Recommended

COP27, just concluded in Sharm El-Sheikh, was dubbed the ‘implementation COP’ by its Egyptian hosts. But it’s very difficult to implement without workers. The COP27 agreement emphasises that a “just and equitable transition” must include “workforce and other dimensions.” This short, vague language covers a vast and urgent challenge that requires policymakers worldwide to collaborate on a solution.

Spending on climate-friendly investments including infrastructure is indeed on the up, which is good news for the planet. In the United States, for example, the recent Inflation Reduction Act allocated nearly half a trillion dollars for green transition needs, incentivising the scaling up of clean energy production and energy use reduction. Spending is easier now that it makes short-term as well as long-term sense. In Europe, payback times for renewable investments have fallen rapidly due to rising energy costs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The UK, spurred by more than £13 billion in annual waste due to poor home insulation, is moving to cut energy demand by 13 percent by 2030 through a massive retrofitting scheme.

Retrofitting, construction, operation and maintenance of all of this new infrastructure will take people. The clean energy sector alone already employs more workers than the fossil fuel sector does, and the gulf will continue to grow. And a recent study by Stanford’s Mark Jacobsen and colleagues estimates that a shift to a global net zero emissions economy would involve the creation of 55 million new jobs worldwide in construction and operation. The UK’s new insulation programme alone is expected to require tens of thousands of new energy and construction workers.

But unless we ensure that skilled workers are available to carry out such projects, they will fail.

