Recommended

Blog Post

Blog Post

With several replenishment campaigns set for 2024-2025, a fundraising pileup is on the horizon. Close to a dozen major development funds—including the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), thematic funds like Gavi, and new entities like the Loss and Damage Fund—could aim to raise over $100 billion from donors over the next two years, according to our projections.

This isn’t the first replenishment “traffic jam” because most funds are on three- or five-year fundraising cycles. The last one, in 2019-2020, had a relatively successful outcome with 6 funds raising close to $60 billion. But today’s landscape is vastly different. Foreign assistance budgets across key donors are increasingly constrained by domestic fiscal tightening and new claims on resources in a challenging geopolitical landscape. Upcoming elections in 6 of the 10 largest bilateral donors also introduce an element of political uncertainty. Given that the same donors tend to dominate these funds, there is a risk that 2024-2025 could become a zero-sum competition for a fixed pot of resources.

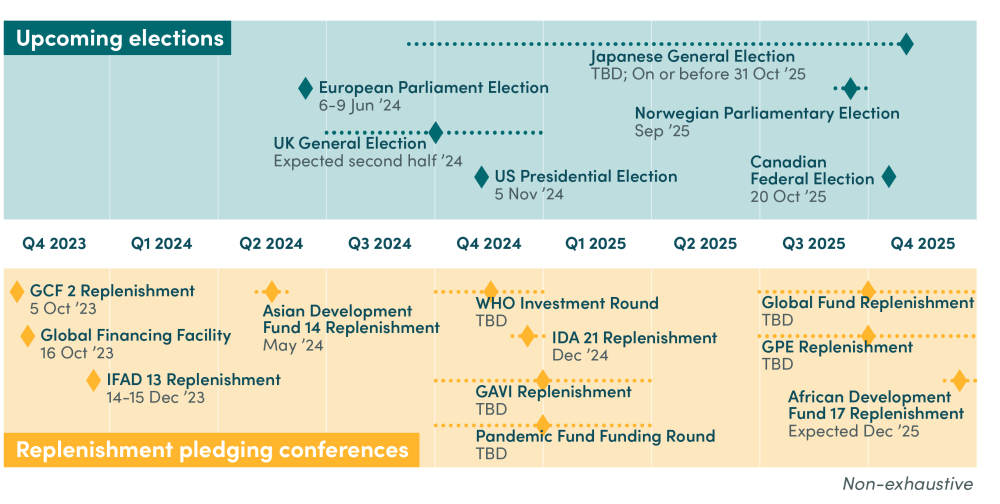

Below, we map key replenishments in 2024-2025 (see Figure 1), outline three reasons why this upcoming period could be particularly challenging, and share what we will be watching over the coming year.

Figure 1. Snapshot of upcoming replenishments and elections in major donor countries in 2024-2025

Notes: This timeline is non-exhaustive. Elections depicted here are only for the 10 largest bilateral donors; timings for replenishment pledging conferences are authors’ best estimates based on latest information available.

Why the situation is more concerning this time around

Replenishment “traffic jams” aren’t new; there was also one in 2019-2020, as discussed and described by former CGD colleagues Scott Morris and Amanda Glassman. But we believe prospects are gloomier this time around for the following reasons:

1. Replenishments are ‘big money’, but it’s unclear if there’s enough cash to go around

Foreign aid budgets are under pressure amidst global economic headwinds, with growth projected to slow for a third year, the prolonged war in Ukraine, and conflict in the Middle East. The latest OECD DAC figures show that many donors are counting the costs of hosting refugees within their own borders as aid, and rather than allocating additional funding for support to Ukraine, they are shifting resources away from other development priorities.

Our back-of-the-envelope estimate suggests that ambitions for the upcoming fundraising efforts over the next two years could exceed $100 billion. Perhaps most notably, World Bank President Ajay Banga has already signaled he wants the IDA replenishment to be the “largest of all time,” and is targeting $30 billion in donor contributions. (Donor pledges to IDA have declined over the past decade. The last replenishment, in 2022, reached a record $93 billion, though largely due to internal resource mobilization rather than increased contributions, which stood at $23.5 billion.)

