Temporary Work Visas: A Four-Way Win for the Middle Class, Low-Skill Workers, Border Security, and Migrants

April 2013

Summary

The US economy needs low-skill workers now more than ever, and that requires a legal channel for the large-scale, employment-based entry of low-skill workers. The alternative is what the country has now: a giant black market in unauthorized labor that hinders job creation and harms border security. A legal time-bound labor-access program could benefit the American middle class and low-skill workers, improve US border security, and create opportunities for foreign workers.

Low-skill workers from abroad have built the US economy, while seizing opportunity for themselves and their families, since before 1776. Their work grew the US economy and created most of the middle-class and low-skill jobs that exist today.

This has not changed. To continue creating jobs, the economy needs new low-skill workers now more than ever, and that requires a legal channel for the large-scale, employment-based entry of low-skill workers. The lack of such a channel results in a giant black market in unauthorized labor that hobbles US job creation, while directly undermining US border security.

There is a better way—a policy win for everyone involved. Everyone. A well-designed temporary work visa program (also referred to as “guest worker program”) could create well-regulated opportunities for foreign workers to fill low-skill positions in the US. Designed correctly, a temporary visa program can be good for the US middle class, good for US low-skill workers, good for border security, and good for foreign workers.

Temporary Workers Create Good Jobs for the American Middle Class

Major reforms to the US immigration system happen rarely (the last was in 1986), so policymakers must consider the economy’s employment needs not just now, but 10 and 20 years from now. While unemployment is currently high, most economists agree this is due to weak macroeconomic recovery from the 2008 crisis. The workers filling new jobs in the coming decade will be the workers who propel the recovery. What jobs will these be, and who can fill them?

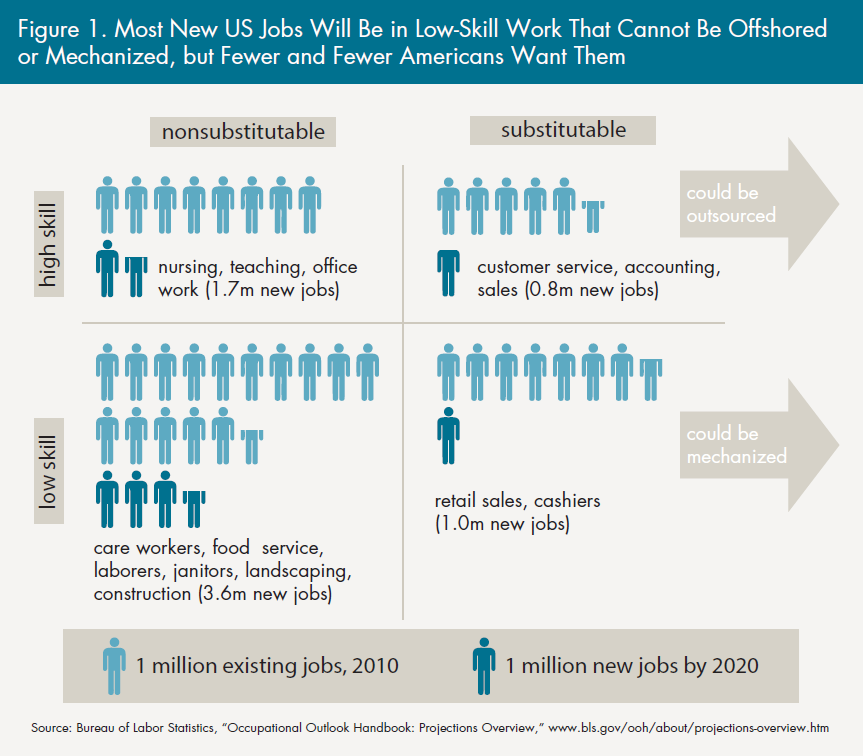

We start from the standard projections by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on the current level and expected growth in jobs by occupation. We use a method Lant Pritchett first employed in his 2006 book Let Their People Come to divide the service sector in two ways. The first division is between high skill and low skill. The second division is between substitutable jobs that can be lost to offshoring or to machines and what we call hard-core nonsubstitutable service jobs (see figure 1). These jobs require face-to-face contact and nonroutine actions.

