Last week, I had the privilege of sitting in on a conference on United States-Cuba relations in Havana that brought together experts on the politics of both countries. The conference was dominated by uncertainty over the future of bilateral ties under a Trump Administration. One of the many prospective casualties of a reversal in US policy toward Cuba would be cooperation on the environment.

The element of surprise

In 2014, this same annual conference was interrupted on December 17th (“D17”) by the parallel announcements by Presidents Obama and Castro initiating the normalization process. The unexpected news was welcomed by most conference participants, many of whom joined a celebratory student march up Havana’s Avenue of the Presidents and down La Rampa.

Many of the speakers making presentations at this year’s conference scrambled to make late revisions to their prepared remarks due to the unexpected outcome of the US election in November. The element of surprise in Trump’s victory was characterized by one Cuban academic as “like a Hitchcock film.”

While much of the early conference discussion centered on understanding the election results—both in general and with respect to the role of Cuban-American voters—conference participants soon turned their attention to the progress that has been made so far in the normalization process, and forward-looking opportunities in areas ranging from commerce to counter-narcotics.

From quid pro quo to mutual interest

One former US diplomat speaking at the conference made the point that the 2014 opening has shifted the frame of US-Cuba relations from one based on quid pro quo—in which each side gives up something in return for a concession from the other—to a recognition of mutual interests.

It is thus perhaps not surprising that among the areas of cooperation that have moved forward most rapidly under the Bilateral Commission established in 2015 are those related to the environment. Among the 15 agreements already concluded and others in advanced stages of negotiation include those focused on environmental cooperation, conservation of marine and terrestrial protected areas, and response to oil spills.

The mutual interests between the United States and Cuba in environmental management are obvious. With a flight time of less than an hour on newly established commercial flights between Miami and Havana, it’s clear that actions on either side of the maritime boundary have implications for both. With shores so close together, better management of fisheries for sustainable harvest, and improved responses to marine pollution are in the interest of Americans and Cubans alike.

There’s also a good match between Cuba’s environmental challenges and expertise that the United States has to offer. Cuba’s natural wealth includes some of the world’s most beautiful coral reefs, as well as unique terrestrial biodiversity, including many endangered species. American scientific expertise and experience in areas such as visitor management in protected areas can be brought to bear on the challenges Cuba faces as it seeks to reconcile economic development and environmental protection.

A change in climate for climate change?

But beyond management of common marine resources and sharing technical approaches to local environmental protection, both countries also share interests in global environmental issues, not least averting catastrophic climate change. Last week’s conference took place in the context of unseasonably high temperatures in Havana, making this year’s contemporaneous International Jazz Festival even “hotter” than usual.

