Recommended

Event

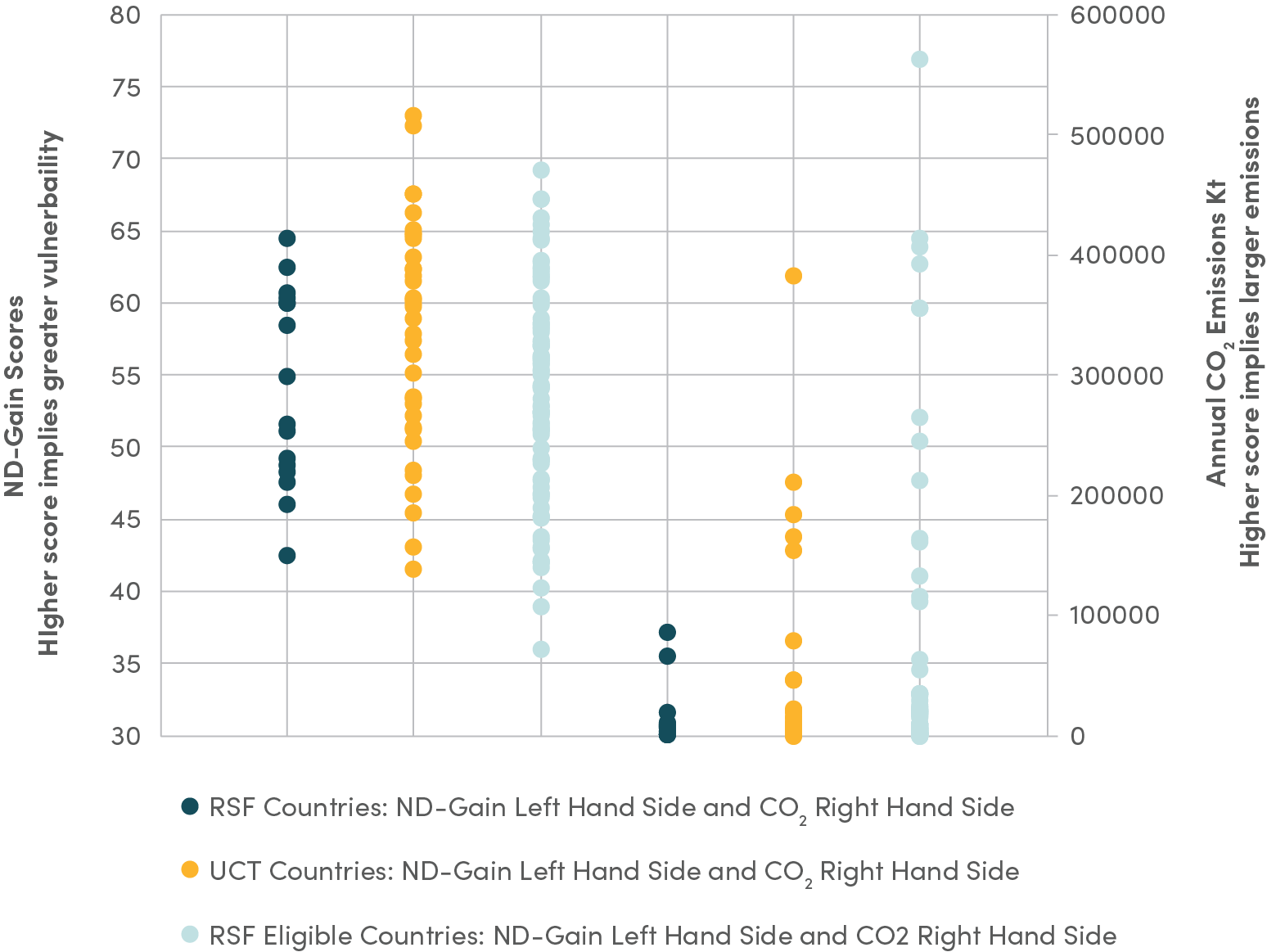

Africa accounts for the smallest share of global greenhouse gas emissions, less than five percent, yet it is widely regarded as being the region most vulnerable to climate change.

That vulnerability will impose significant costs as the region grapples with the impact of global climate change: the continent’s financing needs for adaptation and mitigation are estimated to exceed one trillion dollars per year by 2030.

Yet Africa struggles to mobilize adequate levels of public and private finance for climate action. The billions to trillions agenda, which promised to use billions in public finance to catalyze trillions from the private sector for developing countries, has stalled. Advanced economies have not fully delivered on their commitment to collectively contribute $100 billion each year to assist developing countries in their efforts to cope with the impact of climate change. And the private sector’s contribution to climate finance remains relatively anemic. As a result, the significant potential to raise green investment in Africa remains largely unrealized.