High-skill nonsubstitutable jobs

Start with the jobs that are high-skill and hard-core nonsubstitutable: nurses, teachers, policemen, university professors. These are good jobs that Americans want. The BLS projects a gain of 1.7 million jobs like these over the coming decade. The good news is that there will be enough such jobs for every new American worker to be added to the labor force over the next decade. As Mitra Toossi of the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects in the January 2012 edition of the Monthly Labor Review, there will be about 1.7 million new American workers aged 25 to 54 in the coming decade.

Low-skill nonsubstitutable jobs

Now consider the jobs that are low-skill and hard-core nonsubstitutable: home health aides, nursing aides, food service workers, janitors. The BLS projects that the US economy will need an additional 3.6 million people to work in these jobs. This figure does not include the additional 1.8 million jobs in the substitutable sectors, such as retail sales and customer service.

Who is going to fill those jobs? They are not typically the jobs American want as the basis of their long-term career prospects. In many sectors, employers—including individual families—find a shortage of available workers. And without workers, these sectors cannot grow or generate all the other jobs they create.

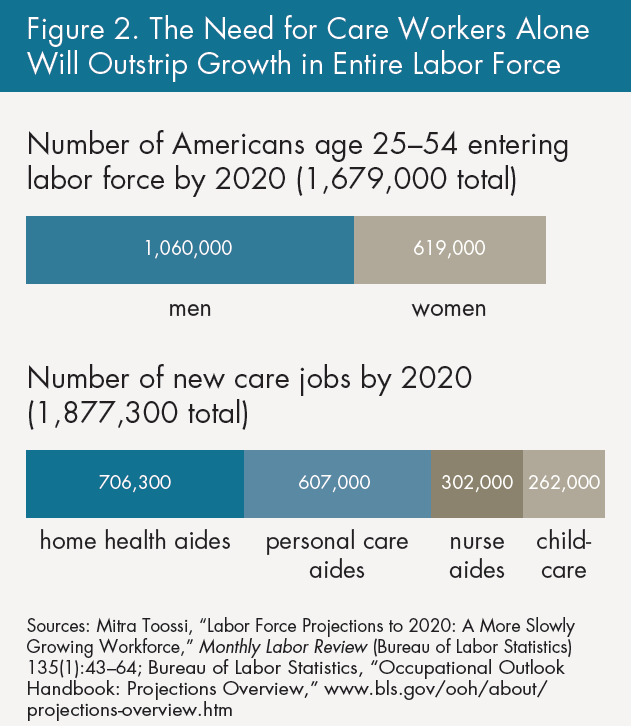

For example, take just the low-skill jobs in the care industry—not doctors and nurses, but home health-care aides, nurses’ aides, personal-care aides, and child-care providers. The BLS projects there will be more jobs added in just those four occupations (1.9 million) than the total increase in the 25–54 labor force of 1.7 million (see figure 2).

The American middle class is going to thrive by upgrading the skills of the labor force to take high-skill positions such as nurses, doctors, and teachers. Those jobs can exist only with complementary low-skill jobs in the same, nonsubstitutable sectors: nurse practitioners require health aides, teachers require janitors. But as the so-called sandwich generation—those who care for elderly parents and for their own children—grows and the baby-boomers age there will be an increasing need for care workers to keep high-skill Americans in the labor force. That is the need that a well-designed program for temporary workers can meet.

Temporary Workers Create Low-Skill Jobs for Americans Too—More Jobs, Better Jobs

A well-designed time-bound labor-access program also creates more opportunity for low-skill American workers by sustaining the sectors that employ them. This might seem counterintuitive as many people think and talk about jobs as if they were sandwiches—if he eats it I don’t, and when it’s eaten it’s gone. But the effect of an additional worker on the number of jobs in any economy depends on the balance between what economists call displacement effects (Did a foreign worker take a job a native would have taken?) and multiplier effects (Did the foreign worker create other jobs for natives?).

Economists have studied this balance for decades, and there is a rock-solid consensus among all serious researchers that existing migration (both authorized and unauthorized workers) has almost exactly offsetting displacement and multiplier effects on the US economy. No matter how economists slice the data, they find the net impact of existing migration flows on wages and employment of average Americans is close to zero.

Economists differ only in the question of whether many decades of mostly permanent immigration, authorized or not, have caused a few percentage points’ difference up or down in the wages of average US workers. These few percentage points are negligible compared to other forces that have shaped US workers’ real wages over recent decades—technological change, economic crises, college education, real-estate markets, international trade, and others. This bears repeating: not one leading labor economist finds that the cumulative immigration of authorized and unauthorized workers over recent decades—and it has been substantial—has been a quantitatively important determinant of average US workers’ wages.

