Recommended

When a policymaker or donor partner (a “decision maker” for the purposes of this post) poses a policy question—“What’s the best evidence to retain health workers in rural clinics?” “How can we scale an agricultural extension program effectively?” “Was that program to root out school violence successful?”—-you may do some analysis to figure out the answer. But what’s the best way to share the results of that analysis?

Researchers at think tanks (and at many other organizations) often face a dilemma: invest time to write a scholarly paper or do a quicker piece of policy writing (e.g., op-eds, blog posts, social media, direct emails to decision makers or their advisors). There are pluses and minuses to each of these types of writing (Table 1). There are also interactions between the two: scholarly writing lends credibility to policy writing, and policy writing can lead more people to discover your academic writing.

Table 1: Pluses and Minuses of Scholarly vs Policy Writing

| Scholarly papers (for publication in academic journals) |

Policy writing (op-eds, blog posts, social media, direct email) |

|---|---|

|

|

(Rachel Glennerster has written insightfully about academic vs policy jobs for economists; there is some overlap.)

How to decide what kind of product

When decision makers write to me with questions (or I see a question come up in policy discussions or I just really think someone should be thinking about a particular question), I have to decide whether this is a quick email to a decision maker, a scholarly paper, or something in between.

While you might write a blog post without a paper (since getting a paper published takes much more time), I think it’s exceedingly rare that it makes sense to write a paper and not disseminate it. I almost never write a paper without accompanying it with a blog post, a Twitter thread, a post on LinkedIn, a post on Facebook, etc. The blog post can usually be done in a couple of hours. The social media posts needn’t take more than a few minutes each. Sometimes they deliver high returns in terms of visibility; other times they don’t. But the cost is quite low, so the expected return makes it cost-effective.

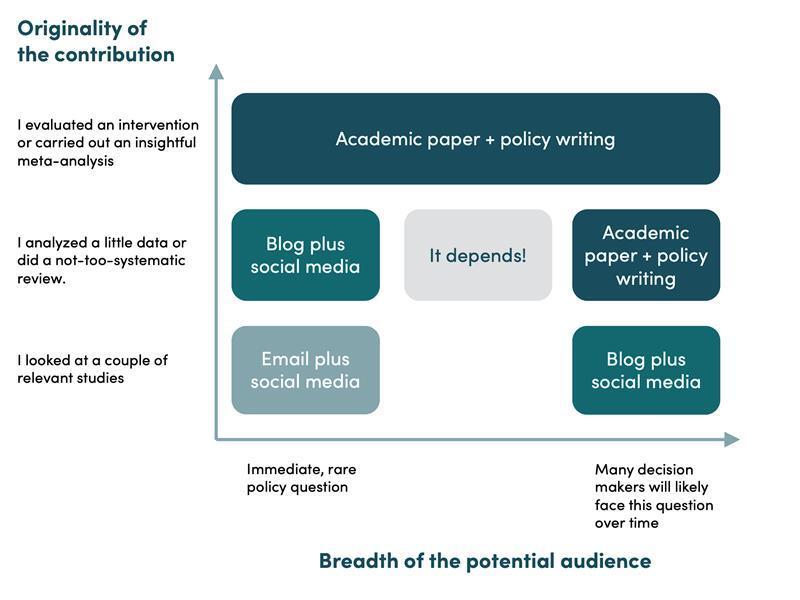

The decision largely depends on two questions: (a) how general interest is the question? and (b) how original is my contribution? The interaction between these two largely affects which type of writing and what kind of outlet I choose (Figure 1).

The more original my contribution, the more likely I am to try and publish a paper. This one is likely obvious: it’s worth getting original contributions into the scientific literature so that other research (and policy) can build on them.

At the same time, the more general interest the question is (i.e., the more people I think are likely to be interested in the answer, especially if I think people will be asking the question repeatedly over time), the more likely I am to try and publish a paper. Of course you should also publish a blog or an op-ed (as always), since there’s a general audience. But at the same time, if some version of the question is likely to come up again and again, then having a paper (with all the documentation that entails) means you can easily write a new blog based on the old paper when the same policy question rears its head again.

Figure 1: What Kind of Output Should I Produce? It Depends!

Let me give a few examples.

Narrow audience: If the question is extremely narrow and time-specific (e.g., someone at USAID asks, “Should we make this policy change?”), then an email might be the most you’ll get out of it. (But that email may have great impact!) On the other hand, it’s always useful to think: Are there other people who will face similar decisions, for which the thinking and analysis I’ve done on this would be useful?

