Lead poisoning is very bad. It mounts a multi-pronged and permanent attack on children’s health—especially the brain and neurological development—during their vulnerable and formative early years. Childhood lead poisoning has life-long effects: cognitive deficits, lower educational attainment, and behavioural disorders. According to widely cited estimates, about one in three children around the world are lead-poisoned, or about 800 million total. Almost all of these children live in low- and middle-income countries.

Exposure to even tiny amounts of lead, invisible to the naked eye, can prove devastating during childhood development. And to eliminate lead poisoning, we need to figure out where those “small” but highly consequential lead exposures are coming from—that is, identifying and eliminating the source of contamination.

The good news is that every country has now banned leaded petrol, which was once the leading source of poisoning worldwide. But the bad news is that many children are still being poisoned—and we don't necessarily know how or why. And surprisingly enough, the best data source to understand the global lead poisoning crisis may be in our own backyard: the New York City Health Department.

Good surveillance systems can help identify sources of lead poisoning

While the burden of lead poisoning is in low- and middle-income countries, it is by no means absent from high-income countries. We know this because many high income countries have domestic surveillance systems, which monitor and report on blood lead levels and—in some cases—monitor lead concentrations in consumer products and the environment. New York City has a particularly good surveillance system. It includes full source analysis following confirmed cases of lead poisoning, as well as sampling of products in stores. And the city publishes its source analysis data, which gives us helpful insights into the consumer product sources of lead poisoning.

There may be lead in your eyeliner…and spices, ceramics, and toys

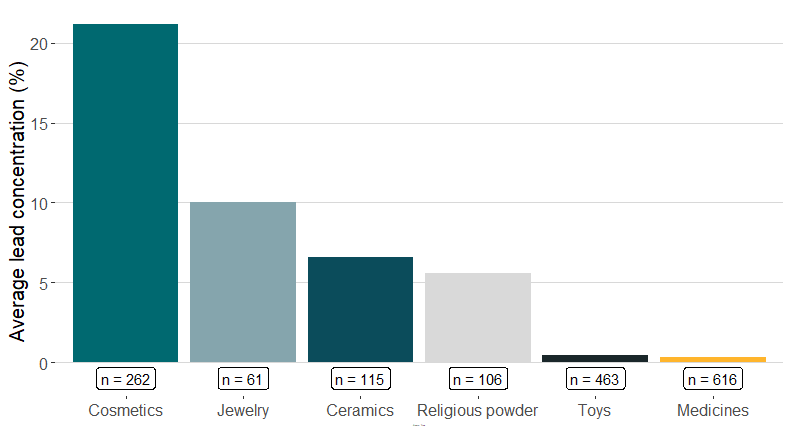

The New York city database analyses the concentration of lead—and occasionally other metals—found in each contaminated product, mostly measured in “parts per million”. We translated this to the percentage of each product that is lead (figure 1). The database contains 4,649 samples of this kind in total, of which slightly more than half had undetectable levels of lead. (We coded these as containing no lead, although technically speaking no product will be entirely lead-free.)

By far the most intensely contaminated products are cosmetics, which can contain more than 20 percent lead. Many of the highest concentration cosmetics are surma (sometimes known as kohl or kajal), an eyeliner used in many countries in Asia, the Middle East and Africa, both cosmetically and medicinally. In some cultures it is applied to infants’ eyes as a traditional “protective” measure.

Figure 1. Lead concentration in consumer products

Note: Authors’ analysis of the NYC database. N refers to the number of samples for each product type.

