Recommended

Today is International Safe Abortion Day—and its observance comes at a critical juncture for women’s reproductive autonomy worldwide. Earlier this year, the Texas legislature passed a law severely curtailing a woman’s right to access an abortion within the state, and on September 1st as the law went into effect, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to block its implementation. But just a week later, the Supreme Court of Mexico moved in the opposite direction, unanimously ruling that penalizing abortion is unconstitutional under Mexican law. How do these two recent examples compare to global trends? Are governments around the world gradually increasing protections around women’s right to reproductive autonomy, or are the restrictions on the right to choose imposed by the Texas legislature reflective of a broader global backlash?

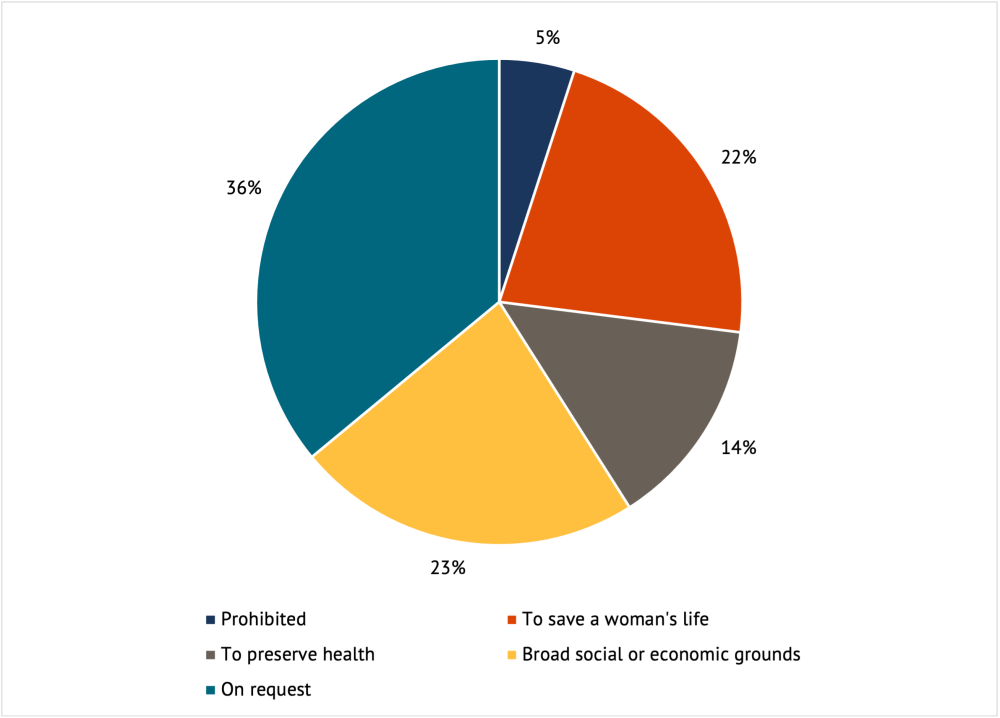

The Guttmacher Institute has said that 2021 is “already the worst legislative year ever for US abortion rights.” In the United States, within the first half of 2021, 90 abortion restrictions had already been enacted—the highest number in a year since Roe v. Wade in 1973. But evidence shows that, with some exceptions, Texas and the U.S. are running counter to a global trend to expand abortion rights. Over the past 25 years in particular, the global trend has overwhelmingly been that of liberalization of abortion laws, with 18 countries overturning complete bans on abortions and 15 countries reforming laws to allow abortion upon request.

Figure 1: Percent of the world’s population of reproductive-age women living under different abortion regimes

This year alone, we have seen progress on abortion rights, for example, in Argentina (voted to legalize abortion up to 14 weeks), South Korea (decriminalized abortion), Thailand (decriminalized up to 12 weeks), India (less restrictive timing), and Mexico (decriminalized). Argentina has built on its own domestic legal advancements by asserting global leadership on the issue of reproductive autonomy; through the recent Generation Equality Forum, the Argentine government made a commitment aimed at “promoting the decriminalization of abortion and the elimination of legal and political barriers to abortion, including self-managed abortion, in as many countries as possible.”