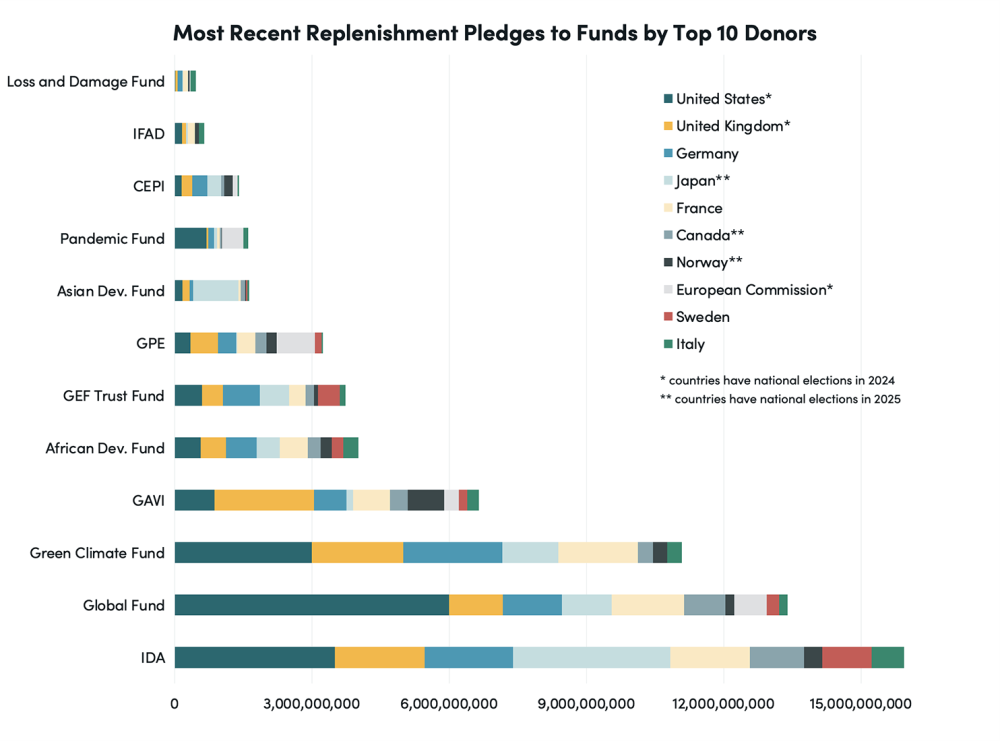

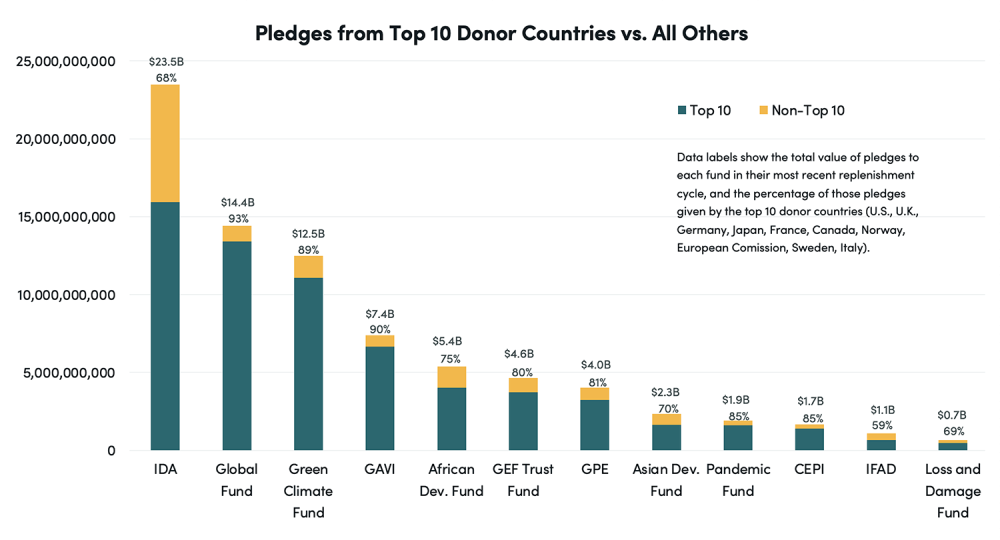

Looking at the largest funds, the same 10 donors tend to dominate across replenishments (Figure 2; see also Figure 6 here for historical trends). And in the prevailing environment, existing donors appear unlikely to bring significant additional resources to the table.

Figure 2. Most recent replenishment pledges to funds by top 10 bilateral donors

Notes: All values represent pledges. Figures for Gavi exclude pledges for the COVAX AMC.

2. New funds mean more competition

Since 2019, we have seen the introduction of new funds: the Loss and Damage Fund, launched in 2023 to compensate countries for climate-related shocks, has received roughly $700 million in donations to date; and the Pandemic Fund, launched in 2022 to channel additional, dedicated financing for pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response has raised $2 billion.

Further, as part of a revamped financing model, the World Health Organization is planning to host an “investment round” in late 2024 to raise $7.1 billion for its core budget for 2025-2028 (Figure 1).

