As the COVID-19 pandemic reaches on past its six month mark, there continues to be a lively debate about whether it’s the virus or the response that’s having the greatest impact on people’s lives and livelihoods.

We do not seek to disentangle the damage that is caused by the virus from the damage caused by the response—the damage needs to be mitigated no matter how it is caused. Rather, we aim to provide a sense of the magnitude of the collateral heath impact in Ethiopia, where the government has implemented a range of measures to control the spread of COVID-19 but has not implemented a national lockdown like most other governments, including those in Africa.

We do not seek to disentangle the damage that is caused by the virus from the damage caused by the response—the damage needs to be mitigated no matter how it is caused.

Using our net health impact calculator and the limited publicly available data to guide the analysis, we find that Ethiopia likely faces significant excess non-COVID-19 deaths in the coming months—possibly more than the COVID-19 deaths avoided by the government’s robust response to the pandemic. We designed the calculator to help decision-makers planning the COVID-19 response in any given country to take a “whole of health” perspective that fully considers the indirect health effects of different policy responses to the outbreak.

How many COVID-19 deaths would have occurred in Ethiopia without any response?

Several models predict the number of COVID-19 deaths in Ethiopia under a variety of scenarios. Table 1 shows the predicted COVID-19 deaths in an unmitigated scenario—that is, if the government had not responded at all to the outbreak. It’s important to note that the time horizons for these models vary: the Imperial model takes the entire duration of the outbreak until a vaccine is developed (best case scenario assumed to be 12-18 months from the time of writing), the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) presents predictions for 3, 6, 9, and 12 months—and Table 1 shows the results for 12 months—and WHO AFRO takes a time horizon of 12 months. While the LSHTM predictions (200,000-490,000) are similar to those from Imperial (281,678), there is a 100-fold difference between these estimates and those from WHO’s Regional Office for Africa (WHO AFRO).

By way of comparison, the Global Burden of Disease project estimates that there were around 540,000 deaths in Ethiopia due to all causes in 2017 (most recent year available). This means that, if no action took place to mitigate COVID-19 deaths in Ethiopia, COVID-19 deaths would have represented as many as 52 percent, or 37-91 percent of all deaths, according to the Imperial or LSHTM models respectively. Or “just” 0.5 percent if one believes the WHO AFRO predictions.

Table 1. Predicted COVID-19 deaths in Ethiopia over 12-18 months in an unmitigated scenario

| Model | Imperial | LSHTM (95% interval) | WHO AFRO (failed containment scenario) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 281,678 | 200,000-490,000 | 2,713 |

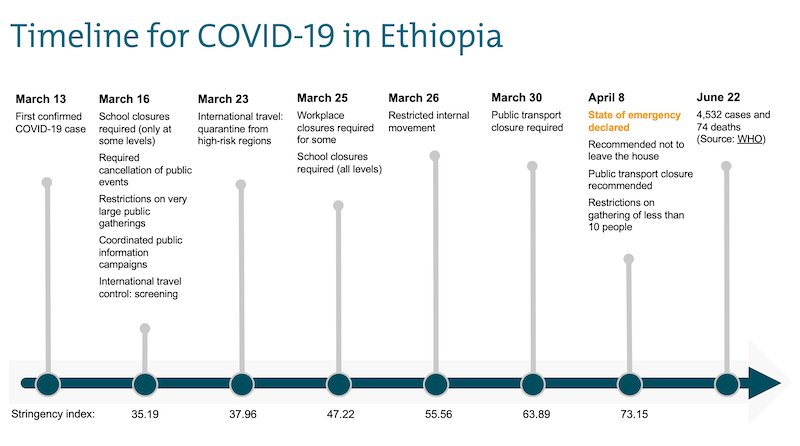

Since 13 March, when Ethiopia confirmed its first case of COVID-19, there have been roughly 4,532 confirmed cases and 74 deaths. This relatively “low” death toll could be attributed to the introduction of measures from the government.