One thing these countries have in common is more women in government. In 2020, South Korea elected over 57 women to Parliament—the highest number in its history. Women make up 39 percent of Argentina’s Congress, a proportion that has increased since the passage of a law requiring the Congress to include 30 percent women in 1991. As of 2021, Mexico’s Congress is half women, and in India, the number of women elected to Parliament has been setting records each year since 2014.

Figure 2: Women’s representation in parliament and abortion regimes

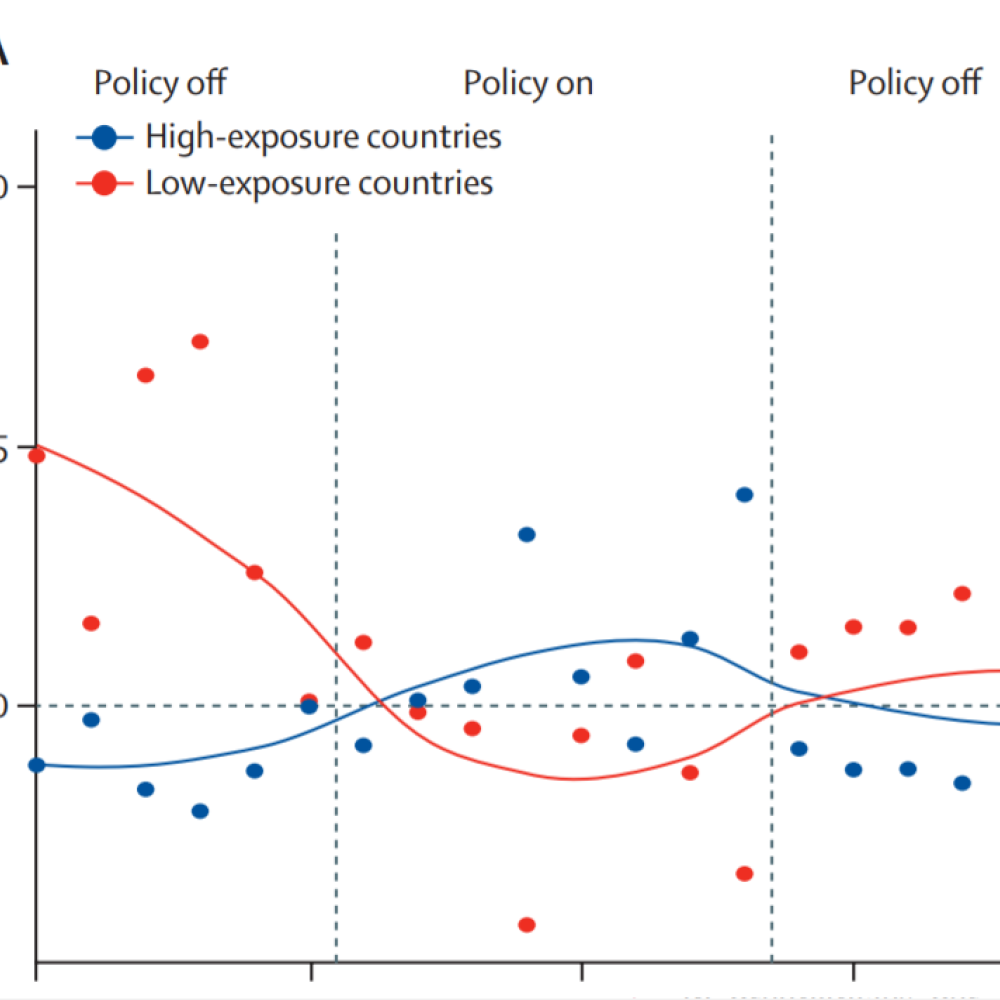

The data tells us that there is a correlation between parliamentary seats held by women and liberalization of abortion laws, as shown in the figure above. Of the 193 countries for which we have data on abortion laws and on parliamentary seats held by women, about 36 percent allow abortion on request, and of those countries the average proportion of parliamentary seats held by women is 26.7 percent. Of the two most restrictive groups, where abortion is prohibited altogether or only permitted to save a woman’s life, the average proportion of parliamentary seats held by women is 18 percent. While this analysis does not imply causation, it complements other evidence establishing that when more women are elected to positions of power, the issues women tend to care about are given more attention. Research from India showed that increasing women’s representation on local village councils increased the provisioning of resources for essential resources, including drinking water. A study in Sweden found that a higher proportion of women elected to local assemblies was associated with more gender-equal outcomes in income levels, the uptake of full-time vs. part-time work, and parental leave policies.

But despite advancements around legal protection for abortion, and the progress in women’s political leadership that perhaps underlies them, now is not the time to let the foot off the gas in ensuring women’s and girls’ reproductive autonomy. In addition to the politics surrounding abortion, we have tracked the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare systems, including the ability to access safe abortion services, through CGD’s COVID-19 Gender and Development Initiative, and it’s clear that the consequences of a “COVID crowd out” effect extend to abortion access.

Early projections from the Guttmacher Institute warned that a 10 percent reduction in access to short- and long-term reversible contraceptives would result in an additional 49 million women with an unmet need for modern contraception in low- and middle-income countries and an additional 15 million unintended pregnancies, alongside more limited access to safe abortion services. The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) projected that, depending on the level of service disruption, just three months of lockdown could result in 13–44 million women losing access to modern contraceptives, with unmet need and unintended pregnancies increasing dramatically with the duration of lockdown and service disruption. In August 2020, Marie Stopes International cited data that 1.9 million women and girls lost access to contraception and safe abortion services during the first half of the year across 37 countries as a result of COVID-19.