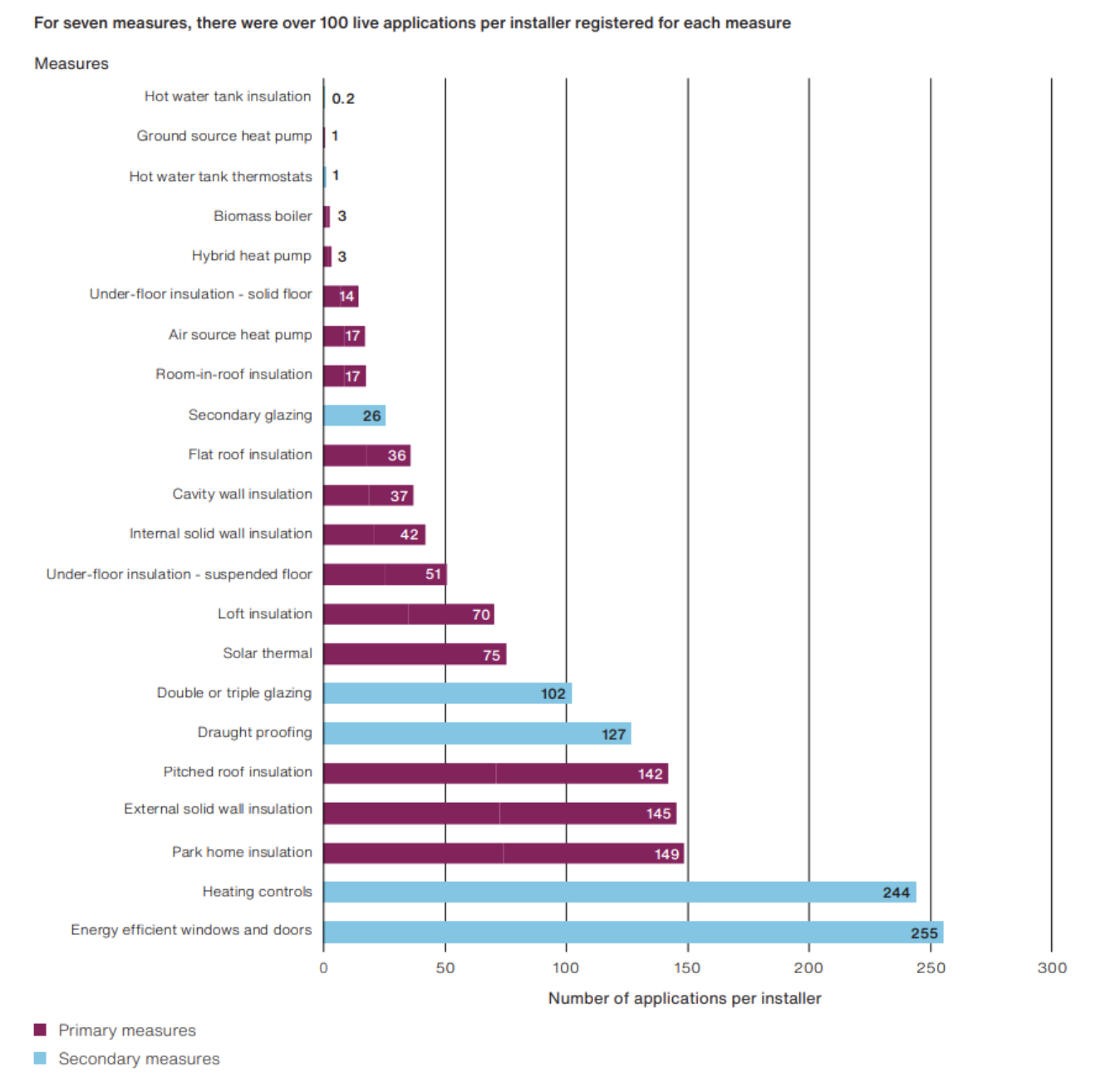

An earlier £1.5 billion home insulation scheme failed to meet its targets in part due to woefully inadequate skills availability—in some cases resulting in more than two hundred customer applications per registered installer (see figure below). This is a symptom of a global problem. The International Energy Agency reports that a lack of skilled workers is a bottleneck in the green transition projects worldwide: “companies [lack] the skilled workforce needed to deliver these projects [...] Shortages of skilled labour across energy supply chains are already translating into project delays and impacting investment decisions.” And in a May 2022 report, the European Commission noted that in the solar sector “there is already a lack of skilled workers’, and that “this bottleneck could grow quickly if unaddressed.”

While there is uncertainty about the exact scale of the global shortage and the applied skills mix required, the world as a whole urgently needs more people with the right training and expertise to fill the gap. That is a particular challenge for the Global North, responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions but also where working-age populations are shrinking. In Europe, for example, there will be 95 million fewer working-age people in 2050 than in 2015 under business-as-usual (contrast India, where there will be about 199 million more). While some green economy jobs can and should be created by retraining workers previously employed in declining industries like fossil fuel extraction and use, Jacobsen and colleagues’ study suggests a global net zero economy would create demand for two new jobs for each one lost.

Figure 1: Ratio of live applications per registered installer for each measure, Green Homes Grant Voucher Scheme, September 2020 to March 2021.

Source: UK National Audit Office, 2021

The solution

We face a global skills gap compounded by a growing shortage of working-age people in the countries where the net zero transition is most urgent. The solution is to provide green skills training to people in countries where the working-age population is still growing and enable some of those trainees to fill employment gaps in the countries where working-age populations are shrinking.

The Global Skill Partnership (GSP) model, developed at CGD by Michael Clemens, proposes a way in which this could be managed. The 2018 Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration recognises their usefulness. These partnerships

- involve an ex ante bilateral agreement…

- …established between public and private institutions…

- …aiming to link skill creation and skill mobility in such a way that…

- …migrants, countries of origin and countries of destination all benefit from the partnership.

They foresee that a share of those acquiring skills will migrate to work in the country of destination—which funds the scheme—while the rest remain in the country of origin. If the scheme is well-aligned with the needs of the sending and receiving labour markets, all parties benefit. Destination countries fill skills gaps, and do so at relatively low cost. In 2021 the cost to the government of training a nurse was £26,000 in the UK, versus US$6,000 in Kenya; there is no reason to think that similar differences in training costs would not exist in the case of green skills. Migrant-sending countries also benefit from an increased pool of skilled workers, because many trained as part of partnership programmes remain at home. In addition, they benefit from a stream of remittances sent home by those who migrate. Trainees get access to better-paid jobs and a higher standard of life whether they leave or stay.

The green-skilled mobility paradigm shift

Skilled migration is often inaccurately seen through a zero-sum lens of brain-gain and brain-drain, a “fight for talent”, in which countries compete for the best minds, and the migrant-receiving country benefits to the detriment of the sending country. That has always been misguided: migrants generate remittances and help forge trade and investment links, and the opportunities that migration present are a powerful motivation to get trained in the first place. But models like Global Skill Partnerships help guarantee a ’triple-win’ outcome, and in the case of green-skilled mobility, they can go one better: a quadruple win for migrants, sending and receiving countries, and the global public good of a healthy climate. Where a combination of training and migration helps alleviate bottlenecks constraining the green transition, the benefits accrue to all countries, not just those involved in a skills partnership.

There are many questions to be resolved. Where can green-skilled workers most effectively be trained? What about skills accreditation? What are the most important training needs and costs? Where will demand for green skills be highest in the future? (Nigeria, for example, is expected to see high population growth and increased energy consumption; might it be more efficient in emission-reduction terms to train green-skilled workers there than in comparable countries with lower future energy needs?). How would funding work? (We have some ideas). Could such programmes also help those affected by climate-related displacement to access a better life? (We think they probably could— offering a combined mitigation and adaptation solution). Could these programmes be usefully combined with other efforts targeted at fragile and conflict-affected states? (Probably—they’re already calling for help in growing decentralised energy access, and skills will be a bottleneck).

The research to answer these questions needs to come fast: studies, pilot programmes, and scaling are urgent and necessary if we are to meet the labour market challenges ahead. The potential gains are enormous; the costs of doing nothing are larger still.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.