Readers of The Economist were treated to a tantalizing prospect this past week: the possibility of eradicating malaria in the developing world (also featured in The Lancet). The piece presents this hope based on the prospect of developing a malaria vaccine, and the recent proposal of the biggest health program funder in the world - Bill Gates.

If a vaccine were indeed close to development, such a prospect would seem feasible. But a generally agreed-upon timeline, given by the global Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap, has the goal of developing a vaccine by 2025. The eradication initiatives are expected to precede this development. What would be involved: massive roll out of access to effective treatment; scaling up of indoor-residual spraying and substantially increasing use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) in endemic areas.

Steven Phillips is the Chief Medical Officer for Exxon Mobil, a company whose African operations necessitate significant efforts to contain malaria to protect their workforce. The Economist article has him expressing profound skepticism about the possibility of eradication, calling it "technically impossible." He notes for example that vaccines can't do much good if they don't reach endemic villages. Similarly, ITNs that are not distributed or not used don't work, and neither does DDT that is not sprayed on household walls. ACTs likewise don't work - unless used. The problems with getting these interventions delivered are legion, and were a major contributor to the poor performance of the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) initiative, as described in an external evaluation.

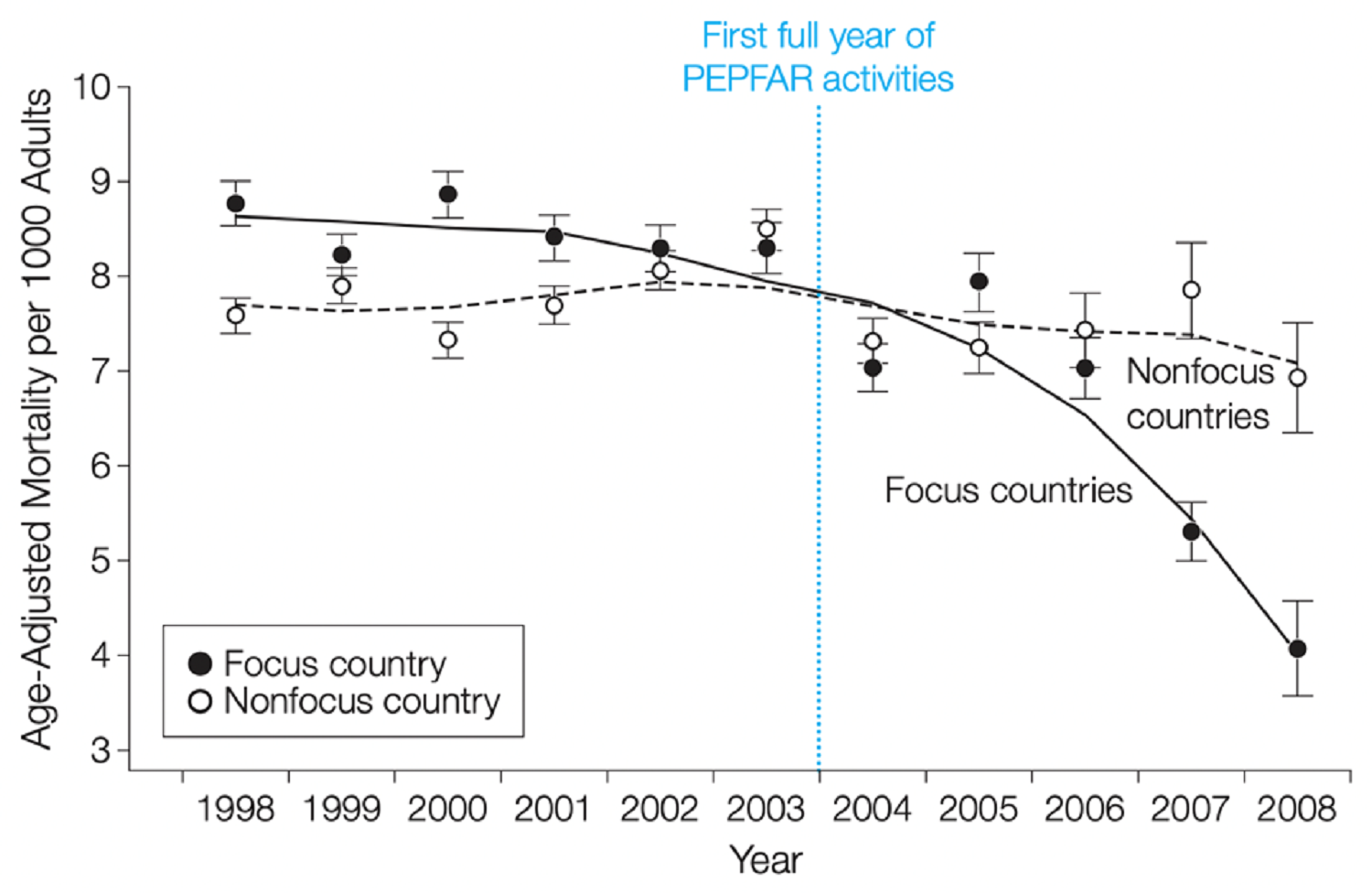

The Economist points to a recent UNICEF report as containing evidence that the biggest problem - that of getting the interventions delivered - has been overcome (see figure 1 below and page 2 of the UNICEF report). Indeed, the words in the report are encouraging. But a closer read, focusing on the data presented, is far more sobering. Despite all the attention and added resources since RBM was launched nine years ago, the burden of malaria has increased. And while some countries, as seen in the graph below, have achieved significant increases coverage of bed nets, very few are on target to meet the program targets. Eradication would require much higher rates of coverage of all three key interventions: ACTs, ITNs, and IRS - a feat not yet achieved nation-wide in a single endemic country.

The recent encouraging experiences referred to in the report related to ITN procurement, or the commitment to buy and distribute ACTs at subsidized prices. The actual delivery of these interventions is yet to be observed or measured. But hopes are high. Given the experience to date, in fact, one has to ask if expectations are too high.

Does it matter if the global health community gets a bit too optimistic? Perhaps a dose of optimism, plus Gates cash, will give malaria programs just the shot in the arm (no pun intended) they so desperately need? I'm a fan of optimism - but there is a very real risk that it may lead to diminished attention to the serious, and not yet resolved, problems of how to get effective interventions delivered (not just developed or purchased). Surely, the first steps in the eradication effort must be to: 1) sort through what we do know, and don't, about how to get the "big three" interventions delivered; and 2) to find ways of ensuring that the key technical agencies and funders support programs based on that knowledge (see here for a related discussion of WHO's worrying departures from the technical consensus on effective ITN coverage programs). Raising the money and momentum is the easy part - now the real work begins.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.