We have seen these predictions play out at country level. In India, safe abortions dropped by 28 percent, which in part may be due to disrupted access to medical versus surgical abortions during the response. In Ethiopia, a case study from a tertiary referral hospital in Addis Ababa observed a 27 percent decline in patients presenting for family planning services as well as reductions in safe abortion services and comprehensive abortion care by 16.4 and 20.3 percent, respectively, when comparing March-May 2020 utilization data to the same time in 2019.

And with abortion as a microcosm, the story on broader sexual and reproductive health services and rights (SRHR) in 2021 is similarly mixed. On one hand, some governments made strong commitments through the Generation Equality Forum to support SRHR globally, holding the line on their contributions to organizations like UNFPA and the International Planned Parenthood Federation. The Biden administration has repealed the Mexico City Policy (yet again) and will be able to fund healthcare providers in lower-income countries more flexibly and more effectively as a result. But on the other hand, we see some countries, like the United Kingdom, retreating from global leadership on SRHR through their recent aid cuts, including to UNFPA, and without Congressional action, the Mexico City Policy will continue to be a political football between Republican and Democratic administrations in the US. This is situated against the backdrop of COVID-19—a crisis that has had consequences for women’s and girls’ ability to access not only safe abortion services but also contraception and other sexual and reproductive health services.

While data reflects increased access to safe and legal abortion across the globe in recent decades, the example of the United States underscores that linear progress is not guaranteed—and the leadership coming from Argentina, Mexico, India, Thailand, and elsewhere reflects that advancements are by no means concentrated in high-income countries. The past two years have also shown us that access to abortion isn’t just limited by restrictive legislation but also by crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. To achieve a gender-inclusive COVID-19 recovery, women will need access to essential health care services and agency over their own futures, including when to have children. Access to a full array of sexual and reproductive health services and rights must be included in any gender-inclusive COVID-19 recovery agenda.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Yagazie Emezi/Getty Images/Images of Empowerment