Recommended

CGD NOTES

September 18th marks the world’s first International Equal Pay Day, which calls attention to the importance of achieving equal pay for work of equal value for all people regardless of gender, age, disability status, and other characteristics. The United Nations’ recognition of this day is itself a reflection of the heightened attention the issue of equal pay has received across countries in recent years, but there is much more to be done to achieve its objective. To that end, in collaboration with the Open Data Charter and The B Team, we have prepared a joint policy memo that identifies roles for government and the private sector in closing gender pay gaps. Below, we summarize our recommendations.

No country has closed the gender pay gap.

Though the share of women’s participation in the labor force has increased over the past thirty years, women, on average, continue to be paid 20 percent less than men with gaps varying by region and country, and worsening along the lines of race, ethnicity, and other demographic characteristics. Now, the COVID-19 health crisis, coupled with the economic downturn, threatens to exacerbate these gaps.

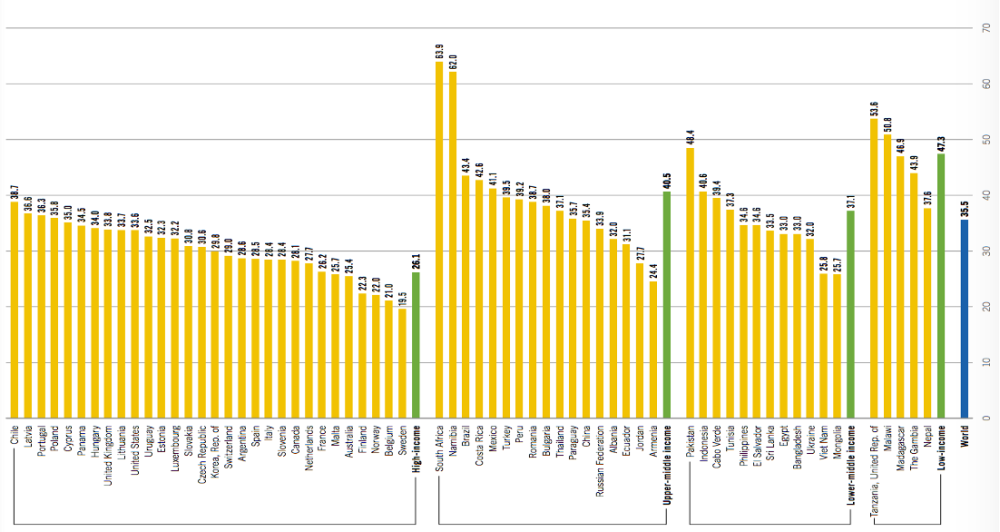

Figure 1. Wage inequality varies between and within the four income classes

Source: ILO: Global wage report 2018/19: What lies behind the gender pay gaps. Lower values (closer to zero) indicate lower levels of wage inequality and higher values (closer to 100) indicate higher levels of wage inequality.

Everyone stands to gain from closing the gender pay gap.

With higher earnings, women’s own welfare, agency, and opportunities have the potential to improve. This can, in turn, benefit their households and communities, because women invest more money than men into the education and health of their children—creating a virtuous cycle of development. Increased earnings for women also benefits governments (through increased tax revenue), businesses (through increasing purchasing power/consumer spending), and the wider economy.

What’s behind the gender pay gap?

Unfortunately, closing the gender pay gap is easier said than done. Several barriers and challenges exist, including:

1. The “motherhood penalty”: Unpaid care and domestic responsibilities impact the career progression of women.

After giving birth, women’s pay lags behind the pay of similarly educated and experienced men and women without children. Among married, full-time working parents of children under age 18, women still spend 50 percent more time than men engaging in care activities within the home. In lower-income contexts, unpaid care work burdens compound due to limited energy and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, adding to the time women must spend on domestic responsibilities. Indeed, women around the world spend 200 million hours daily collecting water for their households, further limiting the time they have for non-domestic tasks, including work and school.

2. Occupational sex segregation, coupled with the systemic undervaluation of “women’s work,” results in women-dominated industries and jobs attracting lower wages.

Women and men are concentrated in different sectors and positions. For example, women are more likely to be nurses, and men doctors. Women are more likely to be early childhood educators, and men professors. But women also make up a disproportionate percentage of workers in the informal sector (e.g., domestic workers), leaving them without any protection of labor laws, or social benefits such as pensions (creating the conditions for pensioner poverty), health insurance, or paid sick leave. Consequently, they are at a higher risk of having their wages withheld arbitrarily, receiving wages below the minimum wage, and experiencing sexual harassment, among other problems.

Women are more likely to enter and remain in lower-paid occupations with fewer opportunities for advancement for many reasons including: (1) being tasked with unpaid care work responsibilities that limit their capacity to work in certain formal and high-paying occupations, and (2) being socialized into feminized roles (occupations that traditionally have a large percentage of women workers).