How can economists conclusively show that a much greater supply of labor has only tiny effects or no average effect on US workers’ wages? Doesn’t simple logic suggest that if there is more of something, its price must go down? The reason is the multiplier effects: new workers have a positive effect on the economy and, hence, on the demand for labor, leading to more jobs for everyone.

The multiplier effects happen in four ways:

- Migrants spend some part of their income in America and stimulate additional demand here. Migrants are sellers of their own labor; they are also consumers of the produce of other workers’ labor.

- Firms and farms that employ foreign workers keep entire industries alive, and those industries employ many US workers. For example, large portions of US agriculture—apples, cucumbers, sweet potatoes, lettuce, melons, and many other crops—would cease to exist without labor for fieldwork. That means that fieldworkers expand the whole US economy by the value of those industries, and that creates US jobs in all sectors. Often the real option for American industry is not foreign workers versus American workers, but foreign workers versus having no industry at all.

- Foreign workers often do not displace other workers in the labor force but rather “home” work or chores—often performed by women—that displace time that could be spent in employment. Estimates from around the world suggest that access to care workers and, more generally, home workers increases participation in the labor force and hours of more highly skilled native workers. Having help at home allows women to “lean in” to their careers.

- Having foreign workers in low-skill jobs sustains the need for management positions, creating good jobs that Americans want. Many low-skill workers are being displaced by machines (for retail check-out, airline check-in, automated pay for parking, and so on), along with the first-line managers who supervise them. Having more low-skill workers in low-skill jobs creates more career-path management jobs (front-line and middle) in a way that machines do not.

The same multipliers take hold in temporary visa programs. And careful design can make them even larger: a good program can direct workers to industries that would otherwise attract few Americans. Even the chaotic, largely black-market way that these jobs have been filled in recent years has led to multiplier effects that completely or almost completely offset the displacement effects. Larger multipliers under a well-regulated program can more than offset displacement effects—with positive net impacts on American jobs and wages.

Temporary Worker Programs Help to Secure American Borders

The choice is not between having foreign workers fill jobs and not having them fill jobs. The choice is between laws that fuel US economic growth and job creation and laws that starve the US economy, while creating vast and potentially dangerous black markets for the labor the economy needs.

The country has been at this crossroads before, and it took a wrong turn. The last major immigration reform, in 1986, failed to create new channels for authorized temporary labor. Lawmakers thought it would be enough to regularize many of the 3 million unauthorized workers then in the country and step up border enforcement.

What happened was clear—and dramatic. The US economy continued to need low-skill foreign workers to grow, and within a few years all the regularized workers were replaced with new unauthorized workers. A few years after that, there were many more—and eventually 9 million more—unauthorized workers than before the regularization that myopically and spectacularly failed to solve the problem (see figure 3).