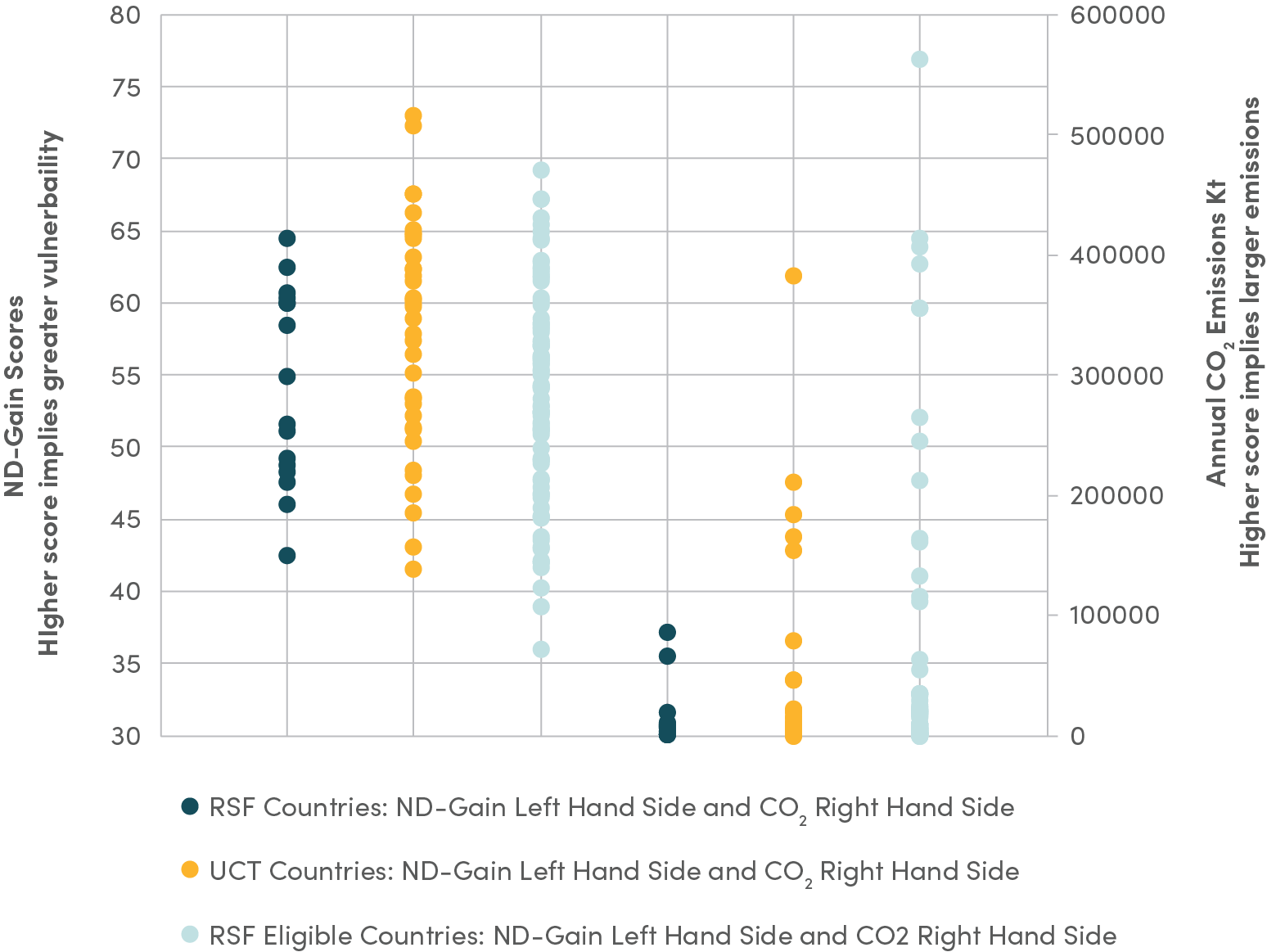

In the opening chapter of our new book, Why Forests? Why Now?, co-author Jonah Busch and I detail how the costs of climate change are being felt first and worst by poor households, and how countries can be knocked off their economic development trajectories for decades by a single storm of the sort that is predicted to become more frequent and more severe. A new US-Cuba agreement to cooperate on meteorology will help both countries forecast such storms more accurately, and provide a broader framework for joint research on climate change.

Cuba, a tropical island nation with economic growth prospects largely dependent on tourism, is particularly at risk from climate instability. Cuba has ratified the Paris Agreement, and has set a target of generating 24 percent of its energy from renewable sources by 2030. A new US-Cuba Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Working Group that met for the first time this month will support achievement of that emissions-reducing objective. To adapt to global warming already in progress, protecting Cuba’s coral reefs and coastal mangrove forests will be an essential element of a strategy to maintain resilience in the face of rising sea levels.

In such mitigation and adaptation efforts, Cuba stands to benefit from multilateral climate finance from institutions such as the Green Climate Fund. Yet the week before the election, Trump announced that he would cancel all such “wasteful climate change spending.”

Drinking expresso, reading tea leaves

During cafecita breaks at last week’s conference in Havana, discussion returned to the implications of a Trump presidency for continuing the process of normalization. Looking back over the two years since the process started, conversations over sweet expresso made clear that in some areas—such as increased investment and trade—aversion to financial risk has hindered progress. In other areas, progress has depended on the willingness of individuals to risk pioneering new relationships under political uncertainty.

But when it comes to deepening cooperation on protecting the environment, the highest risk to stakeholders in both countries is the risk of no action. No matter what happens in other areas of US-Cuba relations, here’s hoping that the new administration recognizes, and acts on, our mutual interests in conserving Cuba’s natural resources and stabilizing the climate.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.