Additionally, jobs women perform may be paid less precisely because women do them. When women enter an occupation dominated by men, wages tend to fall. Men appear to fear that if women move in, the work will be deemed to have become easier and less worthy of decent pay and status. This highlights the need to rethink how society values the work women typically perform.

3. Discrimination and bias in hiring and pay decisions.

Many companies’ recruitment processes are either gender-biased through their job advertisements and algorithms, or rely heavily on professional networks, given that people tend to recommend others similar to themselves for positions. For executive high-tech jobs, referred candidates are much more likely to be men than women, limiting women from integrating into the high-paying, men-dominated technology space.

Beyond recruitment processes, employers may discriminate in pay when they rely on past salary history in hiring and compensation decisions, meaning pay decisions influenced by discrimination can follow women from job to job.

Calling all stakeholders to act

Addressing the barriers outlined above will require collaboration between governments, the private sector, and civil society organizations and labor unions, such as through multi-stakeholder forums like the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and the Equal Pay International Coalition (EPIC).

Our proposed solutions for governments include:

1. Adopt and model best practice through the public sector workforce.

Public sector employment accounts for 45 percent of all formal employment in low-income countries, and between 20 and 40 percent in middle-income countries. Eliminating gender pay gaps in the public sector would go a long way toward narrowing overall gender pay gaps, both directly and through modeling to private sector companies on how to take effective actions.

2. Legislate a minimum living wage.

Governments that set a minimum living wage—one that allows workers to adequately cover living costs—have been shown to reduce earnings inequality across demographic groups. Also, minimum wage legislation offers a set of standards for labor unions to aim for when advocating for improved conditions for informal workers.

3. Legislate to mandate data publication on wages and overall compensation.

Evidence suggests that gaps shrink when companies are required to disclose them. The data published should incorporate intersecting demographic characteristics, including race, age, and disability status.

4. Legislate to prevent companies from requesting data on salary histories.

With historically lower wages comes a disadvantage in being able to negotiate for more compensation if salary history is disclosed. To ensure that job candidates have the information they need to assess whether a role fits their skills, experience, and financial compensation needs, firms should provide a transparent salary range for positions they seek to fill.

5. Invest in policies and programs that address occupational sex segregation.

Governments should consider setting targets or providing incentives for firms that hire more women in men-dominated sectors and vice versa. Governments can also prioritize job training and placement, providing necessary support for women to cross over into men-dominated fields.

6. Invest in social protection, parental leave, and public services.

Social protection schemes, low-cost or free services for childcare, the elderly, and people with disabilities should be prioritized, improved, and expanded. Such investments are vital to redistributing the unpaid care work that keeps many women out of the labor market, in part-time positions, or in precarious work.

Our proposed solutions for business include:

1. Commit to and ensure equal pay for equal work.

Efforts to close pay gaps should include an annual audit of pay that is disaggregated by gender and other demographic characteristics. Businesses should also explore working with governments and platforms like OGP to advocate for binding legislation to ensure equal pay for equal work.

2. Address bias in the system to permanently close pay gaps.

When using advanced hiring platforms, companies should consider whether these tools actually result in more equitable, diverse, or gender balanced hiring outcomes. Without intention and oversight, hiring algorithms and technology platforms can introduce and reinforce gender and racial stereotypes.

3. Update and establish new policies that are gender-neutral and family friendly.

There is a positive relationship between paid parental leave and employee retention. Businesses should also confront the notion that care work is “women’s work” and actively encourage men to take advantage of parental leave.

4. Commit to gender balance in leadership and the broader workforce.

The lack of women in leadership roles contributes to the poor sense of belonging and isolation many women feel in male-dominated workplaces. While increasing the number of women in leadership is critical, it is equally important to establish a gender-responsive and inclusive culture throughout the company, including among low-wage and underrepresented workers who may face additional forms of discrimination.

5. Provide salary ranges for new positions.

Posting salary ranges will help ensure that women and other candidates who have traditionally faced discrimination are better equipped to negotiate. Showcasing salary ranges up front and providing the space to have conversations about pay will save time for both parties and foster trust through transparency.

6. Provide development and network-building opportunities.

On average, women and people of color do more “office housework” and have less access than white men to the opportunities they need to advance in their careers. Businesses should consider establishing rotational programs and sponsorship schemes to support the upskilling and development of all employees, with a special focus on women and people of color.

We hope that these initial recommendations allow for more in-depth conversations about context-specific opportunities for progress, as well as concrete commitments by government officials, business leaders, and civil society organizations that result in meaningful change. For more detail, check out our memo here.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Juan Arredondo/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment