viet Nam and Thailand, two major exporters would see their GDP decrease respectively by 0.6% and 0.2%.

Will developing countries be able to implement carbon pricing in time to avoid the negative impacts?

Confronted with these impacts, low- and middle-income countries have started to think about policy responses. The EU is hoping that the CBAM will lead other countries to implement carbon pricing in the relevant industries. We have used the World Bank’s database of carbon pricing to assess whether lower income countries have successfully implemented carbon pricing.

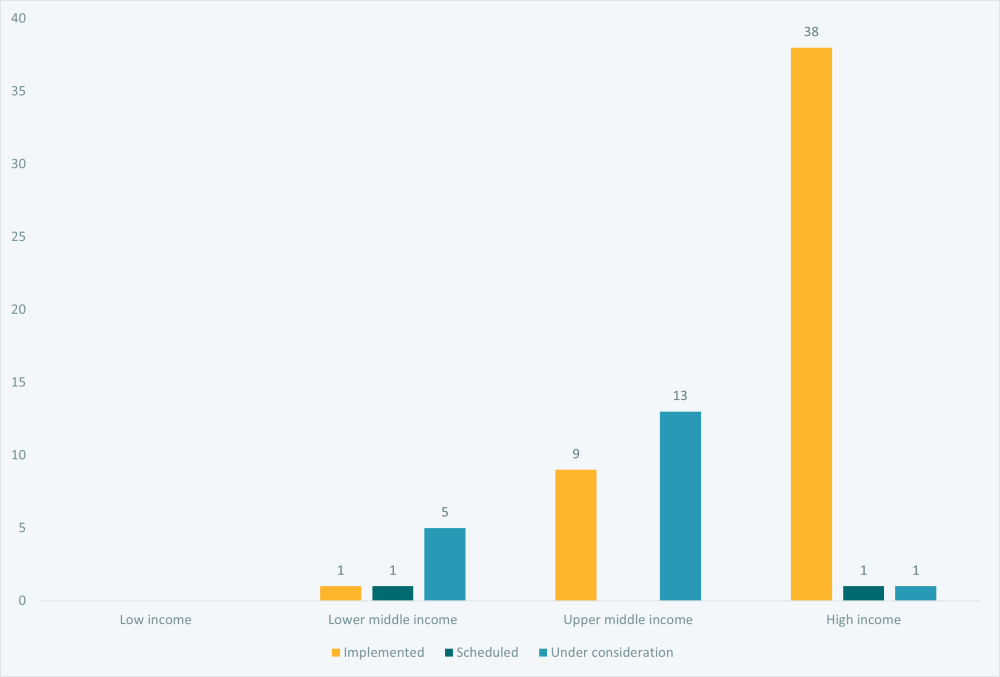

Our analysis shows that, while almost a third of high-income countries have a carbon pricing mechanism, none of the 26 low-income countries even have one under consideration. Just one lower-middle-income country (Ukraine) has implemented a carbon pricing system (2%); and only 6 such countries (11%) have one scheduled or under consideration. Even among upper-middle-income countries, the uptake of carbon pricing remains modest at 16%. Moreover, recent experiences among emerging economies in designing a carbon tax has proven difficult. In South Africa, despite being the first African country to adopt a carbon tax originally set at R120 (USD7) per ton of CO2, the effective rate of such as tax remains very low, at around R7 (USD0.4).

These figures suggest that the vast majority of lower income countries are a long way from implementing any carbon price, let alone one that targets the relevant industries. The EU committed to support the development of domestic carbon taxes in partner countries; and this analysis suggests that will present a major challenge.

Figure 1: Carbon pricing mechanism (carbon tax or emissions trading scheme) by income group

Source: CGD analysis of World Bank carbon price dashboard, accessed November 2023.

Notes: In the 2022 data, there were 26 LICs, 54 LMICS, 54 UMICs, and 83 HICs. Only regional and national schemes are including in the analysis. The EU’s ETS covers 30 countries (27 EU Member States plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) and these are included in the HIC bar. Countries are counted only once.

What other options for developing countries moving forward?

Several countries panned to challenge the measure at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) as the country estimated that it constitutes a discriminatory trade barrier. In a letter to the European Commission, the South Africa government also shared the view that it “potentially violates the provisions of the WTO on non-discrimination.