Ahead of COP27, which will take place in Egypt in November 2022, CGD hosted an event that aimed to identify the challenges of mobilizing private finance for climate action in Africa as well as the opportunities and policies needed to overcome them. The discussion provided a platform for eminent experts and senior officials from regional and multilateral institutions to voice their vision of how to make COP successful, while exploring the role of domestic and external stakeholders in optimizing private climate finance for Africa. From the rich discussions, the following messages resonated.

What are the key challenges to raising private climate finance in Africa?

Africa is already on the front lines of the climate fight. For countries across the continent, climate change is not a hypothetical future threat but a daily reality.

Africans face droughts, floods, deforestation, declining agricultural productivity, difficult access to water, rising seas, advancing deserts, and rural exodus. In some cases, some African countries are spending up to 9 percent of their GDP responding to natural disasters caused by climate change. Lake Chad has lost 90 percent of its surface area, leading to five million climate-related refugees moving from Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon as it shrinks.

The adverse growth impact of climate change is also well-documented. Climate change could cause Africa’s GDP to decrease by up to 30 percent by 2050. As a result, climate change is expected to dampen Africa’s prospects for a quick economic recovery and magnify the trends of food insecurity and vulnerability arising from the coronavirus pandemic and Ukraine crisis.

But the continent faces an uphill battle in attracting private climate finance. Notwithstanding the huge opportunity for green investment in Africa arising from the abundance of natural resources and sources of renewable energy, Africa currently receives less than 4 percent of global climate finance, most of which is in the form of loans, rather than grants.

The challenges African countries face in attracting private climate finance are generally similar to those they face when trying to mobilize any other types of private finance: an unstable political context, a volatile macroeconomic situation, or weak institutional and regulatory frameworks. Like other investment decisions, climate finance investment decisions are routinely disincentivized by negative risk perceptions of the continent, which African policymakers typically consider overplayed.

At the same time, there are additional challenges related to the specific types of climate mitigation and adaptation projects for which private finance is being mobilized. For instance, renewable energy power generation projects may face more challenges than conventional power plants in attracting private finance in developing countries with fossil fuel subsidies and inadequate carbon pricing policies.

Moreover, competing priorities and recent and ongoing overlapping crises in Africa are likely to claim public resources that are needed to catalyze private climate finance. The COVID-19 pandemic set back multilateral efforts to tackle other global challenges like climate change, while also crowding out domestic resources allocated to adaptation and mitigation. The Ukraine crisis has worsened this trend. Long-term priorities also provide competition: In addition to the estimated $1.3 to 1.6 trillion needed for climate change every year through 2030, Africa also needs to mobilize another trillion to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

In highly indebted countries, the already heavy debt servicing burden makes taking on more debt to fight climate change a difficult proposition—especially when these countries did not cause climate change in the first place.

How policymakers, businesses and the global community can stimulate private climate finance

First, there is a need for a favorable regulatory and investment environment. African governments have made commendable efforts to improve the business climate, not least by following the World Bank Group’s defunct Doing Business indicators. Still, ample scope exists for reforms to improve the investment environment and reduce the barriers and cost of doing business.

Second, governments should also seize available innovative financing opportunities for blending public and private resources. They could capitalize on financial instruments that have proven to be efficient in raising climate finance, including green bonds and blended finance. While blue and green bonds are already used extensively in financial markets, Africa currently accounts for less than 1 percent of global issuances. To make headways in this direction, the creation of repo market will be critical to stimulate the demand for African green bonds, as advocated by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). The role of regional institutions cannot be overstated in developing blended finance. For instance, the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC), a pan-African development finance institution, has created an infrastructure climate resilient fund focused on climate adaptation to attract more private sector investments toward the continent.

Third, debt restructuring offer potential opportunities for attracting private climate finance against the backdrop of a heavy debt burden and high borrowing costs borne by many countries on the continent. Refinancing existing debt would create fiscal space for green investment projects in African countries. So far, only a handful of African countries have developed such refinancing schemes, including Seychelles which implemented a debt for climate adaptation swap in 2015 followed and issued two years after a blue bond with a partial guarantee from the World Bank.

Fourth, the creation of carbon markets could be critical to raise private finance in Africa. The continent has some of the largest carbon pits of the world, including the Congo basin which is viewed as the second largest carbon sink in the world after the Amazon. But there is a pressing need to build domestic capacity to better assess the scale of these carbon sinks, and to deal with the institutional and governance issues needed to ensure they remain available in the fight against climate change.

Finally, increased transparency is needed from both donors and recipients. On the donor side, there is merit in further clarifying the basis on which climate finance is distributed—whether it will take the form of loans or grants—and how much can truly be mobilized from the private sector. On the recipient side, governance weaknesses, wasteful spending, and transparency over the use of resources made available for climate action all need to be addressed.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.