All will rely on the same set of donors to deliver. For example, the Pandemic Fund’s largest contributors—among them the EU, US, and Germany—are also the top funders across global health, pointing to competing priorities within sectors, as well as outside them (think climate). The largest pledges to the Loss and Damage Fund have come from Germany, France, and Italy—albeit alongside the United Arab Emirates, a historically small multilateral donor—with fundraising efforts expected to continue throughout the year.

In addition, the World Bank and key shareholders are seeking to shore up funding for its Global Public Goods Fund, which CGD colleagues previously estimated could require around $10 billion in resources. To date, the US is the only country to have made a significant pledge ($1.25 billion), but it’s not at all clear the US Congress will approve the funding needed to deliver. And unlike other funds described here, the World Bank GPG Fund is largely intended for middle-income countries—setting up a direct financing trade-off with IDA and other funds that primarily serve the poorest countries.

Figure 3. Most recent replenishment pledges to funds by top 10 bilateral donors vs. all others

Notes: All values represent pledges. Figures for Gavi exclude pledges for the COVAX AMC.

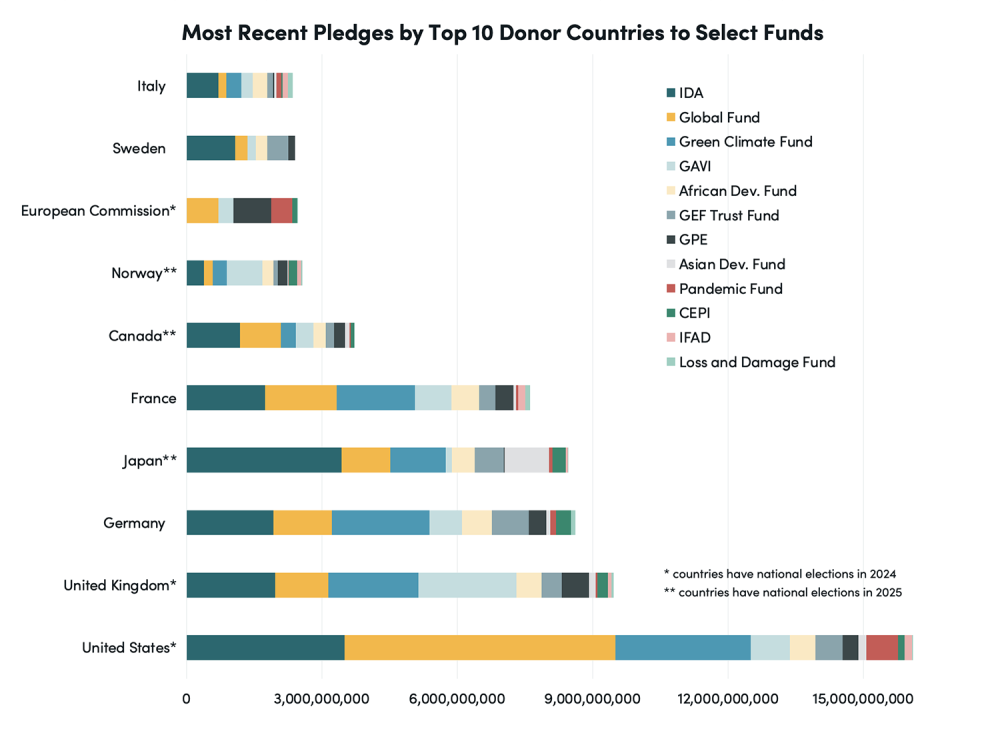

3. Upcoming elections in many major donor countries could add more uncertainty to pledges

2024 is also being hailed as the “biggest election year in history.” Six of the ten largest bilateral donors have upcoming elections this year or next, fostering unpredictability and uncertainty for fundraisers (Figure 4). While the exact timing is still being firmed up, the last quarter of 2024 could see multiple pledging conferences and fundraising efforts, including IDA21, Gavi, and the Pandemic Fund, as well as WHO’s “investment round.” This period will also coincide with the next UK general election and the US presidential election (see Figure 1). To compound matters, some European countries, including Germany and Switzerland, are facing domestic budget crises that could result in ODA cuts.

Figure 4. Most recent pledges by top 10 bilateral donors to select funds

Notes: All values represent pledges. Figures for Gavi exclude pledges for the COVAX AMC.

What we’re watching

1. New and emerging donors

A key question is whether new funders will fill space that may be ceded by traditional donors. China’s growth as a major donor to IDA has been notable, having risen to sixth largest in IDA20 from number 20 two decades ago. However, the pace of China’s growth as a multilateral donor has slowed in recent years.