Ethiopia’s response

The Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker project calculates a Government Stringency Index, a composite measure of nine response metrics: school closures, workplace closures, cancellation of public events, restrictions on public gatherings, closures of public transport, stay-at-home requirements, public information campaigns, restrictions on internal movements, and international travel controls. In Figure 1, we show the timeline from the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Ethiopia, along with the dates of the nine key metrics (including changes for some of them over time). As of 8 April 2020 until June 22, Ethiopia’s stringency response is 73.15 out of 100.

Figure 1. Timeline of Ethiopia’s COVID-19 responses

Non-COVID-19 deaths

We use the most recent (2017 estimates published in 2019) Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates to model potential excess deaths due to disruption in services from COVID-19. As noted above, we do not seek to explain what’s causing these deaths: fear of the virus or the measures implemented to suppress it.

In Table 2 we present predictions of deaths from the indirect health effects of COVID-19 and the policy responses in three categories: communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases; noncommunicable diseases; and injuries. The table shows assumptions in terms of the intensity (how much disruption is caused), and duration (how long the disruption lasts). We assume the disruptions will be felt for the duration of the outbreak; conservatively, we assume this to be 18 months as defined by Imperial’s model.

Communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases

Using the Lives Saved Tool, Johns Hopkins University reported that across 118 low- and middle-income countries, the increase in child and maternal deaths will be devasting. Based on a range of plausible scenarios, the authors estimate that in Ethiopia there could be as many as 57,000 additional child deaths and 2,300 additional maternal deaths in this first year of the pandemic as a result of unavoidable shocks, health system collapse, or intentional choices made in responding to the pandemic (equivalent to 86,000 excess child and 3,500 excess maternal deaths over 18 months).

While the GBD causes of death and child and maternal categories are not perfectly aligned (GBD includes a category for maternal and neonatal disorders but child mortality is spread across multiple causes), we nevertheless used the Johns Hopkins estimates to “anchor” the calculator and assume that there could be a 30 percent increase in all deaths due tocommunicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases,gradually decreasing to a 10 percent increase over 18 months (note, other combinations of increases in mortality over time would lead to the same results).

If we believe the Hopkins estimates are plausible, and we use their third scenario where, in addition to disruptions in the health system, they assume that governments recommend or impose strict movement restrictions, leading to families and non-essential workers staying home (which matches the policies the Ethiopian government has introduced), our disruption and duration assumptions probably underestimate the potential indirect health impact. Our assumptions, across all seven categories of communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases (see Table 2) lead to 89,546 excess deaths compared to the 89,500 excess child and maternal deaths estimated by Hopkins. Hopkins did not consider excess adolescent or adult deaths (beyond maternal deaths). And by “fitting” our estimates to the Hopkins numbers, we therefore underestimate the toll of excess deaths across all age groups for this broad category of deaths.

Non-communicable diseases

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) account for an increasingly large proportion of deaths globally. In Ethiopia, NCDs accounted for 37 percent of deaths in the 2017 GBD. However, unlike communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases, for which interventions are relatively well-established (and where we have pretty good coverage data), the coverage of control measures for NCDs (e.g., hypertension screening and treatment, diabetes diagnosis and care, cancer diagnosis and treatment) is low, more available to the wealthy, concentrated in urban populations, and poorly tracked.

If COVID-19 disrupts routine health services and leads to excess mortality, that disruption will be felt more acutely where there's something to disrupt. Ethiopia’s recent NCD and injuries commission reported average effective coverage for NCD services to be below 10 percent. Therefore, we conservatively assume that there will be a 5 percent increase in all deaths due to NCDs, gradually decreasing to a 1 percent increase over 18 months.

Injuries

For the injury category of cause of death, we assume that the duration will be limited to the period of stay-at-home recommendations (introduced on 8 April 2020), and we assume these will last for three months. We also assume that mobility restrictions during the pandemic will lead to fewer deaths from road accidents. Both of these causes of deaths are assumed to go down by 50 percent, gradually returning to pre-COVID-19 levels after three months. Similarly, we assume the stay-at-home recommendations will lead to fewer deaths from occupational injuries. Sadly, reports of self-harm and interpersonal violence have gone up, including in Ethiopia. Deaths due to these causes are assumed to go up by 20 percent, gradually returning to pre-COVID-19 level after three months.

