On the first sub-Saharan trip for a UK Prime Minister in five years, Theresa May deserves credit not only for championing the importance of global cooperation but also for a speech which potentially has the key ingredients of an inspiring new Africa-UK development partnership with both “a radical expansion of the UK’s presence in Africa” and a commitment “to use all of the levers of Government to drive development.”

But will she turn the rhetoric into reality? Mrs May is not the first UK Prime Minister to declare the beginning of a new partnership with Africa. Tony Blair said something similar but his ideas never became reality and, in the last decade, Africa-UK economic progress has been virtually stagnant. Despite its aid commitment, the UK is also lagging well behind France as a development leader and can also learn from China.

When the PM returns to London, her vision may be crowded out by the challenge of delivering a successful Brexit. Mrs May has a reputation for thinking carefully before committing to an approach, and then doggedly seeing it through. She’ll need every bit of that persistence if she’s to succeed—but if she does, her speech in Cape Town will mark the most significant change of UK policy toward Africa since Harold Macmillan gave his Wind of Change speech, also in Cape Town in 1960.

In this blog, we look at the Prime Minister’s new partnership, compare it with the approach of France, China, and the EU, and make three recommendations to turn it into reality.

A new Africa-UK Partnership?

The Prime Minister made a number of announcements on her first visit to Africa as Prime Minister. She emphasised again that the UK would continue to champion global cooperation and the international rule of law. Her most eye-catching message was to make the UK the top investor in Africa by 2022 and to “create a new partnership between the UK and our friends in Africa, one built around our shared prosperity and shared security."

One concrete new element is that the UK will increase the amount of aid that goes to Africa, in particular through CDC Group (the UK institution which finances companies to operate in poor countries) to stimulate private investment. Last year, CDC invested nearly £500m in Africa, and the PM’s new £3.5bn commitment over the next four years implies a yearly average of £875m, a 75% increase.

But the PM also made clear that the UK plans to “bring so much more to the table than just government funding” and that:

a driving focus of our development programme will be to ensure that governments in Africa have the environment, knowledge, institutions and support to attract sustainable, long-term investments in the future of Africa and Africans.

In concluding her speech, the PM not only committed personally and for the long-term, but also addressed the critical weakness in the UK’s current approach—the lack of a multi-dimensional approach:

But I am… committed to using every lever of the British government to support the partnerships and ideas that will bring benefits for generations to come.

But is this vision an old one?

The Prime Minister will no doubt be aware that her speech echoes similar promises made by Tony Blair. In 2002 he visited four countries in west Africa and “hailed a new era of partnership between African nations and the West.”

This partnership was formalised under the G8’s Africa Action Plan, adopted later that year, which aimed to spur the continent’s development via a multi-dimensional approach that included aid, debt relief, the promotion of trade and capital flows, investment in infrastructure and social sectors, and peacekeeping and security. The Action Plan promised bold international engagement and coordination to end Africa’s “crisis,” with the UK playing a leading role. Yet few remember the UK’s partnership now, despite the personal commitment of the then-Prime Minister and Chancellor.

UK third-bottom of G7 trade with Africa

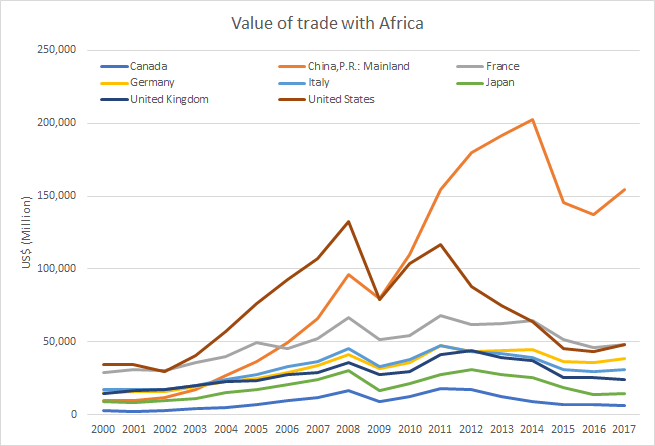

Despite Tony Blair’s aspirations of British leadership, the UK’s progress has stalled—the UK’s investment level is one of the highest but is largely unchanged since 2011, and trade with the continent is now lagging behind the other G7 countries and is less than one-sixth of China’s.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics, G7 countries plus China

Strong French Leadership

In terms of wider African influence, France’s Macron has visited eleven countries in nine trips since becoming President last May and has seven times the number of diplomats as the UK. France had over 14,000 troops in the region in 2016 (SIPRI data), compared to under 500 from the UK (UK Defense statistics).

The Prime Minister committed to “radically expand the UK government’s presence in Africa, opening new missions and bringing in trade experts, investment specialists, and other policy experts"—and clearly, the UK will need a substantial change of gear.

Lessons to learn

As the UK translates the promise of a new partnership into detailed policies, there is much that it can learn from others, especially China, France, and the EU. China’s vast Belt and Road Initiative aims to invest up to $8 trillion in developing countries’ infrastructure and productive capacity in order to promote international trade. The French-led “Sahel Alliance” is implementing over 500 projects in multiple sectors in the Sahel countries in order to “transform” the region by 2022. Meanwhile, the EU has promised elements of this approach in its External Investment Plan for Africa which combines blended finance, technical assistance, and policy dialogue in order to stimulate private investment on the continent.

The key lesson for the UK to draw from these approaches is the need for an integrated strategy for development. This would mean tackling security, investment, and infrastructure in a targeted and coordinated way. With Brexit, the UK will have more control of additional policy instruments like trade, migration, investment policy, and regulation so that it can use a wider range of measures and tailor its development policy to the need of the partner. But if all it means is that we will keep existing trade access arrangements and increase investment without a fully joined up and coherent approach, then the initiative will be looked back on with the same lack of enthusiasm as its many predecessors.

From rhetoric to reality

How can the PM achieve the change of gear she needs? These three actions can help deliver her vision:

-

First, on using every lever, the UK should identify where its policies can support development across all the tools at its disposal—trade, grants, diplomacy, security, R&D, tax, technical support, VISAs, patents, finance, and reform of international systems. This work will need to be undertaken across government—by Ministers and departments—and should be ambitious and about meaningful policy change.

-

Second, integrate and tailor: the UK needs to understand how these proposals translate into a coherent, integrated plan for its development partners. It can build on DFID’s country-by-country economic diagnostics that fed into its economic development strategy. Similar diagnostics are used by the IMF and World Bank, but their instruments are limited to finance. These assessments should be co-developed with the partner country, consulted on, published, and be used to integrate and tailor the UK's approach.

-

Third, personal leadership: the Prime Minister will need to show personal leadership—holding her Ministers to account, understanding African leaders’ challenges, forging personal relationships, sustaining engagement, and ensuring these actions happen rather than allowing departments to attempt the window-dressing so familiar in response to initiatives led from No10.

Using every policy lever

For the UK’s development partners, this approach would make the UK an intelligent, influential, and consistent partner. Mrs May recognises that going beyond funding is what would mark out the UK’s development programme, and that every policy lever is needed.

The Prime Minister has shown courage in defending global cooperation, and a vision in her commitment to a new partnership with Africa. But we have heard these words before—the question is whether will we now see the action across government to make it a reality.

We’ve very grateful for advice from Owen Barder on earlier drafts of this blog, and for input from Anita Käppeli and Lee Robinson. All views and any mistakes remain those of the authors.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Social media image by GCIS