Other key players worth watching include the Gulf donors. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have historically been unreliable donors but, in recent years, have been trying to reassert their presence in multilateral institutions. Saudi Arabia is reportedly hoping to host the IDA replenishment pledging session this December, presumably signaling a willingness to grow its financing footprint. (Saudi Arabia has increased its IDA contribution sixfold over the last three replenishment cycles, but started from a relatively low base.) Another rising donor is South Korea, which is significantly expanding its overseas spending and may see multilateral funds as an effective steward for its overseas spending.

Finally, there’s also a question about whether philanthropies will step up their contributions to the thematic funds, especially the global health initiatives; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, just announced an $8.6 billion annual budget for 2024, its largest to date.

2. Election outcomes

The outcome of elections in major donor countries could also have big implications for fundraising ambitions. The billion-pound gorilla is the United States. The US election in November is shaping up to be a contest between two candidates with different visions for multilateral engagement and foreign aid. The Biden administration has embraced an expansionist approach to multilateral foreign assistance, urging Congress to provide boosts in funding for several multilateral organizations (though lawmakers haven’t always gotten on board). While in office, former President Donald Trump—the current GOP frontrunner—generally took a more skeptical view of multilateral cooperation and sought deep cuts in foreign aid (though, again, Congress didn’t necessarily deliver).

And although it looks unlikely that new leadership in the UK will seek to restore the commitments to provide 0.7 percent of their budget as ODA, that doesn’t foreclose on the possibility of a new government upping its IDA contribution.

Beyond elections, how countries like Germany navigate domestic budgetary crunches and what spending they choose to protect will also be critical.

3. Verticals versus core development

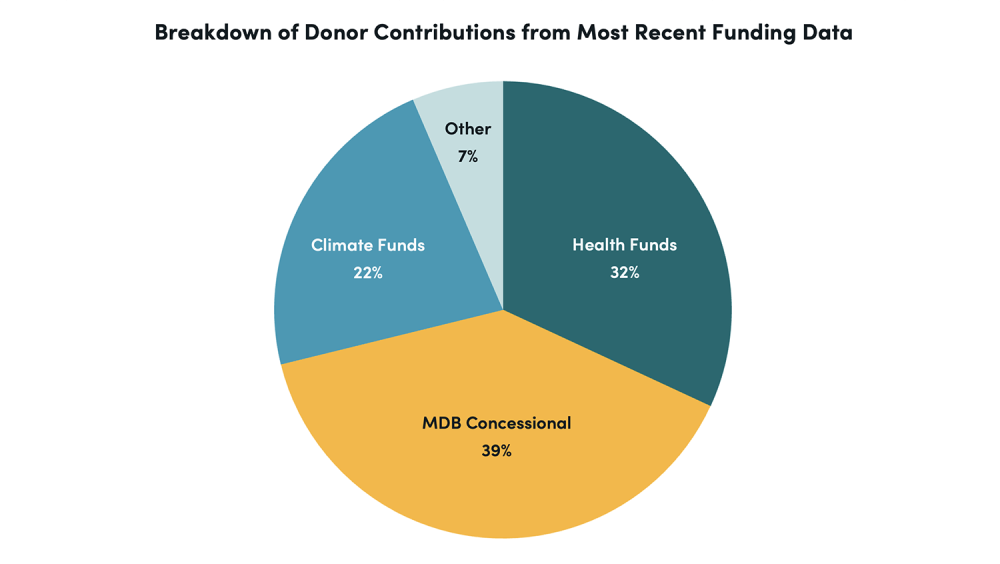

The rise of the specialized vertical thematic funds is a prominent feature of today’s concessional financing landscape (Figure 5). Most multilateral grant funding supports vertical funds (i.e., those earmarked for a specific purpose such as health, food security, or climate). In contrast, MDB concessional funds like IDA, the Asian Development Fund, or the African Development Fund, give recipient countries access to development funding that they can invest according to their national priorities. (There has also been a recent push for the global health funds to increasingly leverage the MDBs by “pooling” or “blending” financing.)

While recipient countries may prefer the flexibility of core MDB financing, vertical thematic funds may be easier to explain to donors’ domestic constituencies. Regardless, contributions to vertical funds have trended upward, while overall contributions to IDA have decreased. In contrast, new emerging donors like China seem to favor traditional development funds like IDA while largely shunning the vertical thematic funds. With many low-income countries facing severe exogenous shocks that put their development trajectories at risk, there is a case to be made that traditional donors should grow their financing envelopes to the MDB concessional funds. But political feasibility could be a real question.

Figure 5. Breakdown of donor contributions (most recent funding data)

--

The results of this next wave of replenishments will help define the global health, climate finance, and development landscape for years to come. We’ll be keeping a close eye on them over the coming months. Watch this space!

Thanks to Rachael Calleja, Erin Collinson, Javier Guzman, Anita Kappeli, Karen Mathiasen, and Ian Mitchell for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Dilok / Adobe Stock