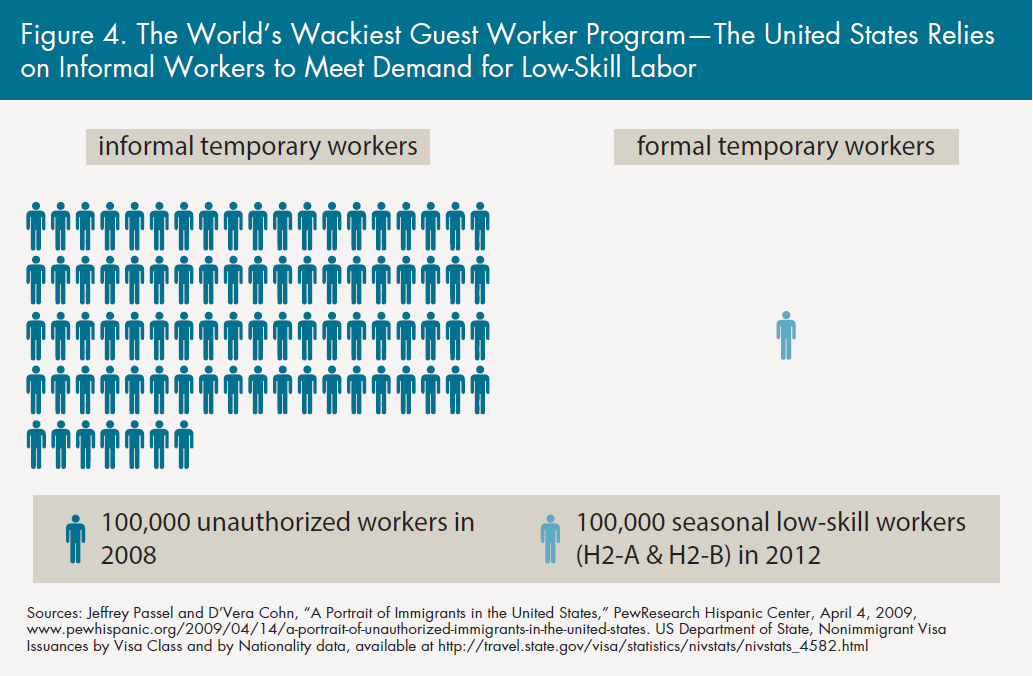

It is often argued that a “guest worker” program is politically unacceptable, but that is not quite right. Many prosperous countries—such as New Zealand, Singapore, and Kuwait—operate large-scale formal programs for temporary workers. But America’s is by far the world’s largest—and wackiest—guest-worker scheme. The United States has far more low-skill foreign workers than Singapore or Kuwait but forces its employers to rely on the black market (see figure 4).

Acknowledging that not everyone who is allowed to work in the United States is automatically on a path to citizenship is part of the political difficultly. Giving all migrants the chance to eventually become legal permanent residents or citizens would be ideal, and one compromise would be to give some low-skill temporary migrants an opportunity to adjust their status and become permanent residents. But, whether opportunities for adjustment of status are available or not, the real alternative to a formal program for low-skill workers is a labor shortage or a black market.

So far, the United States has simply eliminated most legal options for the economy to get the low-skill labor it needs and has thereby created a black-market guest-work “program.” This does not reduce the number of workers. It simply pushes guest work out of the scope of regulatory enforcement, leaving foreign workers at risk of abuse and exploitation, American workers without protection, employers without legal recourse, and Americans divided about border security. One cannot secure the border exclusively at the border; security requires enforcement, but enforcement requires meeting legitimate needs in legitimate ways.

The experiences of many other countries around the world show that it is possible to enforce regulations of temporary low-skilled worker programs in ways that benefit everyone involved.

Temporary Worker Visas Give Foreign Workers the Opportunity of a Lifetime

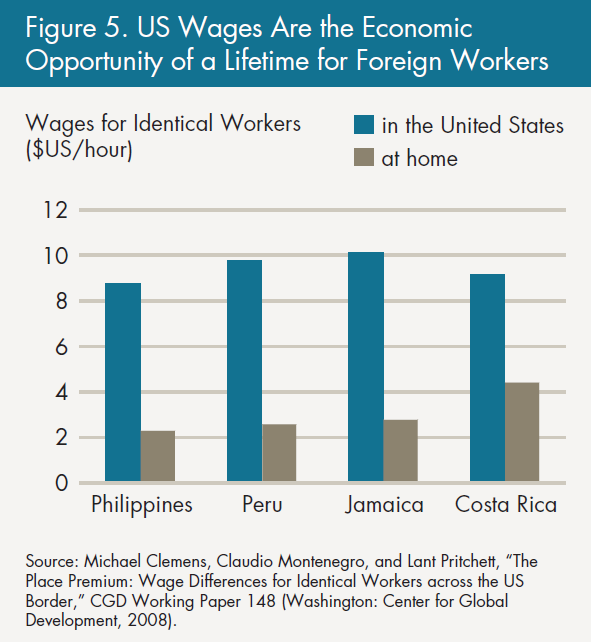

The opportunity to work productively is the best and surest way to help families in the rest of the world escape poverty. In a 2008 paper, we and Claudio Montenegro compare wages of equivalent workers between the United States and 42 other countries. For instance, we measure the wages of a low-skill 35-year-old male born and educated in Peru and compare how his wages would change if he moved from Peru to the United States.

That single move to the United States can change his economic prospects much more than nearly anything else he could do. The typical hourly wage for this person in the United States was $9.74; in Peru it was $2.57 (adjusted for the fact that prices are cheaper in Peru). Even making generous adjustments for selectivity (that those who mover might be intrinsically more productive than those who don’t), we find that the typical low-skillmale worker from a developing country could increase his income by a factor of four—about $15,000 per year—by working in the United States (see figure 5).

