In the summer of 2003, the West African nation of Liberia was facing a humanitarian calamity. After 23 years of war, the regime of warlord-turned-president Charles Taylor was crumbling. Rebels in the south controlled the second-largest city and were creeping toward the capital’s airport. Another rebel group, led by a fighter calling himself General Cobra, was advancing from the north and seized the capital’s main port and the country’s lifeline. Displaced civilians crowded into the increasingly tight peninsula of Monrovia as stocks of fuel, food and medicine dwindled. The city waited for a rebel invasion. Peace talks in Ghana ended abruptly when a UN Special Court unsealed an indictment against Taylor for war crimes in Sierra Leone. Taylor returned to Liberia, cornered diplomatically and militarily. A tragedy loomed. Would Taylor make a bloody last stand?

The international diplomatic corps and most humanitarian organizations had fled the country. The last remaining outpost was the U.S. Embassy, a compound at Mamba Point in the heart of the city. Ambassador John Blaney and a hardy band of embassy staff fought to keep the post running and to give diplomacy a final chance.

Blaney and Co. faced many foes. Taylor’s government was corrupt, venal, and delusional. He deployed militias of conscripted child soldiers, many too small to carry their weapons. The rebels were mysterious and unpredictable, often drugged and with unclear loyalty to their supposed political leaders. Even if a peace deal could be reached on paper, would anyone go along?

But the most interesting battle was with Washington DC. With wars raging in Iraq and Afghanistan, the last thing the United States wanted was to deploy troops to West Africa or get dragged into another armed conflict. The Defense Department in particular didn’t want to have to rescue the stubborn Ambassador and his staff. Secretary Donald Rumsfeld pushed hard to close the post and walk away.

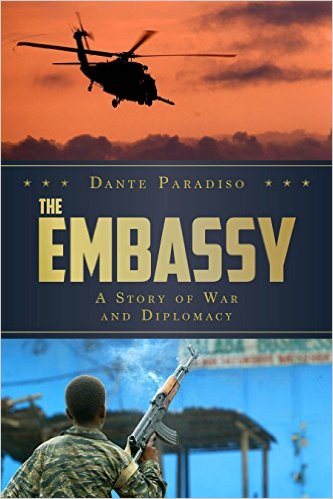

The Embassy: A Story of War and Diplomacy by Dante Paradiso tells the inside story of how Blaney and his team kept the embassy open, risked their lives to cross the front lines to meet with General Cobra, and played a crucial role in negotiating a complicated sequence that included Taylor being forced into exile, the rebels allowing ECOWAS peacekeepers to reopen the port, and getting peace negotiators back to the table.

Paradiso, a foreign service officer who served in that embassy, skillfully tells the story through the eyes of several unsung heroes: the ambassador, a defense attaché, a diplomatic security officer, a local Liberian staffer, and a humble and unnamed “Political Officer” that can only be the author. Although the book is nonfiction, it keeps pace like a thriller and includes just enough context to keep the reader well-informed without bogging down the story. The dialogue between the officials is authentic and at times jarringly human. The Embassy is a riveting quick read and a dramatic firsthand account of a fascinating and frightening series of events. I’d recommend it alongside other recent books on Liberia, such as Helene Cooper’s The House at Sugar Beach, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s memoir, This Child Will Be Great, and Riva Levinson’s Choosing the Hero (see my previous review of that terrific book).

As a policy analyst and former diplomat, several aspects of The Embassy’s tale especially caught my attention. First, is the unheralded courage of the embassy staff. The ambassador and his colleagues faced immense personal danger to represent their country and to save innocent lives. This is a must-read for anyone who thinks diplomacy is about fancy cocktail parties.

It’s also striking how the U.S. Embassy plays a unique role in some parts of the world. Liberia has a special history with the United States and American influence is unusually high. But the embassy grounds were a haven of stability and an outpost of hope, both physically and symbolically. If the post had been closed, it would have meant the likely death of tens of thousands of people and a disaster that we would still be dealing with—and no doubt apologizing for—today.

Foreign policymaking is often messy, but Paradiso’s story is startling for how often the embassy is unaware of what’s happening outside a narrow slice of central Monrovia or even back in Washington. At several points, the ambassador learns of U.S. policy decisions, including the imminent arrival of protective troops, via the media. The embassy staff appear to have only the vaguest outlines of the policy battles underway between the White House, State Department, and Pentagon.

That partly explains why the story sheds no light on one of the decisive factors in the outcome: why did President George W. Bush take such an active and firm line on Liberia? In the midst of multiple foreign policy crises, the President repeatedly made the point of insisting publicly that “Charles Taylor must go.” I would have loved to know the full story of what happened behind the scenes and why Taylor eventually agreed to leave. Then national security advisor Condoleezza Rice and NSC senior Africa director Jendayi Frazer were obviously central, yet they barely get a mention. But I suppose that’s partly the point of the book: the embassy was in many ways flying blind.

Finally, for developmentistas who worry about greater State Department control of aid programs, there’s an amusing section (pages 219-220) where the ambassador cooks up a recovery plan on the spot. He wants a demobilization plan, cash for education, and a public works program. How much? One hundred million is his first answer. Nah, he thinks. “Let’s go for two hundred million!”

We now know that those tense and tenuous weeks back in June-August 2003 would eventually lay a foundation for democratic elections two years later that brought Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to power and the beginning of the country’s recovery. Today, Charles Taylor is in prison and Liberia is considered largely a post-conflict success. The Embassy shows how close the line between triumph and tragedy can be—and how a few brave people can make the difference.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.