UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres has said gender equality at the United Nations is “an urgent need – and a personal priority. It is a moral duty and an operational necessity.” Guterres was quick to meet his goal of gender parity in UN senior management. But 18 years past an initial 2000 target date for gender parity in the UN system as a whole, there is still a long way to go. The organization remains off track to meet the new target for parity at all levels by 2030. There is also evidence that the rate of change will be hard to boost without a new approach.

The latest Secretary General’s report on the improvement in the status of women in the United Nations system finds representation of women in the professional and higher categories in the United Nations system increased from 41.6 to 42.8 percent between 2015 and 2017, but accepts women are still concentrated at lower levels of the organization, culminating in a low of 26.8 percent at the highest level.

UN Women predicts when gender parity will be achieved at various levels of staff and management given trends between 2005 and 2015. Professional staff levels go from P-1 (the most junior) to P-7 (the most senior) but nearly all professional staff are in grades P-1 through P-5 (the highest). Above that are two director grades (D-1 and D-2), then under-secretary general. For the UN as a whole, current trends suggest P-5 parity will occur in 2034 and Under Secretary parity in 2054. For the UN Secretariat the dates are between 2050 and 2054 for P-4 and P-5 staff, never for D-1 and 2062 for D-2 management. For the UPU, parity for D-1 positions might occur by 2099 on current trends and for D-2 and Under-Secretary positions parity will never happen. For an international organization that has committed to total global gender equality as part of the Sustainable Development Goals, this rate of improvement needs a bit of a boost.

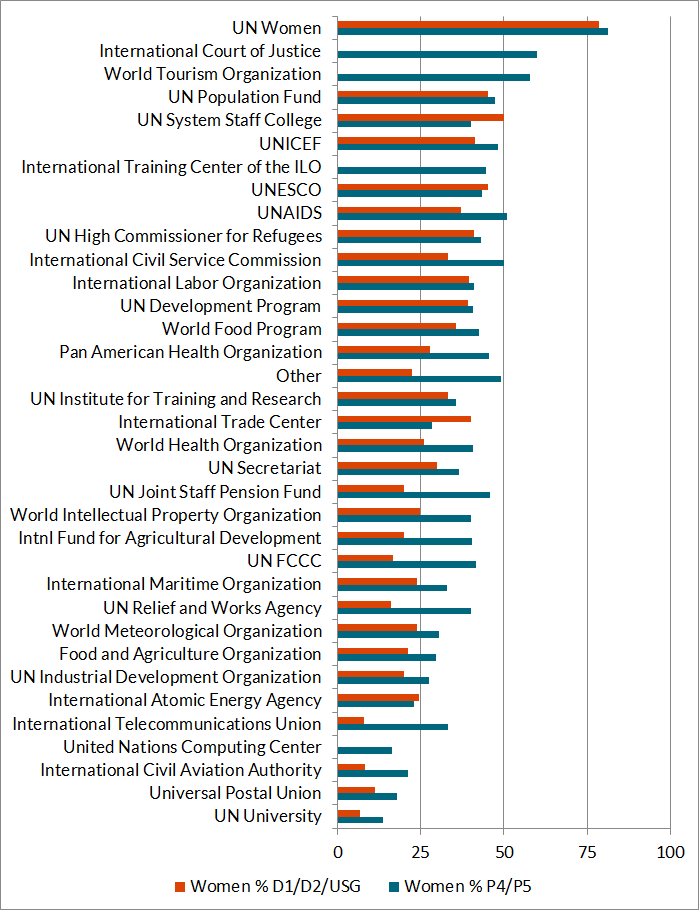

The latest publicly available database covering the gender breakdown of UN staff only covers 2015. But using the data available there, we put together information on staffing by gender, grade level, length of service and agency (See Figure 1). Little surprise that the agency with the most women in senior roles is UN Women. But no other UN agency with data sees gender parity at the D-1/D-2/USG level. Fourteen agencies—including the International Civil Aviation Authority, the ITU, and the UN FCCC—see less than 25 percent representation at the director and under-secretary general level. Things are only marginally better amongst senior staff. Despite the United Nations University’s commitment to implementing the UN’s policy on gender mainstreaming, only 14 percent of P-4 and P-5 staff are women. Only 10 of 35 agencies with data see women represent more than 45 percent of senior professional staff.