Low originality + broad audience: Recently a practitioner asked me, “Can you tell me anything about how to do cost-effectiveness analysis for a school feeding program?” There are already a lot of templates and guidance out there on cost-effectiveness, so it didn’t make sense for me to write a paper on it. (Well, Anna Popova and I did write one, but that was a few years ago.) So instead, I just brought together resources and shared them by email with the petitioner. But I thought the audience was larger than just him, so I spent an extra hour and turned the email into a blog post. Then I took an extra ten minutes and shared the blog post on a variety of social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn).

Medium originality + medium breadth of audience: When we just do some very simple empirical analysis, it can often go in either a blog post or an article. (It depends!) During the Ebola epidemic, Markus Goldstein and Anna Popova and I thought more people should be thinking about the likely longer term impact of high health worker mortality in countries that already had relatively few health workers. So we did some simple analysis and were able to publish it quite quickly. Even though that particular Ebola epidemic is past, the paper continues to be referenced in new research.

Another time, when Tanzania was under pressure to roll back its ban on adolescent girls returning to school after childbirth, Amina Mendez Acosta and I did some simple analysis and tried to publish it quickly, but the process took long enough that the work didn’t come out until after that particular round of the debate was over. (The analysis did come out later, and the debate did resurface.)

Medium originality + broad audience: Another time, a researcher asked me, “What’s the best way to measure student absence from school?” I poked around and couldn’t find any guidance on it—there’s lots of guidance on measuring teacher absenteeism—so Amina Mendez Acosta and I pulled together all the evidence we could find on how to do this and wrote a short paper. We didn’t do original analysis, but we brought together lots of comparisons from existing papers. (That modest contribution is on its second round of revisions at a journal, which does indicate the added cost of seeking to publish this as a paper relative to just putting out a blog.)

High originality: If I’ve done some significant original research—either an evaluation or a meta-analysis—then my inclination is to try and get it into the scientific record through article publication, even if I think the audience is relatively narrow, in part because it’s hard to predict when questions will come up again.

Other considerations

Sometimes the timing of the policy question can affect the order of products rather than the choice of products. For example, when colleagues and I learned that decision makers at an organization were questioning whether the risks of violence at school were so great that they should weaken their support for universal secondary education, we did some analysis and shared it directly with decision makers by email. Then, we thought the contribution was original enough and the question would like resurface, so we published it in a journal.

Sometimes researchers may think “could I even publish this as a paper?” Even economists who principally publish outside of the very top journals may be influenced by the make-up of those journals in terms of what is publishable. In fact, many types of analysis are publishable in what I consider to be respectable journals. To give a sense of the breadth, in addition to experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations or systematic reviews, I’ve published papers—almost always with co-authors—providing practical guidance (on measuring maternal mental health, on carrying out phone-based assessments, on improving the ethical implementation of randomized controlled trials), characterizing current levels of trends (in girls’ education, on teacher pay in African countries, on the size of effects in education studies, on the quality of health care provision in African countries).

Of course, there are other factors. Here are a few:

- Your incentives. If you’re a pre-tenure academic, then your professional incentives may be entirely focused on research that can be published as academic papers in highly ranked journals. I still think, once you write those papers, it’s worth writing a blog post and sharing it on social media.

Outside of academia, the pressure may be on the other side, to focus on policy writing or just on getting working papers out. But I’d propose that if your training is in scholarly research, there is value in continuing to nudge scholarly papers out the door to retain both the credibility that brings and the detail-oriented thinking it forces. You may not have time for a lot of this, but in my experience, consistency is more important than volume. (I try to consistently have papers out under review; just nudging them out the door.)

- Your access to policymakers. If you have particularly close access to a decision maker for a time, then you may focus more of your energy on policy writing and less on scholarly writing.

- Your tastes. I tend to always think, “Could this be a useful published paper?” And then I work backward from there. This strategy can mean lots of papers, but it also means not only less policy writing but also less time dedicated to a few, weightier scholarly papers. I have colleagues who regularly publish analysis in blog posts that I would submit to a journal. Some of this is career incentives, but some of it is taste.

Takeaways

There is great value in using empirical analysis to help decision makers improve policy and programs, and to that end, there is value in both scholarly writing and policy writing. Time is limited, and needs are many. But the originality of the contribution and the breadth of the challenge are two factors that can help to decide how best to use your time to improve your corner of the world.

Thanks to Ranil Dissanayake and Maya Verber for improving this blog post.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock