Are “sin taxes” regressive? This is a common criticism of proposals to increase taxes on “bads” such as tobacco, alcohol, and sugar. But there are a number of reasons not to be too concerned by the answer to this question. Ultimately these taxes are designed for health impact, so the financial impact isn’t really the first-order policy question. Our colleague Bill Savedoff has called tobacco taxes the “single best health policy in the world.” Further, what really matters for tax burden is the overall system of taxes on all goods rather than any individual tax.

But still, we were curious. To know the incidence of a tax—who actually bears the cost—you need to know who consumes the good, and what the price elasticity of their demand is. It seems intuitive to us that in rich countries, the poor smoke more than the rich. But is that also the case in poor countries? Aren’t cigarettes too expensive for the poorest of the poor in low-income countries? Is smoking still seen as a marker of high status in some societies?

The best published answer we could find is from a background paper by Rachel Nugent for the Task Force on Fiscal Policy for Health (co-chaired by CGD Board Chair Lawrence Summers). This figure below shows tobacco consumption is higher for the poorest in nine countries, and higher for the richest in four countries.

Figure 1. Prevalence of current tobacco use in the poorest and richest wealth quartiles within countries, 2008-2010

A 2018 Lancet article examined data for 13 countries and found a similar result: more smoking by the rich in eight countries and more by the poor in five.

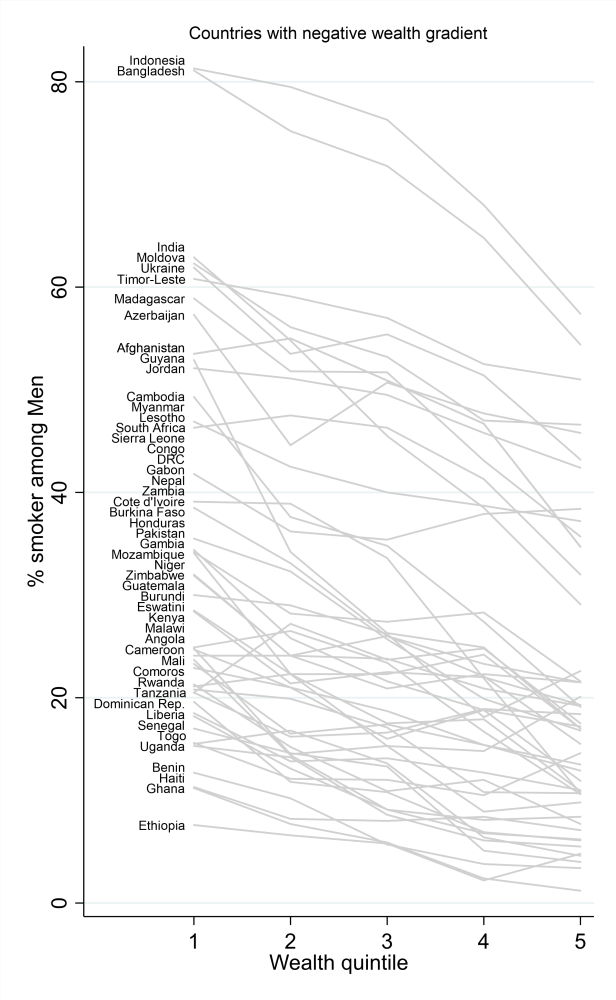

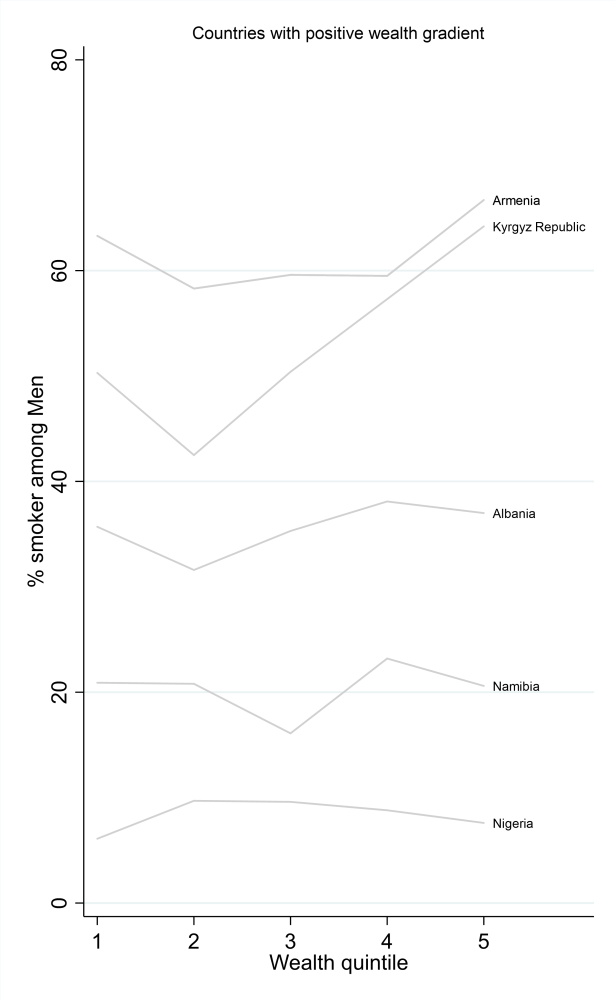

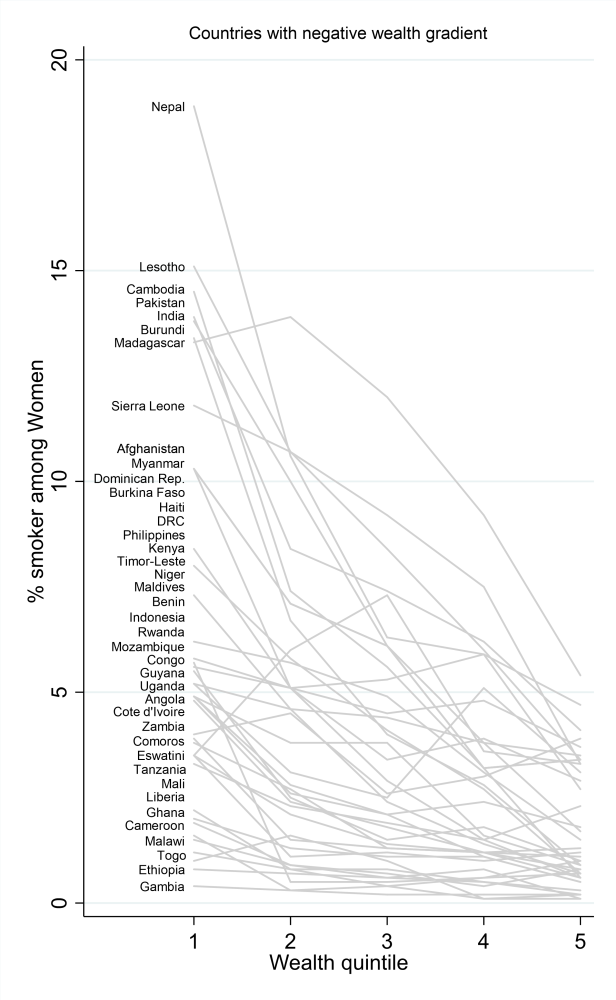

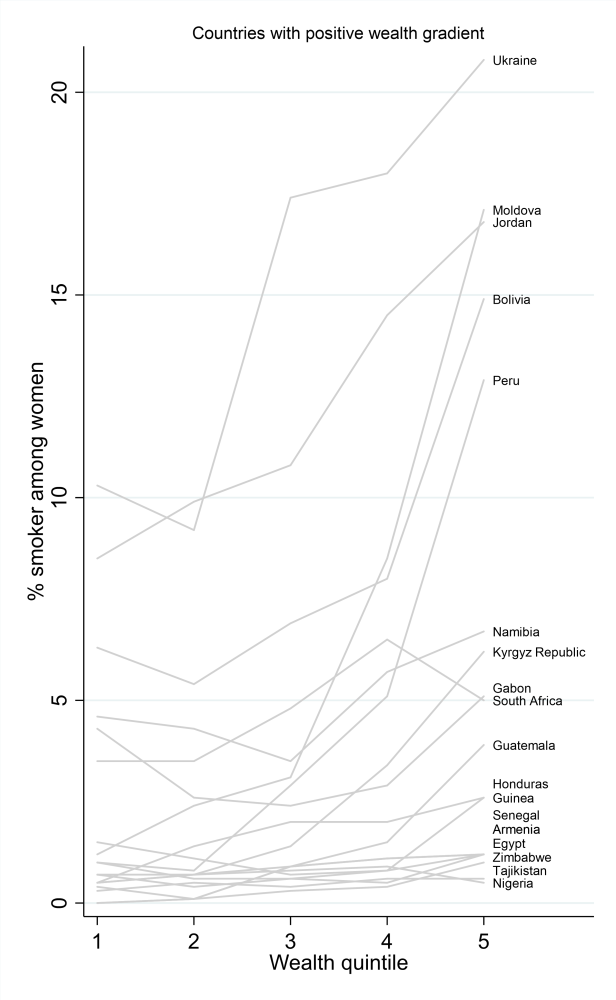

So, a mixed picture. We decided to extend this analysis using all available DHS surveys, covering 59 countries. First, we find that women generally tend to smoke less than men in all countries: four percent of women smoke versus 26 percent of men. In most countries (41 of 59), poor women smoke more than rich women: five percent of the poorest women smoke, compared with three percent of the richest. In an even larger majority of countries (51 of 55) poor men smoke more than rich men: 34 percent of the poorest men smoke, versus 22 percent of the richest. Outlier countries (in which the rich smoke more than the poor) include Kygrz Republic and Armenia for men and women, and Moldova, Ukraine, Peru, Bolivia, and Jordan for women. (We’re all ears to explanations for what is going on in these places.)

Figure 2. In most developing countries, poor men smoke more than rich men

Figure 3. The same is generally true for women

One important detail is that our estimates include smokers of anything, including packaged cigarettes, a pipe, or homemade or traditional cigarettes. If we restrict our analysis to industrial cigarettes only, the difference between rich and poor is less marked. In 12 of 55 countries, rich men smoke more cigarettes than poor ones: 29 percent of the poorest men smoke cigarettes, versus 20 percent of the richest. For women, there are now more countries where the richest smoke more (35 out of 60). Poor people are more likely to smoke tobacco in other forms like pipes or homemade cigarettes, which means a sin tax could have different distributional effects if it applies to all forms of tobacco or only to cigarettes.

So, what did we learn? In contrast to our priors, the poor are more likely to smoke, even in most poor countries. Note that this does not mean that we think tobacco taxes are bad. In fact, if we care most about health benefits, tobacco taxes will disproportionately help the poor. That’s because the poorest are more likely to be unable to afford the healthcare costs that arise from smoking. But we also think these kinds of descriptive facts are important to be able to have the most constructive conversations.

This post was inspired by a lunch talk at CGD by Vageesh Jain, who is conducting a systematic review on the equity effects of sin taxes. We thank Vageesh, Bill Savedoff, and Kalipso Chalkidou for comments on a draft of this post.

For more reading we recommend the World Bank paper “Distributional Effects of Tobacco Taxation” and the accompanying policy note “Is Tobacco Taxation Regressive.”

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.