Recommended

Countries have repeatedly committed to refugees’ right to work, beginning with the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and as recently as the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees. When upheld, access to labor markets can not only improve incomes and mental health for refugees, but also boost growth and job opportunities for host communities.

Yet, despite the strong ethical, legal, and economic arguments for economic inclusion, refugees’ work rights are often not upheld. Barriers abound, from strict encampment to bureaucracies unable to distribute work permits. In some countries, these barriers to labor market access are a result of the country’s laws, whereas in others it's a failure of implementation.

Today we published the 2022 Global Refugee Work Rights Report, a joint report with Asylum Access and Refugees International that documents and analyzes these barriers globally in detail. We describe the extent to which refugees have the right to work, both in law (de jure) and in practice (de facto), in 51 countries. This blog introduces our findings, but please do dig into the report, website, and data to learn more.

What we did

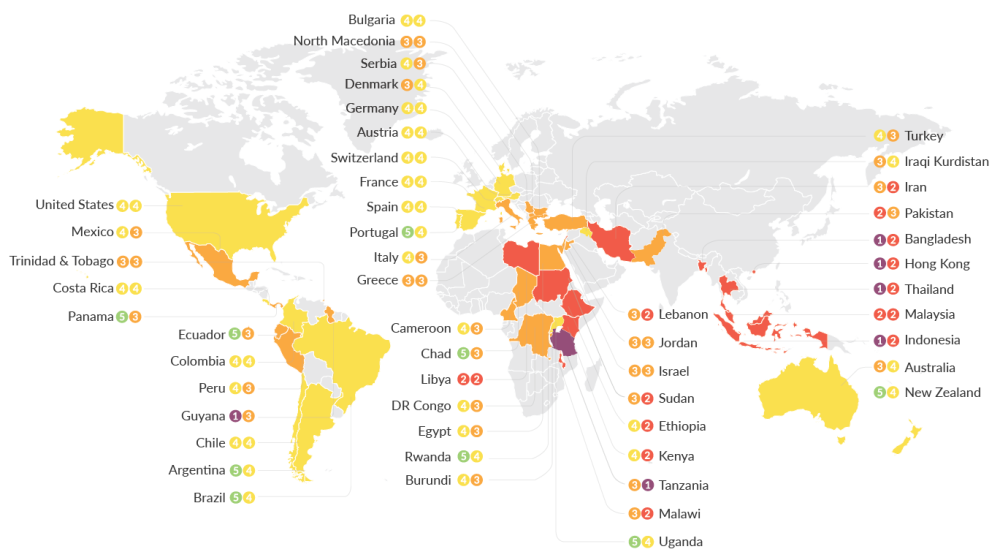

The basis of our de facto analysis is a survey conducted in 2021 on the reality of labor market conditions; the responses to our survey determined the entire sample of countries covered in the report (Figure 1). We include the 51 countries where we received at least three responses, which account for 87 percent of the global population of refugees, asylum seekers, and Venezuelans displaced abroad in 2021. We define “refugees” as all foreign-born people displaced by conflict, which includes asylum seekers and Venezuelans displaced abroad, in order to standardize across countries.

Figure 1. Scorecard map

Note: Countries are shaded based on their overall de facto score in the 2021 Refugee Access to Work Rights dataset. Countries are listed with their de jure score, left, and de facto score, right.

We assign each country an overall de jure score and an overall de facto score, each on a 5-point scale. For the de facto score, we rely on the survey, which asked practitioners about refugees’ de facto access to wage employment, self-employment, freedom of movement, rights at work, and other factors of economic inclusion. We reviewed the survey data alongside secondary sources, and used each of these individual factors to calculate a weighted average for an overall de facto score.

For the de jure score, we developed a comparable 5-point scale and then conducted a desk review of available legal sources. More details on the definitions of each score, methodology, and survey instrument are available on our website and in the report. We also provide narrative descriptions of each country’s de jure and de facto environment as scorecards as Part 2 of the report, which are also available on refugeeworkrights.org.

What we found

At least 62 percent of refugees live in countries where the legal framework for their right to work is adequate, meaning the country received a 4 or a 5 (Figure 2). This is a lower bound because 13 percent of refugees live in countries that are not scored and could also have adequate de jure environments. Forty of the 51 countries have a law or policy where at least some refugees can access the labor market, and 30 countries explicitly permit refugees to work.

However, many of these countries fall short in practice. At least 55 percent of refugees live in countries that significantly restrict work rights in practice, scoring a 3 or below on our scale (Figure 3). And 25 countries receive a lower score in practice than in law, meaning that while a positive legal environment may be in place, refugees aren’t necessarily seeing their rights in action. No country received the highest score for the de facto measure, as each country in our sample imposes some type of de facto barrier to refugees’ labor market access.

Regionally, we find that Latin America has the strongest legal frameworks, while Europe has the strongest labor market environment for refugees in practice. Africa and the Middle East are in the middle, and South, Southeast, and East Asia score the lowest in both de jure and de facto measures.

On average, we find that high-income countries offer the strongest work rights for refugees in practice. However, high-income countries also more commonly restrict who qualifies as a refugee, impose significant restrictions on asylum seekers, or limit territorial access of would-be asylum seekers in practice.