We believe excess non-COVID deaths in Ethiopia will be significant, ranging between 25,000 to 97,000 additional deaths over 18 months.

Based on our assumptions, we find that there could be as many as 97,000 excess non-COVID-19 deaths over the next 18 months; more than 90 percent of these deaths would be due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases.

Table 2. Indirect health effects due to COVID-19 and the policy responses

| By cause of mortality | GBD deaths (2017) | Impact (%) - start value | Impact (%) - end value | Duration | Indirect effects – “worst case” scenario | Indirect effects – “least bad case” scenario (see text for assumptions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases | 298,486 | 30% | 10% | 18 months | 89,546 | 22,386 |

| Non-communicable diseases | 196,669 | 5% | 1% | 18 months | 8,850 | 3,688 |

| Injuries | ||||||

| Transport injuries | 10,266 | -50% | 0% | 3 months | -642 | -642 |

| Unintentional injuries | 18,084 | -50% | 0% | 3 months | -1,130 | -1,130 |

| Self-harm and interpersonal violence | 13,484 | 20% | 0% | 3 months | 337 | 337 |

| Excess in indirect health effects | 98,733 | 26,411 | ||||

| Reduction in indirect health effects | -1,772 | -1,772 | ||||

| Net indirect health effects | 96,961 | 24,639 |

A “least bad case” scenario of non-COVID-19 deaths

Recognizing that there is much uncertainty about these estimates, we also consider a “better-case” scenario (because there is no good or best-case scenario).

Here, again, we use the recent estimates from Hopkins (their scenario 1), who reported 20,000 additional child and 850 additional maternal deaths over 18 months to “anchor” our estimates. Crudely speaking, this is equivalent to a 10 percent increase in mortality due to communicable, maternal, neonatal, and nutritional diseases, gradually returning to pre-COVID-19 levels over 18 months (again, other combinations will lead to the same outcomes). For NCDs, we lower our assumptions to a 2.5 percent increase gradually reducing to pre-COVID-19 levels over 18 months. We maintain the assumptions for injury causes of mortality. This “least bad case” scenario results in 25,000 excess non-COVID-19 deaths (see Table 2).

We must assess what works best in terms of mitigating this damage, e.g. how are health systems, programs and providers adapting and innovating to get services up and running again.

Conclusions

- The government of Ethiopia responded robustly to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we do not know the effectiveness of specific policy responses and how they work together. Nor do we know enough today about how effectively responses in Ethiopia (or elsewhere) were enforced. For example, public transportation was never closed in Ethiopia despite the measure being recommended on April 8.

- Unlike most other countries, Ethiopia chose to not implement a national lockdown. It remains to be seen whether this will lead to more, or fewer, COVID-19 deaths.

- Similarly, it remains to be seen whether the absence of a lockdown reduced the indirect impacts to the population health. Indeed, it is unclear whether these avoidable non-COVID-19 deaths will be entirely due to lockdowns and other policy measures. Healthcare avoidance due to fear of the virus will contribute to these deaths. More work will be required to disentangle the damage that is caused by the virus from the damage caused by the response.

- Nevertheless, despite what appears to be robust response to control the spread of COVID-19, we believe excess non-COVID deaths in Ethiopia will be significant, ranging between 25,000 to 97,000 additional deaths over 18 months.

- These excess non-COVID-19 deaths may be greater than the COVID-19 deaths avoided by the actions taken by the government of Ethiopia.

- Every country will be seeking to mitigate the indirect health damage inflicted on its people through a combination of the virus and measures taken to control the virus. It will be important to assess what works best in terms of mitigating this damage: how are health systems, programs, and providers adapting and innovating to get services up and running again?

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.