Figure 1. Proportion of Senior Staff/Management Who Are Women in UN Agencies

The Secretary General’s report points to a number of barriers to progress: career advancements were at or near gender parity at the P-1 to P-4 levels but not above that (women account for only one third of Director advancements). Men and women are leaving the organization at the same rate, but the men are more likely to leave because of retirement while women are more likely to leave earlier because of appointment expiration or resignation. And at every grade level, women comprised less than half of all external applicants to the United Nations system.

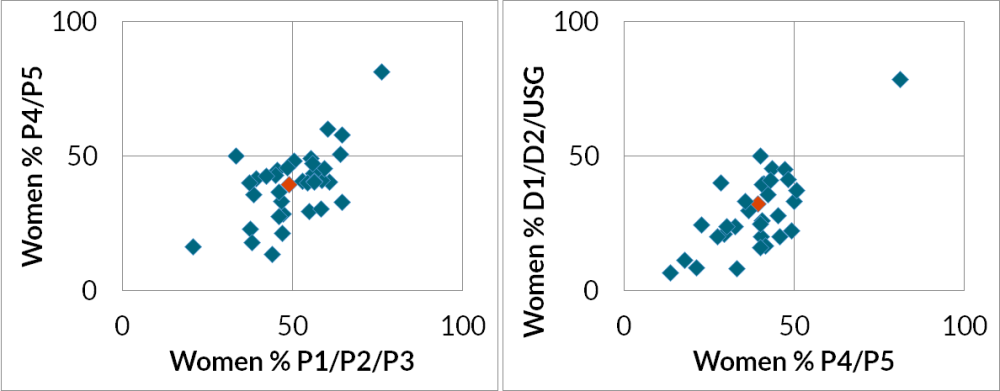

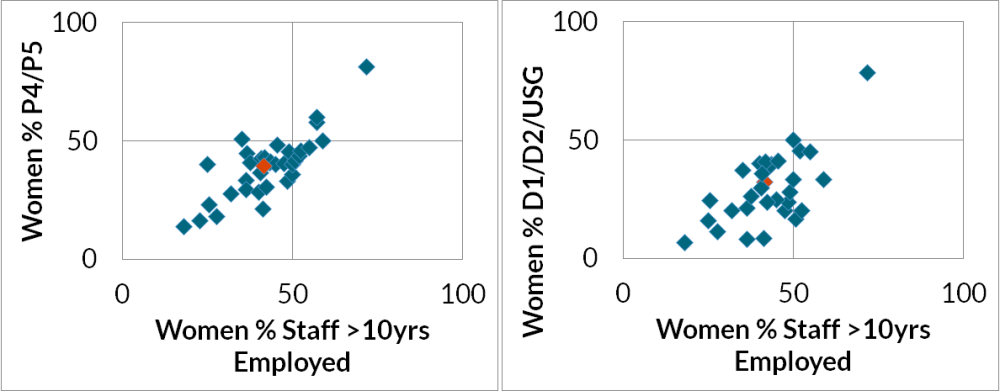

The data also suggests that it might be hard to rapidly improve the performance of laggard institutions on the traditionally dominant model of promoting from within. Across agencies, there is a strong correlation between the percentage of junior professional staff who are women and the proportion of senior staff and directors who are women (Figure 2, the red datapoint is the UN average). Again, agencies where women are a higher percentage of staff with 10-year plus tenures also see more senior women (Figure 3). That points to the importance of building up a pipeline of junior professional women who can later occupy senior posts –a process that takes time and appears nascent in some agencies.

“Policies abound, but effective implementation holds the key” to gender equality by 2030, the Secretary General’s report suggests. But laggards like the United Nations University and the ITU might need more policy along with better implementation if they are to make rapid progress in the next few years—not least far greater efforts to reach both in and outside the UN family to fill senior spots with qualified women candidates as well as more active encouragement for internal candidates.

Figure 2. Organizations with More Senior Women Have More Junior Women

Figure 3. More Long-Tenure Women = More Senior Women

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.