India is also considering an exports tax on products affected by the CBAM. This could be simpler than an industry-level carbon price, and the levy would be equivalent to the CBAM but collected by the Indian government as the products leave the country. According to the EU’s CBAM regulation, an exemption or a reduction of the CBAM is only possible if a “carbon price”, defined as “the monetary amount, under a carbon emissions reduction scheme, in the form of a tax, levy or fee in the form of emission allowances under a greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme, calculated on greenhouse gases covered by such a measure, and released during the production of goods” has already been paid in the country of origin. The Indian proposal appears to create sound incentives for reducing the carbon intensity of its production though it remains to be seen how the EU would view such a proposal. If the tax only applies to exports to the EU it may also fall foul of WTO rules which require equal treatment of all trading partners.

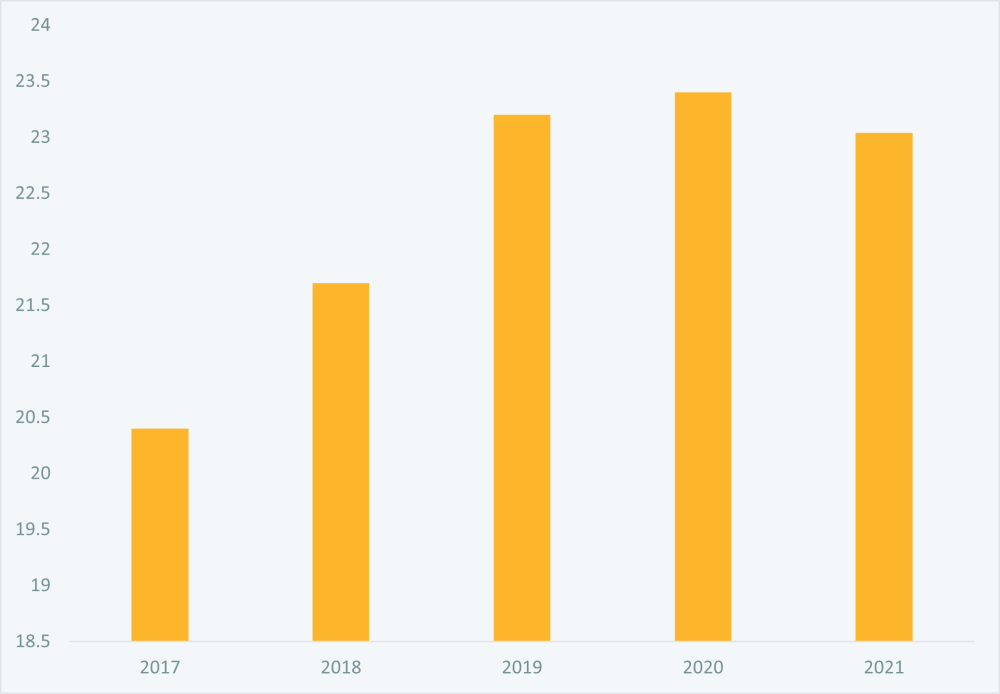

Developing countries could also put pressure on the EU to increase international climate finance towards the decarbonization of their manufacturing industries. The CBAM regulation included text which reiterated EU’s commitment to support climate mitigation and adaptation in low- and middle-income countries, albeit “within the ceiling of the EU’s multi-annual financial framework and the financial support to international climate finance”. Now the financial impact of the CBAM on developing countries will become real, the EU’s financial promises should too. With CBAM revenues estimated at EUR9.1 billion, we argue that the EU should commit to increase its climate finance, in particular for adaptation. As a matter of fact, Europe’s contribution to climate finance remained stable in 2020 and even decreased in 2021, despite pressing needs in developing countries.

Figure 2: EU’s contribution to climate finance, EUR billion, 2017-2021

Source: European Council.

Note: Figures include sources from public budgets and development financial institutions of the EU, its member states (including the UK) and the European Investment Bank.

Conclusion

The EU has taken important steps to tackle climate change with the introduction of its CBAM. Still, it has made little provision for the need for “common but differentiated responsibilities” of developing countries for its design. This may be difficult to defend with EU per head emissions at over 5 tonnes per head, relative to just 0.3 and 1.5 in low and lower-middle income countries respectively and the EU will need to offer clear and generous support to affected countries. Our analysis has highlighted the very limited carbon pricing schemes in lower income countries and suggests a substantial challenge for affected economies; and the Indian suggestion of a trade-related measure may offer a response with the right incentives but simpler to implement.

We are grateful for analysis on carbon pricing schemes by Andrea Vilaplana for this blog. All views and any errors are those of the authors.

The blog has updated on 29th November to reflect the distinction between carbon price mechanism “scheduled” and “under consideration” and to avoid double counting.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: bluedesign / Adobe Stock