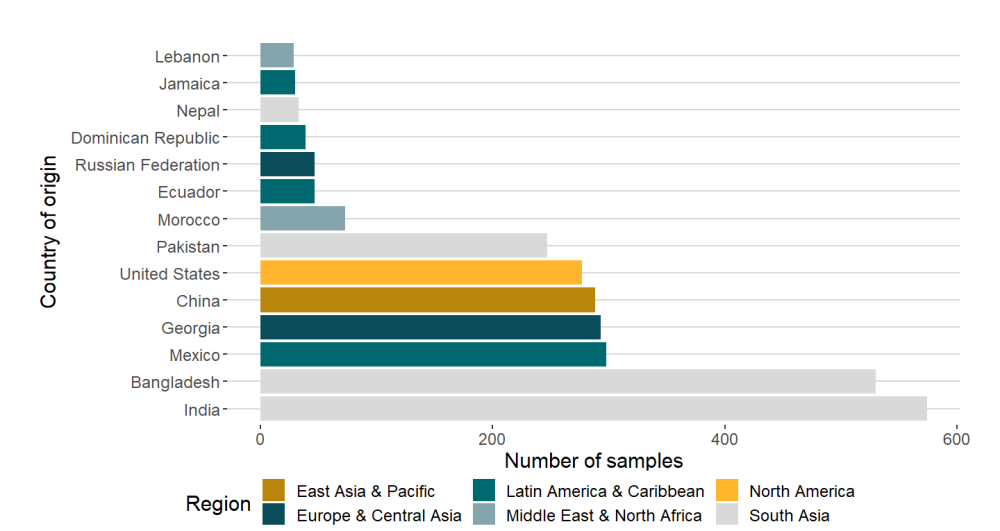

The New York City database analyses the geographical origin of contaminated products. Many originate from within the United States, but also from Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Georgia. Identifying the country of origin can help find sources of contamination in those countries as well as reducing exposure in New York City itself.

Figure 2. Number of contaminated products originating from different countries

Note: Authors’ analysis of the NYC database.

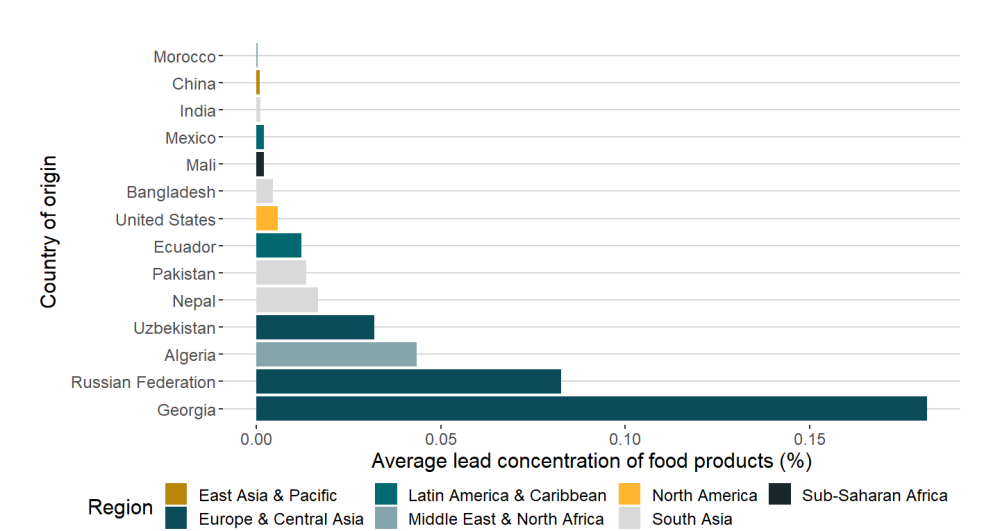

Research on the cause of higher blood lead levels among children in New York City with Georgian ancestry, for example, led to the discovery of high levels of lead in imported Georgian spices (figure 3). This in turn was instrumental in prompting a national survey of childhood blood lead levels in Georgia, run by UNICEF and the Government of Georgia. This survey found that nearly half of all children in Georgia had elevated blood lead levels; source analysis later confirmed that spices were the main source of poisoning. The Government subsequently implemented a range of regulatory and consumer awareness interventions, which have successfully reduced lead levels in spices.

Figure 3. Country of origin of contaminated food products

Note: Authors’ analysis of the NYC database. Only countries with at least ten samples were analysed.

Better source analysis will help eliminate lead poisoning

Since the phaseout of leaded petrol there has been no single main source to blame for lead poisoning. While we have some insights into the remaining primary contributors to lead poisoning, we are still not able to draw firm conclusions about their relative importance either globally or from country to country.

New York City’s data offers indicative insight into the sources of the global burden of lead in consumer goods—but we should not be relying on a single American(!) city to understand a global crisis. Their approach should be widely replicated—both across well-resourced global cities, and within the highest-burden countries themselves.

It’s up to all of us to track down the sources of lead poisoning and remove them from the market—protecting current and future generations from this tax on children’s potential to learn and thrive.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.