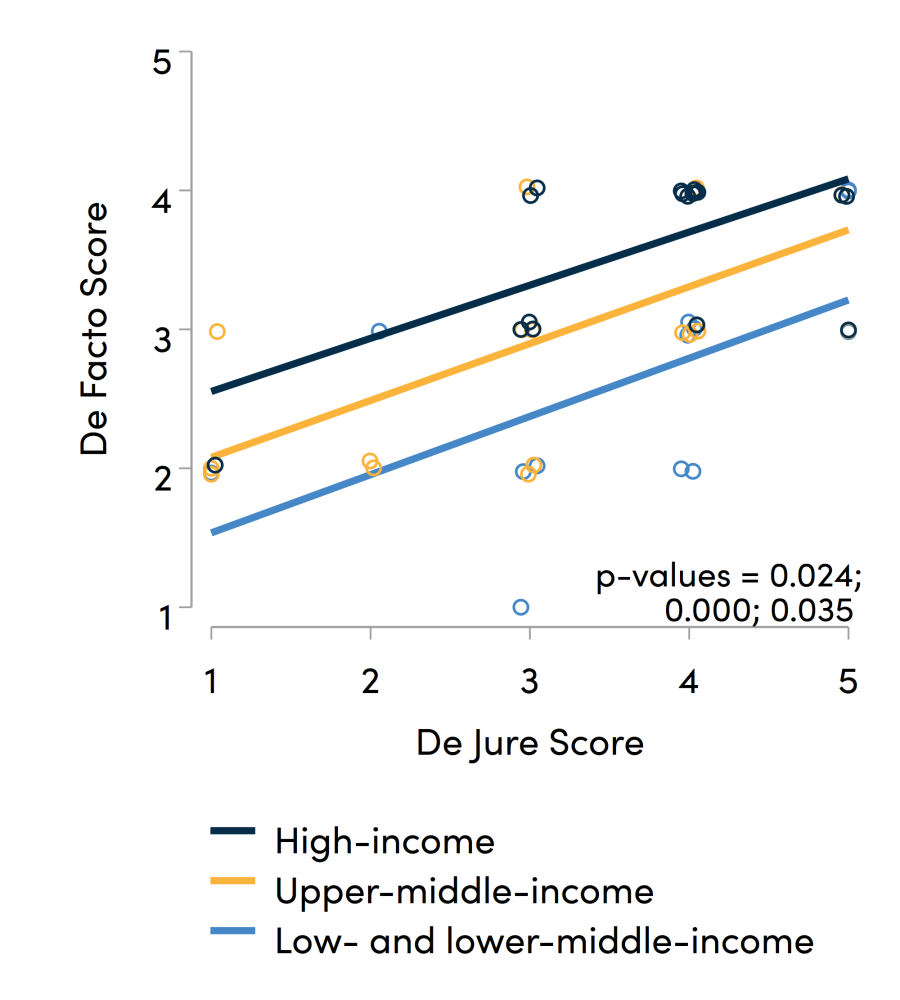

Finally, we find a larger gap between de jure and de facto scores in low-income countries than in high-income countries. But de jure and de facto scores are strongly correlated with each other, including within income groups. While the law is not enough to ensure refugees have work rights, it is often an important starting point.

Figure 4. The close correlation between de facto an de jure scores

The report also includes a discussion of the literature around refugees’ work rights, the agreements in international law, and the connection between work rights and other country characteristics. This is in addition to an analysis of other factors of economic inclusion like education, healthcare, degree validation, and financial services, all of which are documented for each of the 51 countries.

What’s next

This new global report, and its accompanying dataset, are part of an initiative led by CGD and Refugees International titled “Let Them Work”. For the past three years, we have conducted research to better understand important questions around refugees’ labor market access. From Peru to Ethiopia, we have documented the barriers and potential gains from refugees’ economic inclusion. Others’ research continues to demonstrate these benefits, including through increased productivity (Altındag et al., 2018), tax revenues (Evans and Fitzgerald, 2017), or GDP growth (Clemens, 2022).

Beyond country-specific conditions, there are two main sets of actors who can enact systemic change to expand refugees’ work rights globally: refugee-hosting countries and donors. Thus, in the 2022 Global Refugee Work Rights report, we put forth a number of recommendations for systemic change.

Refugee-hosting countries should:

-

Ensure their laws grant refugees the right to work and move, as our data and experience suggest that laws are an important foundation for the environment in practice, and then follow through in implementation.

-

Automatically include the right to work and freedom of movement as part of refugee status. In addition, these rights should be clearly stated in documentation, as respondents often noted confusion among employers around whether hiring refugees was legal.

-

Include refugees as constituents in work rights policymaking and accountability mechanisms.

Donors should:

-

Incentivize host governments to expand refugees’ right to work. The World Bank’s IDA19 Window for Refugees and Host Communities includes a framework to document recipients’ progress on refugees’ work rights. This mechanism should be strengthened and expanded.

-

Strengthen accountability mechanisms for Global Refugee Forum pledges. The Global Compact on Refugees includes a pledging mechanism used to assess progress on solutions for refugees. Donors should invest in strengthening this, for example by developing a more robust and widely-accepted assessment mechanism.

-

Provide support to host communities in addition to refugees. Financial support can mitigate any negative economic effects of refugees on host communities and increase hosts’ support for refugees’ labor market access, especially when hosts know the assistance is coming through the refugee response.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.