A worker’s family back home also benefits massively from his or her work in the United States. Economists have carried out rigorous evaluations of the effects of overseas work on households around the world, including in the Pacific and East Asia. Temporary overseas work raises their buying power, helps them get out of debt, improves their housing, and helps their children get more and better schooling. Of course, workers’ families would prefer there to be good job opportunities in their home countries, but for most, those opportunities just do not yet exist.

While some assert that temporary worker programs exploit foreign workers, the opposite is true. Suggesting that temporary foreign workers are cheap labor is exactly backwards; their labor is cheap at home where it is trapped in a less productive environment but made much more valuable by a legal temporary worker program than by any other real option they have. Of all rigorously evaluated programs to increase incomes in poor countries (education, microfinance, health interventions, business training) the gains from labor mobility are the largest by a factor of ten—and the most cost effective (as they pay for themselves). Of course, there are abuses, and workers need protection from exploitation by traffickers or employers—but a well-designed legal program can do that much better than the existing black markets.

While the gains to foreign workers are not uppermost in the minds of American politicians considering immigration reform, it important to emphasize the fundamental fact that migrants would benefit massively from access to the US labor market—even if only in specific occupations and on a temporary basis.

Conclusion

The immigration reform debate must consider what is best for the American middle class, American low-skill workers, American border security, and foreigners who hope to work in the United States. A well-designed time-bound labor program for low-skillworkers is essential to achieving the best outcome on all four of these fronts. The economic benefits of allowing US firms to access the labor they need will support the American middle class and create more job opportunities for American workers. Replacing ourinformal system with a legal program will improve border security and ensure that the rights of migrants seeking economic opportunities are fully protected. Temporary access to low-skill labor is critical to a sustainable, productive immigration system.

Michael Clemens is a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, where he leads the Migration and Development initiative. His research focuses on the effects of international migration on people from and in developing countries. Clemens has served as an affiliated associate professor of public policy at Georgetown University and a visiting scholar at New York University. He is the recipient of the 2012 Royal Economic Society Prize.

Lant Pritchett is a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development and professor of the practice of international development at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He was previously lead socio-economist in the social development group of the South Asia region of the World Bank. He has published two books with the Center for Global Development, Let Their People Come (2006) and The Rebirth of Education (forthcoming).

Related Publications

Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility by Lant Pritchett (2006), www.cgdev.org/publication/let-their-people-come.

“The Place Premium: Wage Differences for Identical Workers across the US Border” by Michael Clemens, Claudio E. Montenegro, and Lant Pritchett, CGD Working Paper 148, www.cgdev.org/publication/place-premium.

“Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?” by Michael Clemens, CGD Working Paper 264, www.cgdev.org/publication/economics-and-emigration.

“Income per Natural: Measuring Development As If People Mattered More Than Places” by Michael Clemens, CGD Working Paper 143, www.cgdev.org/publication/income-per-natural.

“Split Decisions: Family Finance When a Policy Discontinuity Allocates Overseas Work” by Michael Clemens and Erwin Tiongson, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6287, elibrary.worldbank.org/content/workingpaper/10.1596/1813-9450-6287.

The Center for Global Development is grateful to its funders and board of directors for support of this work.

Lant Pritchett, Let Their People Come: Breaking the Gridlock on Global Labor Mobility (Washington: Center for Global Development, 2006).

Mitra Toossi, “Labor Force Projections to 2020: A More Slowly Growing Workforce,” Monthly Labor Review 135(1):43–64, table 1.

Gordon H. Hanson, “The Economic Consequences of the International Migration of Labor," Annual Review of Economics 1(1):179–208.

See Michael Kremer and Stanley Watt, “The Globalization of Household Production,” Harvard University Dept. of Economics Working Paper (2009); ); Patricia Cortés and José Tessada, “Low-skilled Immigration and the Labor Supply of Highly Skilled Women,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 3(3):88–123; and Patricia Cortés and Jessica Pan, “Outsourcing Household Production: The Demand for Foreign Domestic Helpers and Native Labor Supply in Hong Kong,” Journal of Labor Economics (forthcoming).

Michael Clemens, Claudio E. Montenegro, and Lant Pritchett, “The Place Premium: Wage Differences for Identical Workers across the U.S. Border,” CGD Working Paper 148 (Washington: Center for Global Development, 2008).